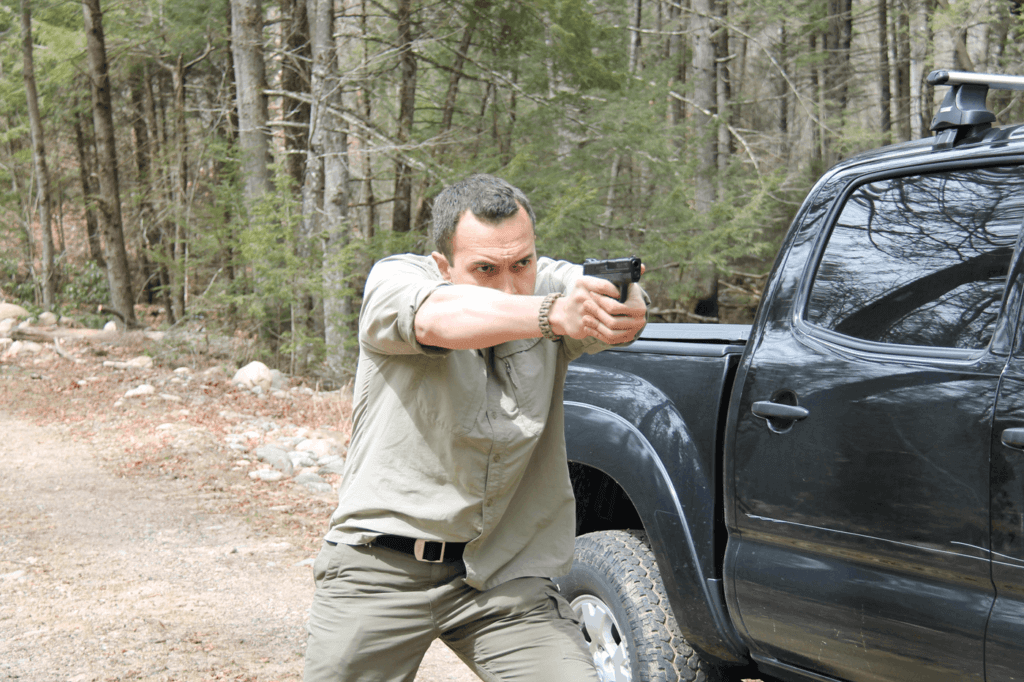

These commands were barked at me during the Warrior 1.0 pistol course with the Sayoc Tactical Group. After a course of fire, we students were told to assess our surroundings. If we thought it was safe, we could holster our weapons and proceed accordingly.

This series of actions was repeated throughout the weekend and students quickly learned to Observe, Orient, Decide and Act (O.O.D.A.), and then repeat (loop). We learned to quickly repeat the cycle and to be ready to move at a moment’s notice, because another threat could present itself. It is with this training experience I came to a realization: There are different survival-thinking formulas, and there is also the potential for conflict between these viewpoints on self-preservation problem solving.

At the very beginning of most survival manuals is a section on survival psychology. This is generally overlooked and skipped in favor of the gear and skills subsections. Survival psychology is a skill but more often than not, the S.T.O.P. protocol is the one most frequently cited. S.T.O.P. (Stay put, Think, Observe, Plan) has been widely used in the outdoors community and is accepted as the universally correct traditional course of action. Aside from this and for those in law enforcement, military or self-defense circles, the O.O.D.A. loop is a similar mindset. It relates to the split-second decision-making necessary for tactical advantage and survival. I’ve been thinking about the importance of each and now have a new perspective of how and why each should be taught.

THE WORLD WE LIVE IN

We live in a changing world with many new threats to our existence. The demands of the 21st century are far greater than those of the 20th. Our awareness, preparation and action must change accordingly with the times. For years, I taught the S.T.O.P. protocol in wilderness survival courses. For many wilderness emergencies stemming from getting lost or self-caused emergencies, the first step to “Stay put” or “Stop action” worked well to prevent further problems. Yet, there are some emergencies which are not your fault and staying put, standing still or rooting in place will cause more harm than good.

Consider recent terrorist events, mall attacks, school massacres or natural threats that strike almost without warning, like tornadoes or avalanches. Consider events on a smaller scale like avoiding a car accident, rendering first-aid to someone near critical status or responding to a violent argument at a busy intersection correctly. In these circumstances, stopping or even slowing down your actions are not necessarily the correct actions and thinking on the move to avoid danger is a better course of action. This is why I have changed my survival philosophy curriculum to teaching students to default to the O.O.D.A. loop mentality. Since mindset and training are closely linked, and training should be linked to realistic threat assessment (you wouldn’t learn South Pacific plants if you never plan to leave Nebraska), mindset should be linked to realistic threat assessment, too.

O-BSERVE YOUR SURROUNDINGS

O-RIENT YOURSELF TO YOUR ENVIRONMENT

D-ECIDE WHAT TO DO

A-CT ON YOUR DECISION

S-TAY PUT

T-HINK ABOUT YOUR SITUATION

O-BSERVE YOUR SURROUNDINGS & PREPAREDNESS

P-LAN

WHAT IS YOUR REALITY?

