Day Five. The water just ran out. The water pressure fell to a dribble, and your three-year-old daughter just sipped down the last capful from the reserves you thought you would never need. Quarantine. Isolation. Sequestration. The house has been boarded up and barricaded since Tuesday, the same day the National Guard pulled out. Ten gallons sounded like enough water to last longer than it did, but with a family of five in the heat of a sweltering house, you consumed more than you planned. Without proper water storage, your days are numbered. If only you had better prepared by storing more water you might have been able to stay put and survive the calamity. But now, you’ve got to move.

“WITHOUT PROPER WATER STORAGE, YOUR DAYS ARE NUMBERED.”

THE WATER STORAGE CONCEPT

You never know what will happen — earthquake, tornado, civil unrest, economic and social upheaval that affects the basic services in your area. You can do without food, without a knife or ammunition or a can opener, but the moment the water runs out, you’ve gone from a serious situation to a dire emergency. In planning your emergency cache, not enough effort can be spent on water storage solutions. This means filters, purifiers, chemical tablets, and even rudimentary water sanitizers like bleach and chlorine. But it also means water, lots of water.

“IF IT IS AN EARTHQUAKE OR FLOOD, THE FIRST THINGS TO GO ARE CITY SERVICES.”

Depending on your personal situation and a lot of different factors like climate and local weather, the average person uses one gallon of water per day, split between drinking, cooking, and hygiene. Sure, drinking and cooking can be modified or eliminated in the factor, but it still must be considered. The Center for Disease Control says that a three-day supply should be kept on-hand at all times but suggests keeping two weeks’ worth of water. Three days of water for a family of five is 15 gallons, while two weeks’ worth of water is 70 gallons. Indeed that is a lot of water, which will take up a lot of space (think about the space needed to store 14 five-gallon containers of water, the kind you’d find on top of a typical office water cooler). Of course, there are other containers available.

WHERE TO STORE WATER

One of the largest problems with storing water, aside from making it potable, is the physical space limitations a lot of people might have. As mentioned earlier, 70 gallons is a twoweek supply for a family of five, and there are many ways to make that possible.

Store-Bought Water Bottles: An inexpensive route would be to buy many cases of store-bought water. Even cheaply from the big-box stores, to fit the requirements set above, a 24-pack case of 16.9-ounce water bottles equals about 3.2 gallons, meaning you would need 22 cases of water. At about $4 each, it’s about $90. However, theories and arguments abound about whether or not plastic bottles are safe to keep long-term (see sidebar). Because of this, it’s a good idea to rotate out your water cache every eight to 12 months, and it’s simple: When you buy a new case of water for regular consumption, date and replace it with the oldest case of water in your supply.

Multi-Gallon Jugs: Many retail stores offer three-, five-, and seven-gallon water bottles to be used with water coolers. They are a great storage solution in that you can easily store a large amount of water in the smallest space possible. But typical water bottles don’t stack and they’re made from clear plastic (consider algae growth). Unless you also buy the plastic crates or custom build a shelf system, you’ll have water bottles strewn about. There are some companies that offer stackable water containers made with food-grade plastic that are great for tight spaces and are easily transportable.

Water Barrels: A great solution if you have the space is to incorporate 55-gallon plastic drums into your emergency cache of supplies. They are Bisphenol A (BPA)-free and UV-resistant because of their opaque plastic, incredibly sturdy, and, as seen on this month’s cover, can be used to make a very buoyant life raft. They’re not very portable (full, each weigh close to 500 pounds), they take up a lot of space (at 38-inches tall), but offer a lot of water. Two 55-gallon barrels will provide almost a month of water for a family of five.

Brand new, these barrels are rather expensive, but they can be had cheaper if previous used. Find out what was stored in them before you buy them used (avoid those used for chemical storage) and always make sure to properly clean them no matter what. Again, there are arguments about long-term filling and storage. Some say not to store them on concrete as it will adversely react with the plastic, and many suggest using a food-grade hose (for an RV) to fill/empty them. To be on the safe side, put them on a square of carpet or some cardboard.

