When you live out in the country, the local flea market caters to a whole different clientele, and preppers and survivalists can rejoice at the selection of cheap power tools, live chickens and random food that just “fell off the back of the truck.”

However, even I am occasionally surprised by what I find. Recently, one enterprising soul who works in construction was selling a sizable collection of ornate and rather large cast iron furnace doors, along with genuine 1962 emergency Office of Civil Defense/Department of Defense survival supplies.

He had dozens of 17.5-gallon steel water barrels, which were originally equipped with double plastic bag liners (the Defense Department bought 10 million of these for storing water in bomb shelters across America), as well as a selection of emergency fuel in steel cans.

What intrigued me the most, however, were the cases upon cases of 54-year-old “survival biscuits.” Were they still edible? I realized that a bit of a history lesson might be in order for those of us without one foot in the grave already.

GOVERNMENT-ISSUE SURVIVAL “CUISINE”

Back at the start of the United States’s involvement in World War I, Congress created the Council of National Defense to help organize civilian resources in support of national defense. By the start of World War II, the Office of Civilian Defense (CD) was established to again coordinate civilian resources and volunteers. (Many of you might be familiar with the white “doughboy” helmets worn by some volunteers, as well as the emblem of red “CD” letters inside a white triangle surrounded by a blue circle proudly displayed on the front.)

Later, the advent of the Cold War and the threat of toe-to-toe thermonuclear combat with the Russians again changed the mission of the CD: Once it became obvious that hiding under your school desk was not going to protect you from a nuke, the Department of Defense and the CD coordinated efforts to turn basements in buildings across the country into fallout shelters and to properly supply them for a minimum of a two-week underground “staycation.”

To keep people from leaving early, they stuffed the shelters with food, water and emergency supplies they knew would survive the test of time. It was from one of these abandoned and forgotten shelters in the basement of a building scheduled to be demolished that my enterprising flea market acquaintance had liberated the supplies he was selling.

While the food supplies were marked “biscuits,” they are actually crackers similar to saltines. Each sealed tin contains 434 biscuits, and one cardboard box holds two tins. According to the Cold War Era Civil Defense Museum, each “shelteree” was provided with 10,000 calories in crackers for the entirety of their two-week sojourn, or slightly more than 700 calories per day. I assume people were much thicker-skinned back then, because the idea of spending two weeks in a hole with starvation rations of water and crackers makes me want to go outside and play in the radioactive dust.

People (not me) have opened these cases in the past and sampled the goods. The consensus seems to be that they taste terrible but that they’re better than starving.

There is some precedence for this in the form of a food item called “hardtack.” This simple flour, water and salt cracker has been around since before Roman times. It is baked dry for long-term storage and transport. It was a staple of Union troops during the Civil War, and some of those rations had been around since the Mexican-American War, which ended more than 13 years earlier! Likewise, American troops got to enjoy Civil War-era surplus hardtack 33 years later during the Spanish-American War.

CAN YOU OR CAN’T YOU?

So, if Civil Defense crackers can still be edible when they’re some 60 years old, what about other things, such as canned foods? The answer is, “Yes”— and for a surprisingly long time.

The fact is, expiration dates on canned foods are grossly pessimistic estimates of when the food contained inside might start to taste less fresh than a new can of food, and the dates do not indicate when the food will go bad. The secret of preserved canned food is more than 200 years old and involves heating the sealed cans long enough so that all the bacteria inside are killed. Thus, the food cannot go bad—as long as the can remains intact and the food had no bacteria in it when it was canned.

In 1974, canned food recovered from a riverboat that sank in 1868 was tested by the National Food Processors Association (NFPA) to look for any bacteria, as well as to study the nutritional value that remained. The cans contained fruits, vegetables and oysters. The chemists found zero bacteria. Nutritionally, there was a significant loss of vitamins A and C, but the protein and calcium levels were normal. As for taste, I assume they could find no volunteers, so we’ll never know.

In another test, NFPA chemists opened a can of corn that had been stored for 40 years. They found that it was as fresh as a new can of corn.

The key in these examples is that the cans were not damaged. You would think that meats might not do as well as vegetables—but, again, you would be wrong. Canned meats actually do better than vegetables and keep their nutritional content and consistency longer. Some canned vegetables also tend to do better than others. Tomatoes and other highly acidic vegetables are naturally antibiotic. Bee honey also cannot go bad because of its low moisture content and high acidity. Honey found in 5,000-year old tombs is still good to go (note: Do not give honey to infants under 1 year of age). This is also the secret behind freeze-dried foods: No moisture means no opportunity for bacteria to grow and spoil the food.

