NATURAL NAVIGATION WITHOUT A PHONE APP, GPS OR COMPASS

In his book “The Natural Navigator,” Tristan Gooley points out that most of us have lost the ability to naturally navigate our terrain because of the preponderance of modern devices.

We rely on the GPS in our cell phone, and we assume it’s always correct, so less and less do we tend to think for ourselves. Whether the modern device is used by a hiker, a motorist, or a someone sailing at sea, nearly everyone relies on the modern technologies, and barely at all do we rely on our own natural powers of observation.

MANY NATURAL SIGNS

Natural navigation is not just one thing — it is many things. It is watching the way the sun moves, observing stars, watching shadows, watching how paint weathers faster on the south sides of buildings and not so fast on the north side. Natural navigation includes watching how snow melts, observing animals and trees, observing the wind, and taking note of distinct odors.

Here are just a few of these basic observational skills that we should revive in our own personal lives.

OBSERVING A SHADOW

It sounds simplistic, but when you observe the shadow that is cast from the stick, you can learn everything you need to know about the movement of the sun. Really!

As Gooley said, “It is important to hold on to the idea that there is nothing about the movement of the sun that cannot be understood by putting a stick in the ground and watching its shadow.”

In my classes in natural navigations, we always make the shadow compass, and it is as accurate as the compass (maybe more accurate) for determining true north and south.

Here is what you do.

Place a stick into the ground. Put a pebble at the end of the shadow. Wait 20 minutes or so. The shadow will have moved, so put another pebble at the end of the shadow. Wait another 20 minutes and do this again.

When you’re in the northern hemisphere, your shadow will be pointing toward the north if the stick is stuck vertically into the ground.

The shadow’s movement, marked by the pebbles, will be eastward, because the sun moves westward. The shadow should be the shortest around noon, when the sun is directly overhead (directly overhead at 1 p.m. if it is during Daylight Savings Time.)

If you draw a straight line from the stick to the stone marking the shortest shadow, you should have a north-south line, more or less. A perpendicular line gives you an east-west line, and your crude compass.

Natural observations

You have no map, no compass, and you’re lost or confused. Are there signs in nature to tell you directions?

We have long heard that moss grows on the north side of trees. Yes, it does, but it also grows on the east side, the south side, and the west side of trees, especially in a dense forest where there is little light. While there is logic to this idea,

it’s not always accurate.

TREES

Prevailing winds, especially in canyons, can cause the tips of certain trees to point in specific directions. For example, the tops of willows, poplars, and alders often point south because they grow typically in canyons or streams, and the predominant wind is often downstream, or southward. Note, “often,” not “always.” A stream can have lots of bends and curves and so this is only a general observation that can help, in conjunction with other observations.

The tips of pines and hemlocks often point east. These trees are typically found at higher elevations and the tips are affected by prevailing winds. Again, the operative word here is “often,” not “always.”

FACING THE SUN

Flowers often face the sun. This is where sunflowers (and the Sunflower family as a whole) got its name. You can point a time-lapse camera at a sunflower and watch it move throughout the day to face the sun as the sun moves across the sky.

Certain spider webs nearly always face the southern direction because it is warmer for the spider to face the southerly direction.

Keep in mind that “facing south” in these cases refers to anywhere from the south-east to the south-west, nearly a full 180 degrees of the horizon.

“The North Star is NOT the brightest star in the sky”

Any hill or mountain range which runs in an east-west direction will receive the most vegetation on the north side. The south side – exposed more to the sun, will have different plant communities and generally be drier. The north side will retain snow longer, and will have more shade, and thus more ferns, moss, etc.

ANOTHER GOOD SOURCE

Aside from “The Natural Navigator” by Tristan Gooley, another great book on this topic is “Finding Your Way Without Map or Compass” by Harold Gatty, published by Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, NY. This comprehensive book is available at Amazon.com for $12.39.

