Being lost or being a missing person

I’m lost!”

This sentence imposes itself suddenly, like a slap in the face. It’s verbalized only in thoughts or sometimes pronounced aloud, almost as if the person who speaks them is trying to seek their first point of reference in the sound of the words.

Anyone who’s lived through the experience of getting lost in the wilderness knows the violent cascade of emotions, physical reactions, thoughts, and mental images and worries that suddenly pours over the victim. The feelings are hard to imagine if you haven’t been in this situation.

Over time, researchers in the neuro-cognitive, psychological and statistical fields have studied in depth the psychology and behavior of people who are lost, getting at a classification of typical behavioral patterns that can help rescuers increase the chances of finding the missing.

WHAT DOES ‘BEING LOST’ MEAN?

Intuitively, we could say that the feeling of being lost lies in the difference between where you thought you were and where you really are. Much research has been done on the subject, and it can be more complicated than simply finding yourself well off the trail.

In his book, Lost Person Behavior, Dr. Kenneth Hill more precisely defines “being lost” as “the condition in which an individual is unable to determine his geographical position and has no means or method for reorienting himself.”

A research article by Lisa Jones-Christensen and Scott C. Hammond (2015) identifies five stages of the psychological condition of the person who is lost:

Separation. The subject realizes he’s no longer close to other people and doesn’t know how to reach them. At this stage, they still feel capable of reorienting by themselves; they’re convinced they’ll be able to find the other people.

Isolation. The subject begins to “feel lost,” losing the certainty of finding others and starting to think they’ll have to handle the situation by themselves.

Deviation. The person starts acting irrationally and unrealistically—prey to the unpleasant emotions they’re feeling—instead of trying to gather enough information to assess the situation. In this phase, the person can react by denying their condition. However, at the same time, they can act impulsively in an attempt to save themselves. For example, they might walk in a specific direction without being sure of their position, thus running the risk of losing their orientation even more.

Deprivation. In this phase, the emotional aspects take over, with an intense psychophysiological alarm, which translates into experiences of increasing anxiety (up to panic), with a progressive loss of lucidity, which can be followed by a disarming sense of despair. Moreover, thoughts of doom can easily impose themselves, and the individual is convinced that no one will come looking for them.

“Each passing of a human or animal through a natural setting results in identifiable changes to the environment. In practical terms, the soil and vegetation—and, in a different way, animal behavior—capture these changes as clues we can decipher.”

Realization. At this point, the missing person inevitably comes to terms with their condition and moves in two possible directions: if they bear the psychological pressure of the situation, they might stop, gather information and rationally think of a solution, believing that in one way or another, they’ll find their way back or be found by rescuers. On the other hand, the missing person can progressively lose confidence in their abilities and lose hope of being found.

MENTAL EFFECTS OF BEING LOST

It’s evident that the mental state of the missing individual and, in particular, their emotions, has an effect on their ability to manage the situation and on their choice of strategies to resolve it.

On the psychophysiological side, as early as 1908, Yerkes and Dodson had investigated the relationship between the level of activation of an organism and its psychophysical performance, developing a model of arousal curve that’s still valid today.

“Unlike other important skills such as fire-making, purifying water, building a shelter or foraging, the art of tracking actually provides you with the ability to solve the challenge of being lost.”

We define “arousal” as “a temporary state of excitation of the nervous system determined by a significant stimulus and characterized by an increased attentional-cognitive reactivity, which enables the subject to react more quickly and effectively to the demands of the environment.”

This state of activation involves both the central and peripheral nervous systems (somatic and autonomic), bringing the whole organism to the condition of being able to react to the environment request. However, research shows that the state of activation and performance are not correlated in a linear way but follow an “inverted U– ” trend.

This means that a low level of activation produces a low performance, with feelings of “emptiness,” tiredness and reduced reactivity to stimuli. As the activation increases, the performance increases, reaching a peak of optimal psychophysical performance; this is represented by the peak of the curve.

However, if the arousal increases further, unpleasant states of physical hyperactivation, feelings of anxiety, loss of lucidity, difficulty in concentrating, hyper-reactivity and emotional dyscontrol quickly take over. At this stage, the performance, instead of growing again, collapses in a very short time.

Hyper-arousal can generate a neurochemical cascade so intense that it results in a feeling of increasing fear—up to panic—in which the nervous system puts the entire organism in the “fight or flight” condition, directing the subject to immediate action and not mitigated by rational processing.

“Typically, [shame] shows up as one of the first emotions that the missing person feels after the initial phase of disorientation and the subsequent awareness of THEIR condition.”

