Tom Grover’s backwoods adventures have filled a lifetime.

Tom Grover is 82 years old, living in Idaho and has been married to his wife, Joyce, for 62 years. And, he’s had a remarkable life.

I began corresponding with him because he was sharing his discoveries about how to make a fire piston that actually worked. He sent me many that worked quite well—much to my surprise (see the related article on the fire pistons here).

Tom and Joyce met in junior high school and got married in 1960.

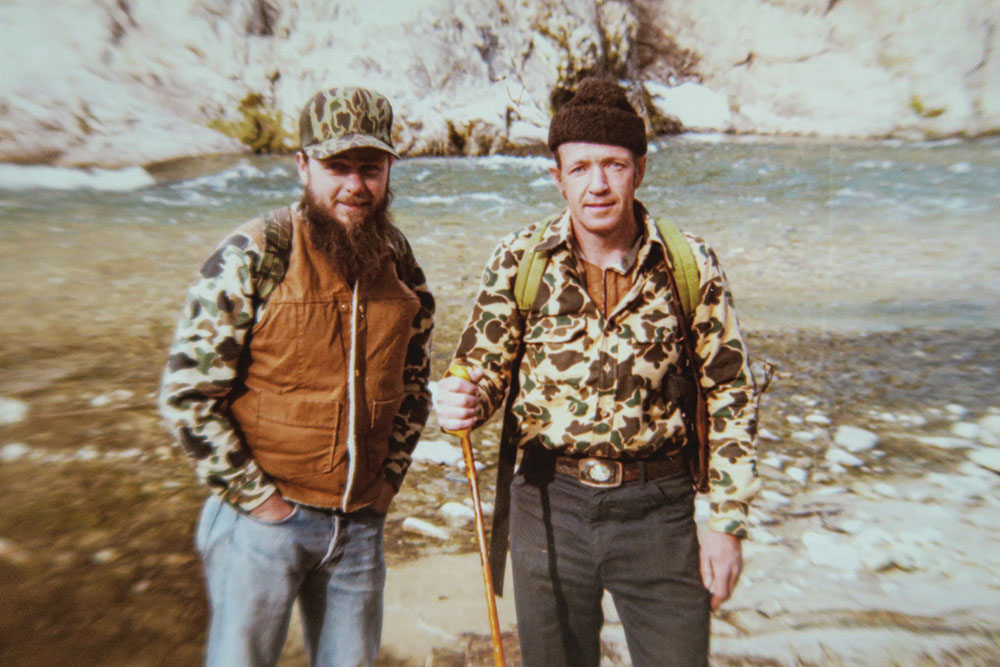

“Joyce and I spent 10 years in a trailer below Palisade Dam at the south fork of the Snake River,” he said. “We lived there from the end of May to October each year, and we went back to Boise for the winter. However, we sold the trailer and the jet boat around 2016.”

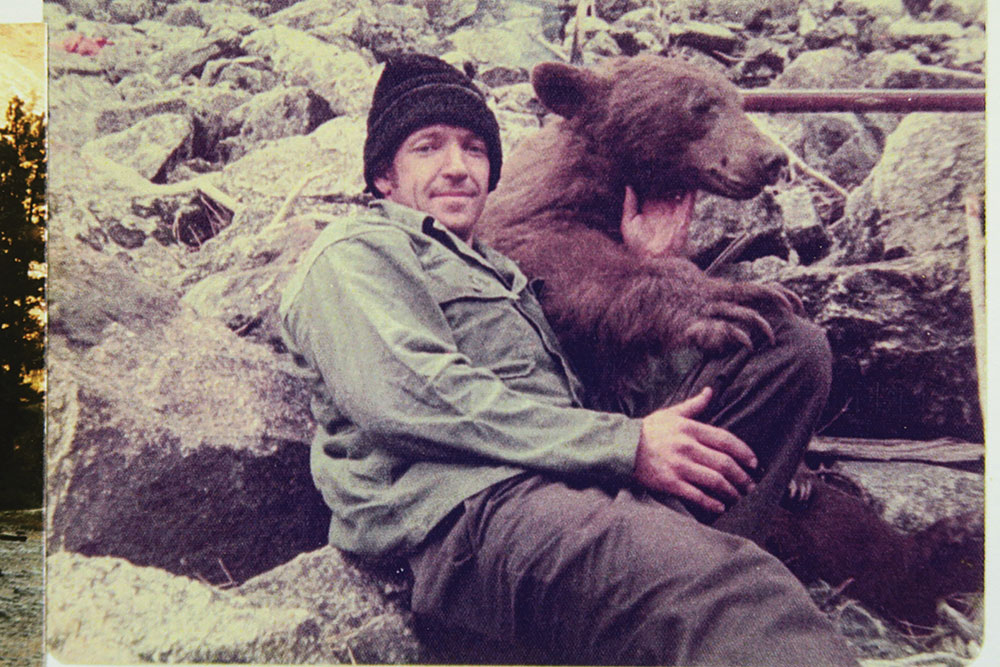

While living in the woods, he ran a trap line (“before I knew better!” Grover quipped). He did lots of hunting, mostly with a handgun, and he has taken bear, deer and elk with it. He pointed out that he’s eaten everything from rattlesnakes to elk in the outdoors.

