You’re visiting the beach, walking in the sand, taking in the salty air as the wind beats the waves. And as the undulating waves lap at your feet, you notice the familiar fronds in the sand and the multi-colored leafy structures on the rocks. You pick one up. It’s a bit slimy, sticky, smelly. You give it a more careful sniff. It’s actually a refreshing odor, reminiscent of the sea.

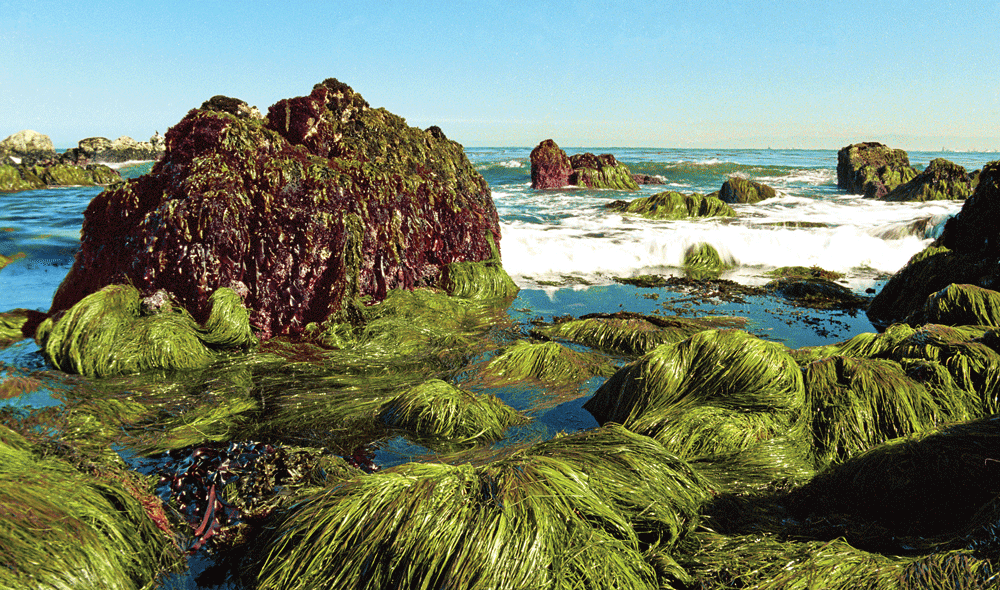

You’ve discovered seaweeds. Most people know seaweeds when they see them at the beach, whether they are floating in the surf, lying on the beach in piles, or growing all over the rocks. They grow in a large array of colors, sizes and shapes. The kelps are perhaps the most conspicuous along the west coast, with their long stipes and characteristic fronds. They often lie in masses on the beach. And the farther north one goes, the greater the diversity.

In general, the seaweeds have leaflike fronds, stipes that resemble the stems of terrestrial plants, and holdfasts that resemble roots. Some seaweeds are very delicate, and others are very tough and almost leathery. Many have hollow sections — “floats” — that allow them to float more readily. Others are like thin sheets of wet plastic, such as the sea lettuce.

Brown Algae

The color, which ranges from brown to muddy yellow, comes from the pigment fucoxanthin. Although this group includes some small, almost microscopic members, larger seaweeds with leathery textures predominate. The variety of shapes ranges from several-hundred-feet-long kelps, to whip-like fronds, to leaf-like structures of one to three feet in diameter.

All large brown algae (this includes several genera of kelp, plus rockweed, and sargassum) anchor themselves to rocks. This anchoring is accomplished by means of holdfasts, which are structures similar in appearance to roots of land plants. Their tough outer layer renders them relatively immune to being rubbed by fish and to the beating they receive when they’re broken off and washed ashore. They’re held upright by hundreds of air bladders. There are approximately 1,000 species of brown algae worldwide.

Red Algae

On the whole, the red algae are smaller than the browns. They’re also more delicately shaped, often appearing as graceful, branching ferns in hues ranging from violet, to red, to purple, to pink. Some are lance shaped with wrinkly margins; others have wide elastic fronds, and look like sheer sheets of plastic with ruffled margins. Some grow as thin filaments or leaf-like structures. The reds include the well-known Irish moss (Chondrus crispus), laver (Porphyra spp.), and dulse (Rhodymenia palmata). There are approximately 2,500 species of red algae.

Green Algae

These also grow as filaments or branching fronds. The most commonly eaten seaweed in this group is sea lettuce (Ulva lactuca), which actually looks like a thin sheet of lettuce attached to a rock. Though most green algae are found in fresh water, there are approximately 5,000 species of marine green algae.