Added to my realistic threat assessment approach is the idea of time, place and manner. Assuming the average person spends one day a week in the outdoors (52 days total), he or she is still spending more time in a non-outdoor setting.

For the sake of argument, assume the non-outdoors setting is suburban or urban. Assume it is the time we spend at work, in the car or at home. We tend to carry unrealistic items on us for improbable emergencies. I carry a fire steel even in the city when the chances of me needing to use it for fire or signaling are highly unlikely. Why, then, should we adopt a mindset, like S.T.O.P., that will help us only sometimes? I also carry items in my daily carry bag that includes extra batteries for my flashlight, disposable respiration masks, work gloves and a multi-tool. I’m more likely to need these items in an urban/suburban setting. A perfect example of realistic preparation is the average hotel stay on vacation. I make sure to keep a flashlight near my nightstand, closed-toe shoes by the edge of my bed and valuables/sensitive documents in a small, easily portable bag in case I need to evacuate the room in the middle of the night because of a fire or natural disaster. If my gear is carried to address realistic threats, my mindset should follow suit as well. I haven’t abandoned S.T.O.P., it is still in my toolkit. It just isn’t used unless there is no urgency to start or keep moving.

TRUST YOUR GUT

Consider the importance of your gut feeling and how quickly you sense a threat. There are times when, in the process of threat discrimination, you don’t need to think about the possibility of danger because you feel your inner alarm sounding already. An excellent extension of this thought is found in the book I highly recommend, “The Gift of Fear” by Gavin De Becker. We have thousands of years of instinct built into our nature, yet we try to find logic and scientific order/explanation in our lives. The average person doesn’t listen to their instincts.

Consider too, the countless stories of police officers and military personnel who had a gut feeling, relied on it and lived to tell the tale. Regular occupational exposure to risk helps certain individuals develop a sixth sense. This hair-raising sensation is a natural indicator of urgency in a given situation. There are some everyman situations where it is possible to think about the feeling you have (passing someone suspicious on a trail or reassessing your interest in taking a van ride on a paddling trip if the driver is acting funny) and use a logical order of questions to come to a conclusion. Other times, there may not be the chance to think and you must simply act on your gut instincts.

IT CAN HAPPEN TO YOU

A perfect example of when the O.O.D.A. loop can be applied to the everyman is when we encounter a car breakdown. Imagine the worst neighborhood you know of. Would you want to walk around it looking for help or would you want to stay by your car and call from there? Maybe, you want to walk away from this neighborhood before nightfall and go back to your car the next day. As an instructor, it is hard to prepare the average person for reality when genuine stress will determine their action.

Is it possible to quickly choose which process to follow under stress? I don’t believe the average person can, and this is why I say “think movement” and “observe.” Considering the average person is in the urban/suburban environment more, it makes sense they should move away from danger then stop/think/observe and plan what to do next. Should one be used as a default? I think both should be used but in the order I just described. Movement means life. I cringe at the idea of those who freeze in the face of danger. When the fight or flight instinct kicks in, they simply freeze. The average person can improve their response and ultimately improve your survivability by practicing worse-case scenarios. Introduce stress through training modifiers and become inoculated to it.

SURVIVE, WIN, LOSE OR DRAW?

My law enforcement friends say to win in a gunfight or battle, “you must be faster than your opponent and be inside his O.O.D.A. loop.” The average person can adopt this same concept to larger more dangerous threats. Process threats faster than they can reach you and you will survive. See financial difficulties ahead and act accordingly. See emotional problems in your relationships and work to fix them. Anticipate problems with your vehicles and maintain them regularly. Always scan everything around you and don’t become complacent.

The decision to act may involve lethal force. Train harder than you anticipate fighting. You can never practice enough drawing from concealment.

How aware are you? Do you remember the last photo printed on the previous page or perhaps the color of the letters on the front of this magazine? Children are likely to play memory games like Go Fish but what can adults do? There are many options that may help build observation and memory skills.

Next time you visit a diner, pull out a pen and jot some notes on a napkin. Draw a map of the restaurant based on your memory. Populate the seating arrangement without looking up and from memory. See if you can pick up where the men, women, children, most physically able, most suspicious and possible concealed carriers are sitting. This drill will help you identify ways to profile people and categorize them into appropriate types.

On your next trip to the great outdoors, let your outdoor training partner unpack his/her bag in front of you. Offer to repack it for them. If they are a regular outdoorsman, they will likely have a system of organization. Do you recognize the pattern? Do you know where he/she likes to keep certain items? They will know if you are correct and they will let you know if you’re off.

You need not even leave your house to train your memory. Using this magazine, ask yourself the following questions. What was the last photo on the previous page? How many articles have appeared so far? What was the last advertisement? Keep track of your surroundings and your observations. It will improve your memory and your chances of survival.

Editor’s note: A version of this article first appeared in the How To special issue of American Survival Guide.