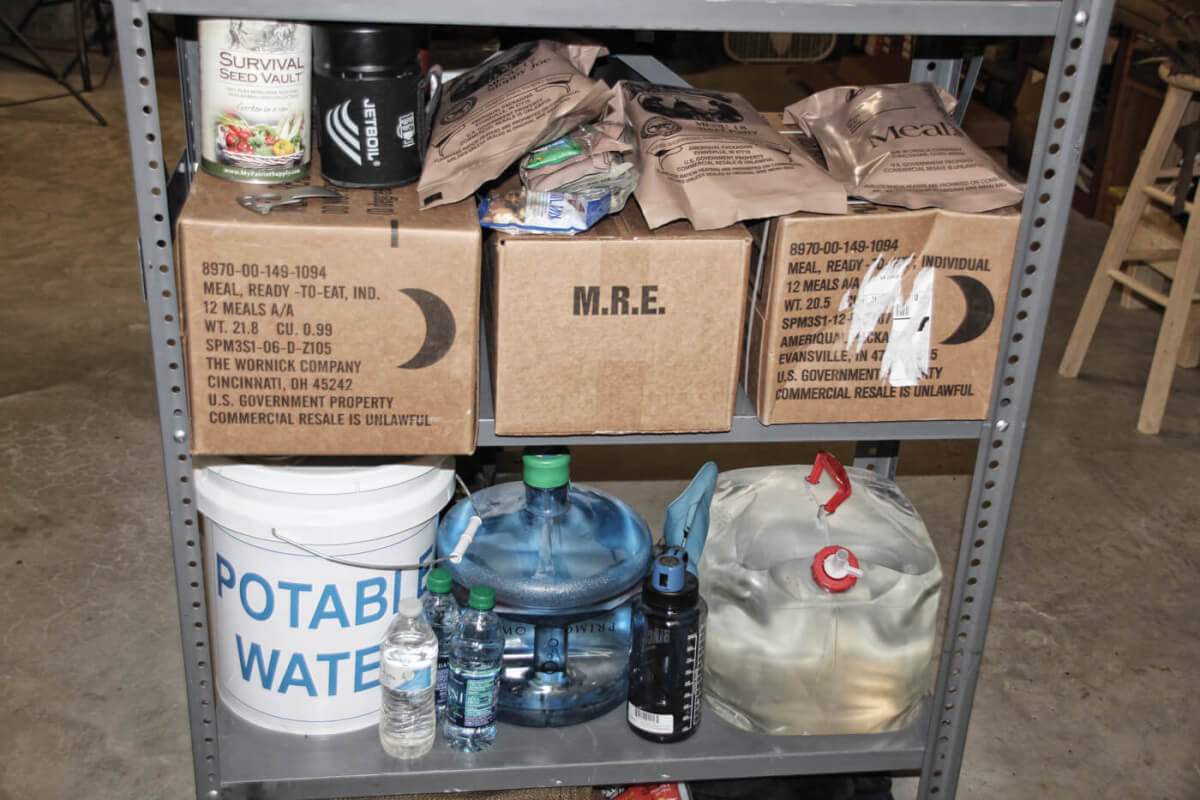

These basic supplies are a good start for a contemporary survival kit. Modern MRE rations have shorter shelf lives than canned rations, so be sure to follow storage recommendations for best results.

FINAL WORD

The final word of wisdom here is about storage conditions. Canned food that has been kept in a high-temperature and high-humidity environment for long-term storage is more likely to break down faster. Subjecting canned food to fluctuations of temperature and humidity extremes is also not a good thing. These conditions might cause damage to the cans—in which case, all bets are off. (Does this remind you of Grandma’s root cellar?)

While food canned today and properly stored can be counted on to provide nourishment and satisfaction for years into the future, it is good practice to rotate stocks to ensure flavor, as well as less concern about safety and compatibility with your latest food preferences.

Because there is no way to know how very old food has been stored, make sure to check any cans for damage or distortion of their shape before opening. The lids of food cans should generally be flat or slightly concave. Food from cans with ends that are bulged outward should be inspected closely before consumption, because the bulge is usually caused by bacteria.

As with with guns and ammo, store your food in a cool, dry place. Future generations could be counting on you!

Editor’s note: A version of this article first appeared in the January 2017 print issue of American Survival Guide.