Jungles are literally and figuratively crawling with nasties from canopy to floor. Vegetation foreign to travelers hide three inch long thorns, crawling leeches, leaf-cutting ants, fast moving spiders and countless other insects, some of which may remain undiscovered and are completely unknown to scientists. Thorny tree trunks, acid-covered leaves and reptiles also call the jungle home and contribute to the inhospitable environment where everything seems to move and come alive.

Despite the high heat, near 100 percent humidity, insects and regular heavy rain, there is an allure to the jungle which draws thousands of explorers each year to the tropics and subtropics. The adventurer need not board a plane though to experience jungle-like conditions, as American swamps, glades and wilderness areas from Alaska to Maine, Michigan and Florida and all points in between are infested with their own dangerous residents and defensive flora.

With careful preparation, the choice of clothing one packs can make the difference between relative comfort and absolute misery. Beyond clothing, there are many skills and bits of knowledge locals have learned to mitigate the potential threats, allowing the explorer to enjoy their surroundings. These concepts can be applied anywhere and will improve survivability in jungle conditions and when surrounded by insects.

WETNESS COVERS ALL

One aspect of the jungle an outdoorsman must accept is the near constant state of wet experienced while traveling through it. The combination of humidity and sweat requires clothing that dries easily and breathes well. For this reason, coated nylon is less desirable than garments with some percentage of cotton in their fabric or those designed for conditions like these. Full cotton and cotton blends are other options but they will not dry as quickly as those with more nylon content.

Some of these advanced fabrics are impregnated with proprietary insect treatments guaranteed for “x” amount of washings. Don’t take chances, be sure to apply permethrin to your travel wear prior to heading out. For short term trips, both blended and pure cotton are fine but, on longer trips, the ability to get relatively dry will improve your morale. Morale is not the only characteristic of the jungle travel preserved, hygiene will be as well. Prolonged exposure to wet clothing leaves skin softer and more prone to blistering, tearing and abrading if mixed with abrasives like mud or under the stress of pack shoulder and waist straps. It’s also important to wear clothes that are loose fitting. Tight compression-style shorts and shirts are significantly warmer and use more synthetics than natural fabric construction. If a second set of undergarments and socks can be carried in a small bag, the ability to change into anything dry at the end of the night is a welcomed luxury.

COLOR MEANS EVERYTHING

Jungle plants want to poke, prick, scratch and impale you at every turn. Clothing helps prevent injury in an environment where infection can easily set in.

Recently, while in Costa Rica, I was reminded of the value of light colored fabrics. In addition to absorbing less sunlight and therefore less heat, the light fabrics also helped me identify ticks (not the Lyme disease carrying variety, but still an annoyance) crawling on my pant legs. If you are aware of a particular threat, consider wearing clothes that contrast with the colors of that threat. Deer ticks in the Northeast are brownish and are easily spotted on light green, tan, white and light blue clothing. Speaking of ticks and other bugs that find their way into tight places, bloused pants or boots with laces tied around the ankle will prevent ticks from making their way up your legs and gloves with wrist fasteners will keep them from going up your sleeve. Even if you take precautions to prevent insects from entering from your ankles and wrists, you should still make it a regular routine to use a mirror (the inside of your mirrored compass works well) to check your armpits, waistline, groin and other warm areas. Regardless of how well you assume your clothing will ward off these pests, do not disregard this practice. A friend of mine assumed he was free of ticks because he was seated in a canoe paddling through thick grass. At the end of the day, he had a tick buried in the sweaty crease of the back of his knee. Don’t get too comfortable or you invite trouble.