Eating Seaweed

Seaweeds are not only very tasty (when prepared properly), but they are also very nutritious. They are probably the closest thing you can come to a “fast food” when you’re in the wild.

In general, seaweeds can be used as foods, food seasoning, medicine and nutritional supplement, and other utilitarian uses.

When I was originally researching seaweeds in the 1970s as a journalist and student botanist, I interviewed botanists, marine biologists, and seaweed specialists. Some believed that all seaweeds — all of the nearly 10,000 macroscopic varieties — are a completely nontoxic group of plants, and most agreed that these are safe to consume. The more conservative viewpoint suggested that one should take the time to learn each individual seaweed you intend to eat. This viewpoint had to do with the fact that there are so many seaweeds, and not all have been studied enough to make such a blanket statement.

Nevertheless, seaweeds are regarded as highly nutritious and generally edible, and we know of no toxic seaweed, assuming you follow our guidelines listed below.

Cautions

Some seaweeds are unpalatable due to their rubbery texture, and rigid structure, which can usually be overcome by drying and powdering or by various cooking methods. What works for one seaweed may not work for another. Where possible, talk to the local people who use seaweeds. Only by experience will you be able to learn which seaweeds are more palatable than others. As you experiment, don’t rely only on your taste buds’ first reaction—try ingenious ways of using seaweeds. Here are some of the commonsense precautions you should take if you’re going to try eating seaweeds: Never eat any seaweed that has been sitting on the beach, rotting and attracting flies. Seaweed that has already begun to decompose contains bacteria that will cause sickness if eaten. Be sure to thoroughly wash your seaweed before consumption. This eliminates any adhering sand and potentially harmful substances. A suggested method, especially if the purity of the ocean water is questionable, is to wash the seaweed in your bathtub or sink. First wash in hot water with a small amount of biodegradable soap, then drain. Repeat the wash and drain process three times in the hottest tap water possible. Finally, rinse at least once in non-soapy water. Then you can dry the seaweed or cook it into a variety of recipes.

Any seaweeds growing near a sewage effluent or by mouths of rivers, bays, or inlets where pollution is being dumped readily pick up the toxins. Such seaweeds should not be eaten. Unfortunately, much of the Southern California coastline south of Malibu should be considered polluted. This means that you have to use some common sense when collecting seaweed for food, and you should thoroughly wash any seaweed you intend to eat.

Eating Seaweeds

Seaweeds can be used in a variety of ways. Some—such as the sea lettuce, which actually looks like sheets of sheer lettuce growing right on the rocks—can be washed and added raw to salads. Other seaweeds are best dried and crumbled, and used as a seasoning for other foods. Some seaweeds can be diced and added to soups and stews. And nearly all can be simply dried and powdered and then used as a salt substitute or flavor enhancer.

If you live near the Atlantic, Pacific, or other coast and have easy access to seaweeds, I encourage you to research the many specific seaweeds used for food. With the many books written about seaweeds, you can find recipes for each of the commonly- used seaweeds, and practice preparing them. And I encourage you to experiment!

Unless you are lost and haven’t the time to experiment or research, there are many sources of information today with many specific recipes and methods of preparation for seaweeds.

One of my favorite recipes from the kelp seaweed is made from the floats, which are the swollen hollow bubble at the base of each frond. I cut them off, wash them, and then soak them in jalapeño juice or other pickling liquids. These floats will take on the flavor of whatever they are seasoned with, and they are served like jalapeño peppers or other garnishes.

Those seaweeds that can be eaten raw can be either eaten fresh (from sea or beach) or dried first and then chewed like jerky. Boiling is preferred in some cases where the seaweeds are bone-dry. Others become more palatable after cooking (up to 30 minutes) in water; both the resulting broth and the seaweed will usually be very good. When the broth cools, it will normally gel, making it useful in various dessert items.

Dried and powdered/shredded seaweed is an excellent item to carry in your survival pack. Placed in a pot of water with other wild vegetables, seaweed makes the closest thing to instant soup that’s available from the wild.

Most of the hollow stalks and air bladders of the brown algae can be eaten raw or pickled. I’ve tried the following recipe with the air bladders of the Pacific Coast kelp, and found it delicious! Pack approximately 100 raw air bladders (alone or with other pickling vegetables, such as cauliflower, onion, and sliced carrot) into clean quart jars. Add apple cider vinegar until the air bladders are nearly covered, and then add one to two tablespoons of cold-pressed olive oil. Sprinkle in your favorite pickling herbs (such as dill seed, tarragon, and celery powder), and add approximately 10 freshly sliced garlic cloves. Cap tightly and shake once or twice a day for a few days. These air bladders can then be eaten as is or as a side to Mexican dishes as a chili pepper substitute.