Rain Barrels: Larger still are rain barrels that collect water from your roof. This is an economic way to passively collect a lot of water, but it comes with hazards and legal questions.

Hazards: In a study by the Texas Water Development Board in 2010, it was discovered that rainwater rinsing off of roofs made from typical materials such as asphalt, wood, concrete, and steel, contain high concentrations of lead, copper, zinc, and other dangerous metals. Additionally, asphalt shingles contain small amounts of chemicals, such as benzo(a)pyrene, which has been identified as a carcinogenic. Because of this, it is best that this water be reserved for maintaining crops or for cleaning.

Legality: Before setting up a rainwater collection system, check your local laws about the legality of doing so. Because some cities rely on treated rainwater to supply its inhabitants (or laws protecting people from the hazards mentioned above or contaminating the ground water), it might be illegal to harvest rainwater in your area (mostly you just need a permit to do so).

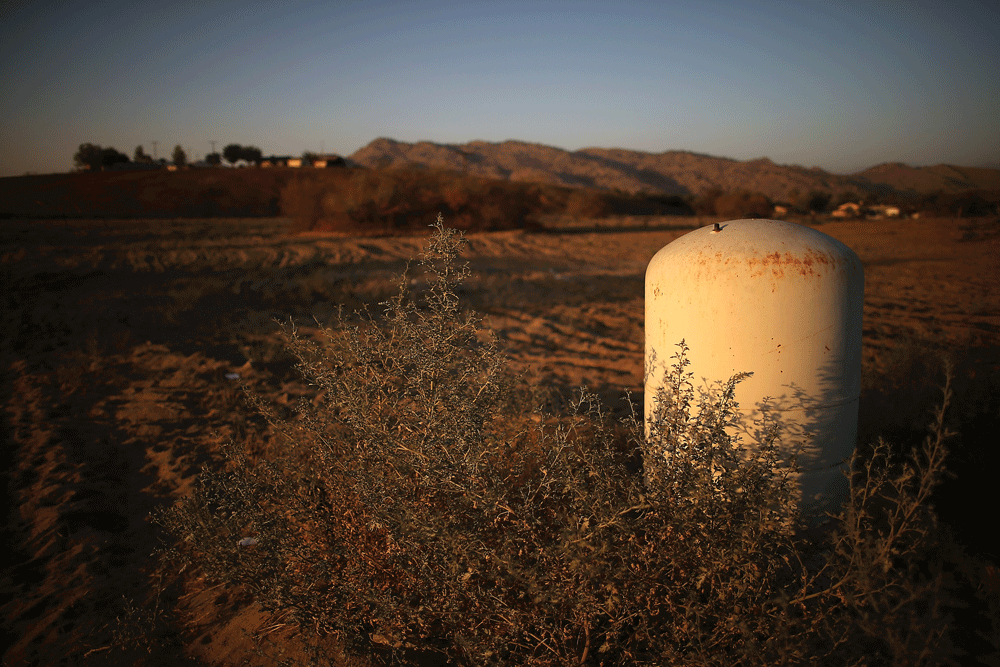

Water Cisterns: These are for serious water hoarders who want or need a supply of water that can last for months if not years. A huge cistern tank of approximately 10,000 gallons can last a family of five around five years. If you have the space to store it (or perhaps an underground storage bunker), a giant cistern is a great investment. And it is an investment, because they are relatively expensive and require a great deal of maintenance, especially if stored underground and supplied via rainwater. The only problem is that most of these systems are not food-grade friendly, so the water will have to be filtered in order to drink it.

HOW TO TREAT WATER

The big issue with storing water for long-term use is to make sure that it is potable when the time comes to break into your supply. A concept to understand is that water doesn’t have an expiration date. The very water you’re drinking today has been around since the beginning of time (it has been suggested that every drop of water on earth has already been through the digestive tracts of many animals, from the dinosaurs to your neighbor), and it’ll never go “bad” if properly stored. What causes water to become undrinkable is the contaminants that gets into it. Chemicals, algae, bacteria, and biologicals that get into your water will ruin it in a couple of days if not immediately.