This is typically the situation in which the missing person, supported by this kind of psychophysiological activation, starts irrationally running without a precise direction, thereby aggravating the disorientation, the risk of injury and possibly making it even harder for rescuers to find them.

A less “explosive” emotional reaction, more linked to individual personality traits, is shame, which can turn out to be unexpectedly risky if it’s not kept under control in emergency situations. Typically, it shows up as one of the first emotions that the missing person feels after the initial phase of disorientation and the subsequent awareness of their condition.

“What will my loved ones think of me?” “If they come looking for me, they will think I’m stupid” or “What does this make me look like to my friends?”

These kinds of thoughts can lead to irrational and dangerous behaviors, such as insisting on looking for the way back—despite being completely disoriented and not having adequate technical skills—or hiding from rescuers to avoid embarrassment and the feeling of being judged.

The categories of missing persons most at risk from this point of view are precisely those from whom one would expect a higher level of technical preparation and knowledge of the territory. This includes levels of knowledge and skills that are suitable for the outdoor activity during which they get lost. This can include people such as hunters, expert hikers, survival enthusiasts and even guides.

COMMON STRATEGIES OF THE LOST

Dr. Hill lists nine typical strategies people try while attempting to find their way back when they realize they are lost:

Random Traveling. The person is confused and moves randomly in the environment, simply following the lines of least resistance (vegetation, terrain or slope), with the sole aim of recognizing something familiar and reassuring.

“Anyone who’s lived through the experience of getting lost in the wilderness knows the violent cascade of emotions, physical reactions, thoughts, and mental images and worries that suddenly pours over the victim.”

Route Traveling. The person decides to follow a path, a track, a creek or any other element of the environment that seems to follow a specific direction. The subject neither knows the route nor where the path they’re following will lead but hopes that sooner or later, they’ll encounter something more familiar.

Direction Traveling. The subject is convinced that salvation is in a direction they selected according to some criteria they can justify to themselves. They therefore follow that direction, neglecting any paths, signs or other reference points, because they consider them to be misleading.

Route Sampling. The subject gets to a crossroads of different paths and then follows a path for a certain distance, going back each time to test them all.

Direction Sampling. This is similar to the previous strategy but, in this case, the lost person doesn’t have the advantage of starting from a crossing of paths and tries to verify different directions chosen arbitrarily, starting from an equally arbitrary point.

View Enhancing. The lost person tries to improve his perspective of the surrounding territory by climbing a peak, a ridge, tree or anything else that will improve their view of the area.

Backtracking. Once they get turned around, the person tries to follow their path backward, trying to recognize the elements of the environment that they passed as they were getting lost.

Using Folk Wisdom. This is an attempt to reorient oneself by referring to popular knowledge and rumors on how to find one’s way in the woods. Some examples are, “Streams always lead to inhabited areas”; “Moss always grows on the north side of trees”; and other similar phrases you’ve heard many times.

Stay Put. Realizing that they no longer know how to find the way, the person stays where they are in the belief that this will facilitate the rescue that will eventually be launched.

BEHAVIORS OF THOSE WHO GET LOST

Robert J. Koester, author of Lost Person Behavior, stated that individuals demonstrate a notable variety of responses to realizing they are lost.

Children (up to about 10 years of age) and the elderly (especially those with neurological conditions such as dementia or Alzheimer’s disease) are those who most likely lose orientation. Losing points of reference, even in confined or familiar environments, happens almost daily for them.

For other individuals, the simple awareness of being lost doesn’t always result in common-sense behaviors. While some cases result in decisions based on experience and logic that can lead to positive outcomes, the choices in others can turn out to be completely erroneous.

This happens due to the following factors:

- Stress, which causes their arousal level to be too high;

- The presence of physical injuries and/or emotional trauma;

- A sudden change of weather conditions, especially if they’re unprepared for the new situation;

- A lack of hydration;

- A lack of the right caloric intake;

- The presence of predators.

As Koester points out, individuals tend to respond to being lost by relying on their own experience, acquired knowledge and common sense.

Mountaineers, for example, have statistically demonstrated that reaching high-visibility areas makes it easier for the Alpine Rescue to identify and recover them, thanks also to their higher-visibility equipment. Alternatively, hunters often rely on reading animal tracks or trails to reach water sources, which might lead to inhabited areas.

The biggest problems occur among those who lack outdoor experience. The mere circumstance of getting lost causes anguish, often resulting in almost immediate panic—a prelude to potentially lethal decisions.