CLOTHING SELECTION

When selecting clothes for the jungle, the swamp or the glades, one should also consider a good wide-brim hat and gloves. I prefer a wraparound brim over a baseball cap as that style protects my face from sharp vegetation and it also protects both my head and neck from the sun when out from under the canopy. Wide brim hats can be treated with permethrin just as easily as clothing. Deer hunters here in Connecticut, home of the original Lyme disease case, swear ticks wait to fall on hosts from overhanging branches. A good wide brim hat can prevent insects from literally jumping down your neck. Often, many of these hats are equipped with some sort of brim strap that can be used to hold chemical insect repellent strips. When using repellents of extremely strong DEET concentration, avoid using it on synthetic clothing and plastic watchbands, eyewear frames and other accessories as it can rapidly disintegrate those materials. When taking off your hat at the end of the night, always examine your hairline and hatband line for ticks. Run your fingers through your hair or carry a fine-tooth comb and comb gently. You don’t want to crush the body of a disease carrying insect. Remove these with a good pair of tweezers or have a trusted friend do it if it’s in a spot that’s hard to reach.

Gloves might seem like overkill in the outdoors but they protect your valuable sense of touch. A few encounters with razor grass and you’ll understand why it makes sense to wear gloves and move vegetation out of the way rather than walking, hands up, switching from side to side moving flank first through the most convenient path. My Filipino relatives learned the value of carrying walking sticks with natural hook features formed from branches. These can be used to move vegetation out of the way, to examine the ground for anything they didn’t want to step on or to reach edible fruit outside of reach or within the protective guard of a thorny tree. There are not only thorns in the jungle but plants with oils and irritants on fine hairs that cause skin rashes. In the United States, all three big poisons (Oak, Ivy and Sumac) have urushiol oil that causes dermatitis. Be warned, your gloves may collect those irritants and you may inadvertently spread it if you rub your eyes or other parts of your body while wearing your gloves. Water-resistant gloves are not necessary but gloves with a leather palm are. I’ve had very good success with gloves meant for rappelling and working with wire cable. Just as wire fibers can slash your hand and stick you, jungle thorns can as well. A couple words of warning about gloves- Check them and shake them out if you haven’t worn them for a while as something unpleasant may have made them a temporary home. Also, be careful to dry out your gloves and treat them with conditioner (not waterproofing agent) if they feel too dry after your trip. This will extend the life of the leather.