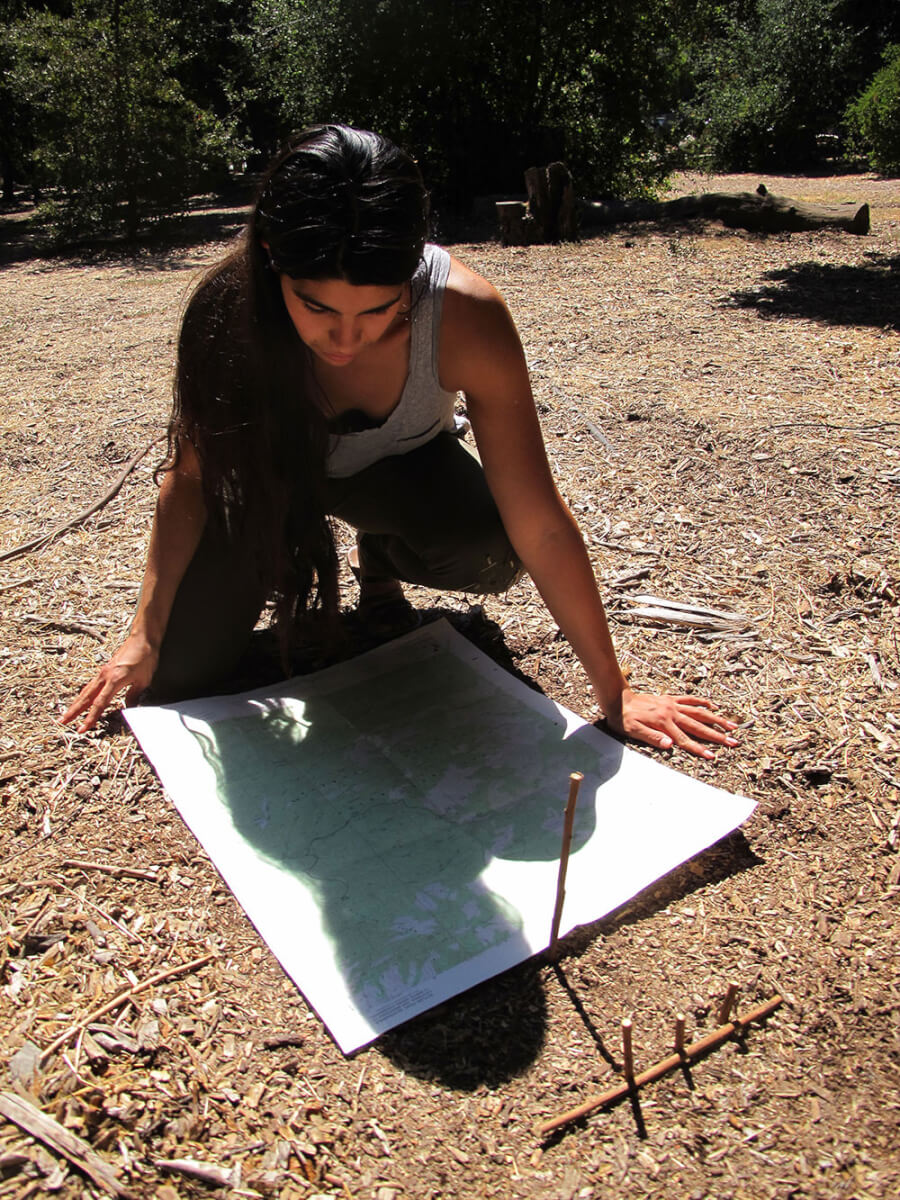

If You Have a Map

You need to get from Point A to Point Z on foot, and you have a map.

The map is an aerial picture of your terrain, showing you the location of roads, buildings, water, towns, railroad lines, mines – everything you need to know. The USGS topographical map is the map of choice because it gives you a visual depiction of the rise and fall of the land. This enables you to choose the easiest route (which is not necessarily the shortest) between two points.

With a map of your terrain, there are at least three simple ways that you can align it with the actual terrain even if you don’t have a compass: Direct observation, the North Star, and the sun.

The Sun

We’ve already described how to scribe a fairly accurate north-south line using a shadow stick. OK, so if it’s daytime, make a shadow stick, and figure out the location of north. Then, simply align your map so that the north on your map is lined up with true north.

Direct Observation

To accurately align your map with the actual terrain requires the ability to make several observations of features in your area, such as a distinctive high peak, a water tower on top of a hill, and any features that you can actually see. You might need to get up high to observe your terrain if you’re in a low area.

Then, start observing, and turn your map until it lines up with the terrain. Then you can study the map to determine where you need to go.

Stars

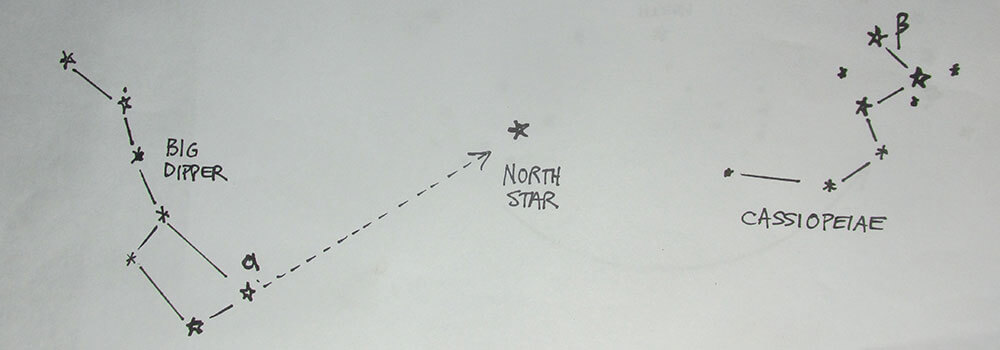

Though it’s possible to determine cardinal directions from any stars, it will likely take a bit of practice in the beginning. Start your natural navigation by learning how to identify the North Star. The North Star is NOT the brightest star in the sky. If you follow it with time lapse photography, the North Star will appear to be stationary, and all the stars would appear to rotate counter-clockwise around it. If you were standing on the north pole, the North Star would be directly overhead. Time lapse photography is capturing the rotation of the earth.

North Star

To find the North Star with natural navigation, locate the Big Dipper. The North Star is in a direct line with the two end stars of the Big Dipper (see illustration). Once you’ve located the North Star, you can turn your map so that the north end of your map lines up with true north. The North Star is about one degree off from the Celestial North Pole, so it’s a very accurate method for determining north in any given area of the northern hemisphere.

Editor’s Note:

Nyerges has been teaching outdoor skills since 1974, and is the co-founder of School of Self-Reliance. He is the author of several books, and can be reached at www.schoolofself-reliance.com.

A version of this article first appeared in the March 2022 print issue of American Outdoor Guide.