In reviewing countless cases of people who got lost on the Appalachian Trail, the most distinctive trait Koester identified is the tendency for hikers to proceed in an imaginary new trajectory. This turns out to be almost circular, often following the dominant hand. In some situations, they don’t even recognize the portions of the trail they’ve already encountered. Their persistence in finding the trail is so blind that they’re unable to remain lucid. Markers such as fallen trees, cliffs, gorges and so on become insignificant details in their eyes, because a clouded mind cannot focus on them.

ENEMIES OF THE LOST

The moments that immediately follow the awareness of being lost are undoubtedly the most critical.

While some people demonstrate self-control, calm, logical reasoning and the ability to react constructively, others become so overwhelmed that they develop fears relating to the environment.

Their anguish starts as aversion and can progress to terror toward everything around them—trees, terrain, wind and other noises and, of course, animal sounds.

Mastering terror can be difficult to accomplish. Nonetheless, you can make these elements your allies. Interpreting signs provides an indispensable aid for orientation, and concentrating on that task can help bring emotions under control, possibly enabling you to remedy the situation.

ALLIES OF THE PAST

Each passing of a human or animal through a natural setting results in identifiable changes to the environment. In practical terms, the soil and vegetation—and, in a different way, animal behavior—capture these changes as clues we can decipher.

Terrain. The ground often records traces left by people and animals. They can be signs of what passed and when, which can be very helpful to know. Soft dirt and clay, mud, sand and snow-covered surfaces constitute excellent substrates for footprints and for their conservation over time.

Vegetation. Bent branches, leaves and flower petals on the ground, and torn moss are some clues the environment provides us about the presence of a somewhat recent passage.

Animal Behavior. The sudden flight of birds—an indicator of danger—is one of the most common animal behaviors we can observe, even in an urban or suburban environment. Likewise, increased insect activity signals a change in weather conditions.

THE ROLE OF KNOWLEDGE

Knowing how to read and interpret footprints and other signs is not the privilege of a few. Rather, it’s an ancient art that can be learned and practiced by anyone. (Editor’s note: Learn more about tracking by reading this author’s articles in the August 2020 [Volume 9, Issue 8] and the June 2021 [Volume 10, Issue 6]) issues of American Survival Guide.)

If applied to an emergency situation, tracking can prove to be a fundamental tool for—

- Backtracking yourself to make your way to a safe place;

- Understanding if a trail has been overlooked;

- Identifying the correct direction to go at a crossroads;

- Locating a safe area to spend the night in an emergency.

Unlike other important skills such as fire-making, purifying water, building a shelter or foraging, the art of tracking actually provides you with the ability to solve the challenge of being lost.

The Authors

Dr. Simone Bertossi is a psychologist and psychotherapist with more than 20 years of clinical experience working in various healthcare/mental health settings, including organizational mental health consultancy. He collaborates with the Italian Red Cross as an emergency psychologist and trainer.

Dr. Bertossi is a survival expert who has experience with extreme expeditions in different environments around the world—from the boreal forests to the Himalayas, the African savanna and jungle.