For six years, Grover was part of the Idaho Air Guard, learning a lot about fire and fighting fires. He lived in the woods most of his life but recently moved into Boise because of age and health issues. He’s lost his hearing and so doesn’t take phone calls. He also doesn’t use e-mail.

BACKGROUND

Tom Grover was born in Driggs, Idaho, on August 20, 1939. His father was an Eagle Scout who guided his son onto a path of wilderness adventures that would last a lifetime.

“Life in the woods was simple, with the hard work of cutting fire wood—lots of fire wood,” explained Grover. “After Dad died, Mom was alone in the woods. There was a very big pine tree leaning over the cabin, and she was afraid it would fall on the cabin. No one would cut it down. So, I told her, ‘I’ll cut it down.’”

“’The flint-and-steel method is as simple as it gets,’ he said. ‘It’s worked very well for thousands of years.’”

Grover got a 5/8-inch-diameter cable, climbed up the tree and hooked onto it. He then ran the cable around another nearby big tree, which he thought was a good plan. He began to cut with his 36-inch chainsaw and felt he was doing everything right. But, when the tree started to fall, the chainsaw stuck, and Grover said he “ran like hell” to get out of the way.

The cable snapped as if it were just a string, and the top of the tree went right into the cabin’s roof—right to the floor of the cabin.

“Mom had a very nice Christmas tree from the floor right out the roof. Life in the woods!” Grover joked.

“ … Grover described himself as a long-time primitive fire-starting hobbyist. He’s taken classes on primitive fire-starting and done extensive experimenting with flint-and-steel variations, the bow and drill and the many possible tinders.”

Grover explained that he hunted alone the majority of the time. He learned a lot about survival from Tom Brown Jr. and the Woodsmoke journals. He also learned a lot from Scriptures.

“What worked 2,500 years ago worked a lot better than the modern-day, unnecessarily complicated B.S.,” he pointed out.

RIVER ADVENTURES

Grover said that he was a die-hard canoer, using a pole, and has traveled more than 3,000 miles by canoe.

“I think I’m the only person ever to pole up north of Boise River to French Creek and back. It’s a very narrow canyon, with fast, rocky water. The territory has lots of rattlesnakes, bears, wolves, mountain lions, deer and elk. It took me three days.”

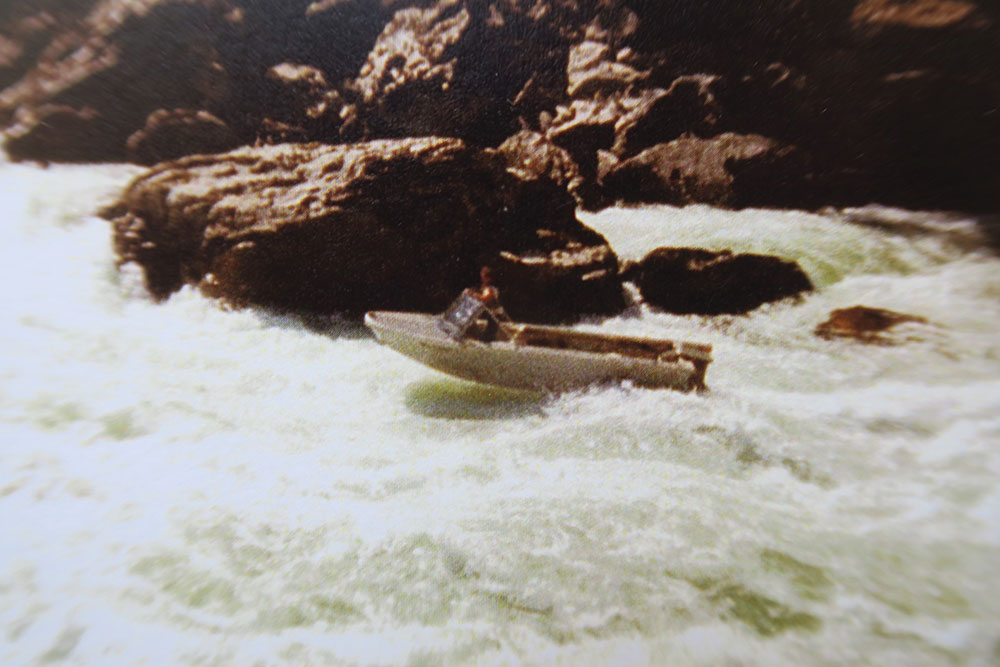

He’s also run white-water jet boats on six Western rivers and says he’s been a “rock hound” since his childhood.