PROTECT YOUR FEET

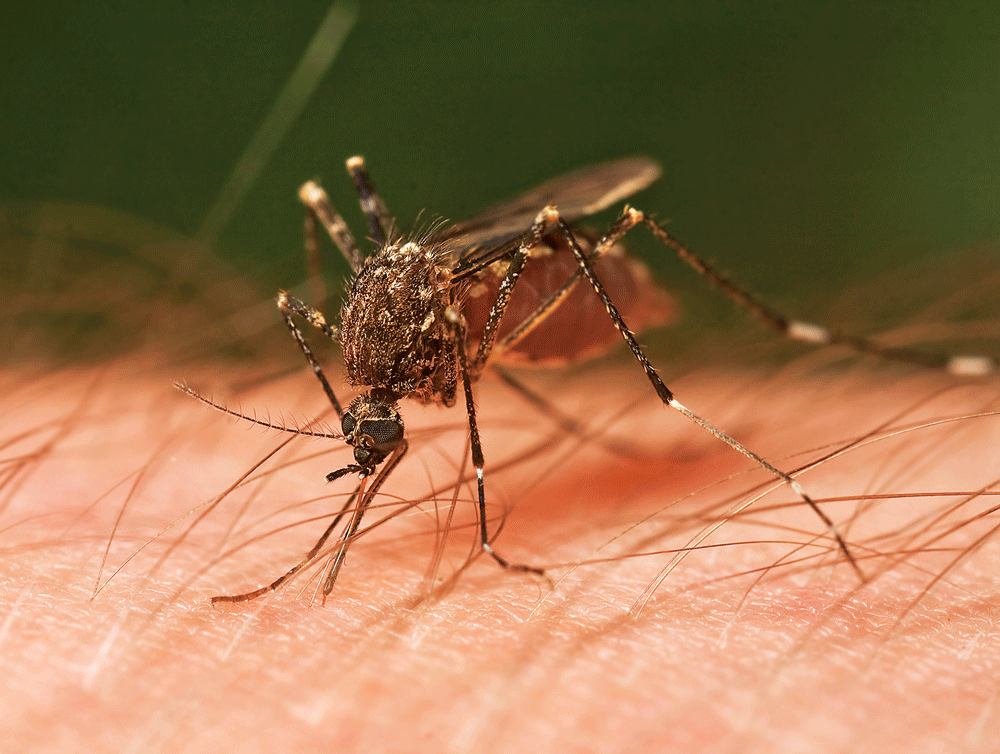

Just as important as protecting your hands is protecting your feet. Modern jungle boots often draw inspiration from those worn by the U.S. military during the Vietnam conflict. They are roughly eight inches high, have a self-cleaning tread and are constructed with wet weather and mud in mind. They won’t protect your feet from getting wet but they will dry faster than conventional boots. I prefer closed toed shoes in the jungle unless I’m in a camp or a swimming hole. Leeches do not come in one size and they can be exceptionally annoying in their persistence to penetrate any opening in your clothing defense. Lacing eyelets can be an entry point unless the tongue of the boot is attached to the upper. Also, a potential weak point is the drainage holes many footwear manufacturers are putting on the side of their shoes. These drainage holes should have a mesh backing if they are truly meant to offer protection above the benefit of draining water. This attention to detail will save you the horror of finding a leech that entered your shoe and has been gorging itself on your blood and is now many times its original size. Thanks to the anesthetic in leech saliva, you won’t feel it bite and only the occasional wiggle can give away the presence. Should you find one on you, use citric acid, salt or a match to remove it. Don’t be alarmed if you notice the bite mark bleeding for a length of time after the leech is removed. There is yet another substance in the saliva that acts like an anticoagulant that will eventually wear off. Drainage holes will function better than full Gore-Tex booties that act like personal foot bath tubs leading to a bevy of foot ailments by never allowing feet to dry.

“LEECHES DO NOT COME IN ONE SIZE AND THEY CAN BE EXCEPTIONALLY ANNOYING IN THEIR PERSISTENCE TO PENETRATE ANY OPENING IN YOUR CLOTHING DEFENSE.”

STAY RESTED

Assuming you are spending more than a single day in the jungle or jungle- like conditions, it is important to never underestimate the value of sleep and to have a sleep suit. This second pair of clothes is worn inside your shelter and kept dry as much as possible. It is free of dirt, crushed insects from swatting at them all day, blood, sweat, insect repellent odor and funk. Part of the sleep suit in really buzzing environments is a cheap pair of earplugs. Assuming you are in a group setting where there is collective security, the foam ear plugs will suppress the sounds of insects that can keep you awake or play games with your mind thinking one slipped inside your hammock or tent. Whenever hammock camping, my routine prior to swinging for the night includes putting on a pair of hiking socks with a terry cloth-like interior after powdering my feet with medicated powder or baby powder. Also, prior to retiring for the night, it is not uncommon for moss to be used in smudge pots made from adding campfire coals to metal cans with wet vegetation on top. Used around the perimeter of your camp, you can smoke out some of the flying nuisances around you at least long enough to get you to sleep before the coals burn out. Sleep is truly underrated in the outdoors while afield. The jungle, glades and swamp are home to nocturnal animals that will interfere with your recovery and rest time. Spend enough days getting little to no sleep and the stacked insomnia can lead to potentially hazardous issues during your day.

With proper planning, it is possible to enjoy the jungle, or places like it, in relative if not complete comfort. All the sights, sounds and smells of the jungle can be appreciated with the correct jungle clothing choices and by following indigenous information. When you realize you are merely a guest in the jungle and change your perspective of man vs. wild to man in wild, you begin to understand and accept the flora and fauna and how best to deal with them. The jungle becomes more inviting and you will start planning your next trip before you even make it home.