Water should be completely sealed in an air-tight, opaque container. It should never be opened unless it is to be used. It should be kept in a relatively cool place (or at least where temperatures don’t fluctuate too broadly). If you fill your containers with tap water, theoretically you won’t need to treat it with anything, like chlorine or iodine, before you seal the container. Water directly from tap is already treated with chemicals to keep it free of water-borne contaminants and algae/bacteria. However, to be on the safe side, you can add an additional 1/8 teaspoon of chlorine per gallon of water. For a 55-gallon drum of water, you’ll need seven teaspoons of chlorine to treat it properly. If your city’s water supply is well chlorinated, you can skip this, but chlorine can be added after you open the container.

Another viable option is to add an over-the-counter water treatment chemical specifically designed to purify water for immediate drinking or long-term storage. Most products offer colorless and odorless additives that won’t have the aftertaste that chlorine or iodine does.

Note that water stored for a long time will lack oxygen, which will give it an overall flat taste. To remedy this, just stir it up a little bit, as that flat taste doesn’t mean anything is wrong with your water. However, if you think that contaminants leached into your supply, just boil it.

WATER IS LIFE

Once your water storage system is in place, forget about it. Rotate the plastic water bottles when it is convenient to do so, but for the larger containers, let them ride out the days, weeks, months, and years until tragedy strikes and you need them. It is best to keep some chlorine on hand, though, in case something goes wrong. Remember, without water, you’re without life. Store it liberally.

SAFE PLASTICS

It is a common myth that water stored in polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles leaches Bis(2-ethylhexyl) adipate (DEHA) into the water over time (or exposure to heat or cold). Bottles made from PET do not contain DEHA, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Though Bisphenol A (BPA) is an issue. Make sure the containers you use to store water for long term are BPA-free. However, the truth of the matter is this: If you’re thirsty enough, you’ll boil rainwater found in the gutter or squeeze it out of a rainsoaked towel before succumbing to dehydration. You can choose: Die from thirst or drink water that may cause a hormone disrupter over long periods of time (such as BPA).

Where to Find Emergency Water in Your Home

Between the time you read this article to the time you have a fully-sustainable water storage system in place that will properly provide for your entire family, catastrophe may strike. What to do? First order of business, as long as your house and property are safe and secure (turn off the gas valve, etc.), fill your bathtubs with water. If it is an earthquake or flood, the first things to go are city services. Get the water out of your pipes and into a container before the pressure drops off. Baring that, there are several other sources of water in and around your house that you might overlook:

Hot Water Heater: Depending on your model’s capacity, there might be upwards of 80 gallons of completely fresh water waiting for you to tap into. Most water heaters have drain valves that can be opened to empty its contents.

Toilet Tank: The water in the top tank of your toilet is perfectly safe to drink, as it is water directly from the tap. After an emergency, it is a great source for a couple of gallons of water.

Fish Tank: After you eat the fish, filter the water, purify it, and drink it. A 20-gallon fish tank will provide water for a single person for over three weeks… not to mention all of that Omega-3 oil from the fish. Pool: If you have a decent sized pool, there is around 15,000 gallons of water waiting to be used. The problem is, as soon as the pumps turn off and the chlorine burns away in the sun, the water will become a breeding ground for algae and bacteria. Also, it is uncovered, which means any sort of contamination can (and will) fall in there. After that, the water will have to be filtered and purified.

Water Pipes: There is always water in your pipes. Most will have drained out after the pressure drops, but in some places (check the attic), water will collect in low spots and can be reached by disconnecting the pipes.

Liquid from Canned Goods: Peas, carrots, and other vegetables are usually packed in water to help keep them fresh. Don’t dispose of that water. Save it.

Defrosting Freezer: Your freezer might contain a lot of built-up ice that will soon begin to melt when the power goes out. Find a way to capture it. As well, check the tray underneath for runoff. There won’t be much, but every little bit counts.

Editor’s Note: A version of this article first appeared in the August 2015 print issue of American Survival Guide.