Many seaweeds can serve the same thickening function as okra does in soups. Tender seaweeds can be added directly to soups; the less tender seaweeds are better broken into bits, blended in an electric blender to a fine mush, then strained through a fine mesh or muslin cloth to remove the solids. Then bottle, label and refrigerate. This liquid can then be used as the soup or gravy base, substituting for flour. The strained-out pulp also has many uses — it can be cooked into homemade ice cream as a smoother/stabilizer, can be used for compost, mulch, or earthworm food, or can be added to animal foods.

Seaweeds have long been used in clambakes. When heated, they give off a steam that adds flavor to other food being cooked near them. Thus, seaweed is thrown directly into large fire pits next to meat, seafood, potatoes, corn and so on. Seaweeds can also flavor and help steam foods at home if you add a layer of them to both the bottom and top of any large pot or roasting pan containing meat or vegetables.

Medicinal Uses

Most iodine is obtained from two sources: brown algae and red algae. Iodine, necessary for the proper functioning of the thyroid gland, has been used for the treatment of goiter for over 5,000 years. Goiter is an enlargement of the thyroid gland, visible as a swelling on the front of the neck.

In his book on nutrition, Are You Confused?, Paavo Airola lists kelp as 1 of the 10 plants that help the body’s glands reach their peak of healthy activity. Many seaweeds — most commonly kelp — when powdered yield potassium chloride, a salt substitute. This is a godsend particularly for those who must restrict the amount of sodium chloride in their diet. By dry weight, kelp is about 30 percent potassium chloride.

The gelatinous material extracted by boiling seaweeds can also be used as a remedy for burns and bruises or as a hand lotion.

One hundred grams of dulse contain 3.2 grams of fat, 296 milligrams of calcium, 267 milligrams of phosphorus, 2,085 milligrams of sodium, and 8,060 milligrams of potassium. One hundred grams of Irish moss contains 1.8 grams of fat, 2.1 grams of fiber, 17.6 grams of ash, 885 milligrams of calcium, 157 milligrams of phosphorus, 8.9 milligrams of iron, 2,892 milligrams of sodium, and 2,844 milligrams of potassium. One hundred grams of kelp contain 1,093 milligrams of calcium, 240 milligrams of phosphorus, 3,000 milligrams of sodium and 5,273 milligrams of potassium.

Other Uses

The long flat stipes of some seaweeds, if treated with a leather softener, can be used as an interim lashing/ binding material (preferably in places where they won’t get wet). The long hollow stipes of some of the kelps have been used as fishing lines for deep-sea fishing by Native Americans in Alaska. These same stipes, along with any of the stringy segments of seaweeds, can, if the need arises, be woven into moccasins, mats, baskets, and pot holders, and even be used for short-term furniture and clothing repair.

Red Tide

When we’re speaking of seaweeds here, we’re speaking of macroscopic marine algae, not microscopic algae. There is something called “red tide” that causes the ocean to look red, and presents a possible hazard if you’re going to collect seaweeds for food. The hazard is actually minor, but you should be aware of this.

According to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “Harmful algal blooms, or HABs, occur when colonies of algae — simple plants that live in the sea and freshwater — grow out of control while producing toxic or harmful effects on people, fish, shellfish, marine mammals and birds. The human illnesses caused by HABs, though rare, can be debilitating or even fatal.

“While many people call these blooms ‘red tides,’ scientists prefer the term harmful algal bloom. One of the best known HABs in the nation occurs nearly every summer along Florida’s Gulf Coast. This bloom, like many HABs, is caused by microscopic algae that produce toxins that kill fish and make shellfish dangerous to eat. The toxins may also make the surrounding air difficult to breathe. As the name suggests, the bloom of algae often turns the water red.

“HABs have been reported in every U.S. coastal state, and their occurrence may be on the rise. HABs are a national concern because they impact not only the health of people and marine ecosystems, but also local and regional economies.

“But not all algal blooms are harmful. Most blooms, in fact, are beneficial because the tiny plants are food for animals in the ocean. In fact, they are the major source of energy that fuels the ocean food web.

“A small percentage of algae, however, produce powerful toxins that can kill fish, shellfish, mammals, and birds, and may directly or indirectly cause illness in people. HABs also include blooms of non-toxic species that have harmful effects on marine ecosystems. For example, when masses of algae die and decompose, the decaying process can deplete oxygen in the water, causing the water to become so low in oxygen animals either leave the area or die.”

Editors Note: A version of this article first appeared in the February 2015 print issue of American Survival Guide.