“A man working for Steward Gem Shop showed me how simple it was,” Grover explained. “My first ‘cab’ took me eight hours to make, and my last one took only 15 minutes. I’ve made lot of cabs out of agate and jasper. A ‘cab’ is properly called a ‘cabochon,’ which is a gemstone that’s been shaped and polished instead of faceted. These stones typically have a flat side and one domed side. I use the broken slabs for the flint-and-steel method of fire-starting.

“Joyce always wanted me to bring home a rock. My friend, Jim Powell, and I had been up on the Salmon River in Jim’s jet boat, and when I got home, Joyce asked, ‘Did you bring me a rock?’ Jim replied that we did, and that it was a nice ‘Indian love stone.’ Joyce was very happy, but she wanted to know exactly what an Indian love stone was, because it was something she hadn’t heard of before. It turns out it was just a common rock!”

“’What got me started on a better fire-starter was the winter my canoe capsized in the rugged Buckhorn Rapids of the North Fork Canyon.'”

According to Grover, “Joyce always said that I was the most dangerous person she ever saw. It’s actually the result of ADHD (Attention Deficit Disorder). But it saved my life several times, because I just do things without thinking.”

FIRE-STARTERS

“What got me started on a better fire-starter was the winter my canoe capsized in the rugged Buckhorn Rapids of the North Fork Canyon. I’d stuck my canoe pole down to turn around and look upstream, but it got stuck between two rocks. I fell out of the canoe while trying to get my pole free.

“Temperatures were near zero, and I was alone. The difference between life and death was probably about a minute. But my ADHD saved my life, because I didn’t get scared. I just did what I had to do without thinking about it—and very fast. I found wonderful pine pitch vapors and learned how to use them. They’re the easiest and best fire-starters on Earth (I think I had help from God on that one).”

“‘I’d stuck my canoe pole down to turn around and look upstream, but it got stuck between two rocks. I fell out of the canoe while trying to get my pole free … Temperatures were near zero, and I was alone. The difference between life and death was probably about a minute.'”

In fact, Grover described himself as a long-time primitive fire-starting hobbyist. He’s taken classes on primitive fire-starting and done extensive experimenting with flint-and-steel variations, the bow and drill and the many possible tinders.

“Primitive fire-starting has been a lifelong hobby—flint and steel, bow and drill and fire pistons. I started my first primitive fire 68 years ago. My last class in primitive fire-starting was five years ago. My first class in survival was 57 years ago.”

Grover spent 40 years with the Boy Scouts, for which he taught most of its wilderness survival classes. He was a Wilderness Survival merit badge counselor for 20 years and also taught canoeing and primitive fire-starting.

“I was probably the first to lead Boy Scouts on a 50-mile canoe trip in the Bird of Prey Snake River Canyon,” he pointed out.

Then, he began to explore the fire piston.

“I got interested in the fire piston because my wife gave me one as a gift. It worked about as well as wet gun powder (author’s note: That was also my conclusion!).” However, Grover was not content with that. “So, I decided to make my own, to see what works and what doesn’t work. I spent a lot of time starting fires with the fire piston using pine pitch and fatwood and with jute string for tinder. Then, I tried with just fatwood and charred four-ply jute cloth; nothing else. I’ve started fires in the mountains with a fire piston throughout the entire year. I have one fire piston that I’ve used 327 times to make a fire.”

Grover is also a big fan of flint and steel.

“The flint-and-steel method is as simple as it gets,” he said. “It’s worked very well for thousands of years. Flint and steel and a good bamboo sulfur stick are very hard to beat and are much better than a strike-anywhere match. It’s very easy to start a fire in less than a minute.”

According to Grover, “Bird’s nests (for tinder) are a modern-day thing and were seldom used 200 years ago. A good, primitive fire-starter can start a primitive fire without a bird’s nest, tinder box, sulfur stick or gun powder.”

TOM GROVER ALSO MAKES HIS OWN KNIVES

Among his many other skills, Tom Grover has lots of metal yard art and lots of homemade knives. He sent me an incredible machete-like knife he made by hand from an old saw blade. It’s a truly functional work of art. It measures slightly more than 19 inches from the tip to the end of the handle and features a full tang.

“I once read a book on how to make knives, and then I just proceeded with trial and error. I think metal-working was a God-given talent that I didn’t know I had until I was 70 years old. Comes from my ADHD, I think,” he said.

“I made my big knife out of a 36-inch chainsaw bar. I made it more than 20 years ago, and it’s still a very good knife. I’ve chopped logs up 12 inches in diameter. I’ve also used the back of the blade as a sort of broom to clean the ground for an unexpected night out.”

A MAN OF STRONG BELIEFS

“I don’t belong to the ‘no-God’ or ‘no-use-for-God’ world,” Grover wrote in one of his letters to me. “I try to read the Scriptures every day and say my prayers three times every day, 365 days a year. Anyone who thinks I’d do that year after year if it were one-sided is very stupid!

“My father drilled two things into me,” he added. “One: Never hit a woman. And two: The only reason for being late is if you’re dead. I have zero tolerance for either one. Love is the power that holds friends and family values intact.”

A version of this article first appeared in the February 2022 issue of American Outdoor Guide Boundless.