The All Important Jungle Blade

If I had to choose one blade for the jungle, I’d make mine a machete. The jungle is filled with green vegetation that a long, fast-moving and thin blade can cut through easily. The machete is also a “do all” blade and as long as the user knows how to handle it, it can chop, dig, skin, carve, shave and draw cut. Many reputable makers are producing quality machetes and, as long as the user is willing to put time behind the blade, the machete will help make jungle travel safer.

Since the machete is the tool used predominantly, the handle should be comfortable and the blade the correct size and length for the user. Too long a blade and the machete will be hard to use in tight quarters. Too light and not enough mass will be available to make effective use of the blade.

On any machete I carry into the field, I attach a small bastard file to the scabbard. This file is meant to repair any larger chips or rolls accidentally caused by misuse or an errant swing. Whenever in the field, I tend to two-hand carry my machete, slung over my shoulder baldric-style so I can at least pivot the sling to allow easy cross draw of the blade. This allows me to easily access it quickly if needed. It also allows me to carry a small flashlight, in the same hand as the sheath, pointed in my direction of travel. There’s no need to walk into objects in the dark you could otherwise avoid.

The machete is more than a great tool for the jungle; it excels in the hardwoods too. Machetes don’t bind in wood as readily as thicker bladed knives and a compact 12-inch machete, properly ground, will out-cut custom knives many times the value of the economical machete. With proper technique and experience, the best tool for the jungle becomes a great choice for just about any other environment too.

THE JUNGLE HAMMOCK

The jungle floor is home to countless insects that star in countless nightmares. Spiders, scorpions, centipedes and beetles are not what you want to find on your body when you wake up. Getting off the jungle floor is important and when it comes to a good night’s sleep, nothing beats a jungle hammock. Of all the hammocks on the market, Clark Hammocks is well-known and considered the industry leader in anti-insect research and field testing.

The Clark Jungle hammock is meant for the worst conditions. The hammock is part of a larger set in the shelter system. The hammock body has attached mosquito netting for seamless protection. The spacer bars provide the all-important distance that keeps the hammock spread open allowing the user to sleep unmolested from mosquito stingers. These spreaders also allow a natural sleeping position without pressure on the shoulders causing a stiff neck.

The Clark Jungle Hammock has been improved over the years to include drip rings that prevent water from running down the support straps. To keep ants from making their way down just as easily, some users smear toothpaste on the straps and report great effectiveness. Certain models of the Jungle Hammock have an integral pocket on the bottom for a sleeping pad or to store gear off the ground. Wake up to a lizard or snake in your boot and you’ll consider hanging or storing them at night.

Clark continues to do research in the field of anti-mosquito protection. Product testing in the field in the Amazon has resulted in advancements in their design and construction methods. Their product line is among the best out there and can be used during all seasons and in almost any conditions.

NATURAL INSECT REPELLENTS

It is said mud is an excellent insect repellent when applied to the skin. This is somewhat true. Mud can be used to mask unfamiliar smells that draw insects in. Mud can also be used to cover exposed skin if no other option is present. Mud will eventually dry out and must be reapplied regularly. There are also some stinging insects that can penetrate a relatively thick layer of mud regardless of the efforts in applying it.

In North America, cedar trees are relatively common and some people will use the smoke from cedar to smudge their clothing and person to ward off mosquitoes. Another common natural repellent is tobacco and fishermen have long advocated smoking cigars for the same reason. These two natural plants have roots in certain Native American cultures.

A natural diet, one free of processed foods and local to your area of operation is also said to help prevent insects from bothering you. People are what they eat and just as some will claim they can “sweat garlic”, pheromones we cannot detect are believed to be secreted from the body. These inconspicuous odors may contribute to claims insects are often worse at the beginning of an extended trip than they are at the end.

Natural insect repellents have questionable effectiveness. If a supply of commercial repellent runs out, knowledge of these may provide some comfort even if that is more psychological than physical. Knowledge weighs nothing and is always with you. Sometimes like the mosquitoes that always seem to be there too.

Editors Note: A version of this article first appeared in the June 2015 print issue of American Survival Guide.