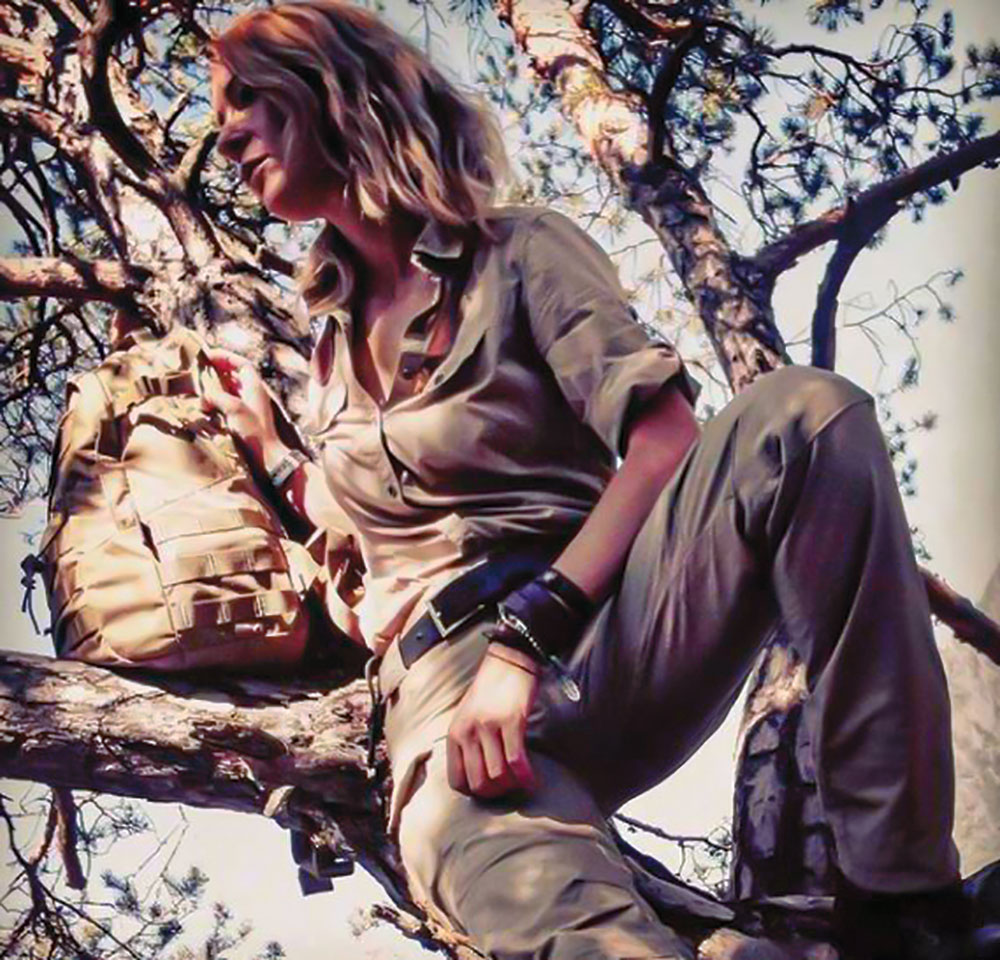

Kyt Lyn Walker has studied and taught the art of tracking for many years. She’s a passionate student and instructor of the discipline and is the man-tracking instructor for Hull’s Tracking School (in the United States) and the Centro de Formaccion Carcayu (in Spain). She’s taught members of numerous military and public safety organizations, as well as many civilians. She’s also a conservation ranger, certified by Conservation Rangers Operations Worldwide (C.R.O.W.).

Walken is also the author of several field guides and books and a frequent contributor to American Outdoor Guide.

The Story of Matthew Matheny

It’s August 9, 2018. Matthew Matheny, aged 40, borrows a friend’s car on his way to Mount St. Helens. The eerie volcano, located in the state of Washington, had erupted in a massive way between March 20 and May 18, 1980, causing a great deal of carnage, not to mention a huge stir in the media.

Thinking it must be an easy hike, Matheny wears a T-shirt, shorts and flip-flops. His destination is the Blue Lake Trail, as he tells his friend. Yet Matheny will only be found six days later … somewhere else.

What went wrong with Matheny’s intentions? To start, his lack of knowledge of the area. He later explained to the media that he wasn’t familiar with Mount St. Helens. He didn’t have a detailed map with him, nor did he have a compass or GPS.

The Blue Lake Trail appears to be a harmless path, devoid of challenging gradients. Furthermore, the panorama is certainly remarkable, because majestic Douglas fir pine trees form the natural setting for the lake Matheny intended to reach.

He started his hike by following the trail signs—until the unexpected took over. The path became increasingly narrow, almost nonexistent. He noted that the area he traveled through (rough and almost rocky) was strewn with the remains of the 1980 volcanic eruption.

Without any reference point, Matheny lost his balance at a particularly steep point. Tumbling down, his flip-flops broke, forcing him to continue with bare feet. Shortly after that, his phone’s battery died.

Alerted by Matheny’s parents, the local search-and-rescue group quickly set out on his trail, deploying 30 rescuers, several search dogs, a drone and helicopters. They continued the search for six days … without success.

Meanwhile, the only solution Matheny saw was to keep walking. He walked for hours, dehydrated and almost exhausted. His hope of surviving was driven by previous knowledge that went back to his time as a Boy Scout. This allowed him to recognize some edible berries as he continued on.

After regaining a degree of hydration from the berries, but still hungry, Matheny later explained that he killed and ate bees that had been attacking him as he moved through the woods.

Rescuers tracked him down after almost a week. He was dehydrated but “not in such bad shape,” according to a rescuer.

The simple decision to carry a detailed local map or GPS would have prevented almost a week of discomfort and anxiety for him, his family and friends and would have prevented the need to launch the large search-and-rescue mission.

A version of this article first appeared in the November 2021 issue of American Outdoor Guide Boundless.