Critical insights from everyone’s favorite survival MEDIC

Everyone has their favorite items they wouldn’t want to be without in a long-term survival scenario.

When an interviewer asks what pieces of equipment are must-haves, I immediately start asking questions: What’s the scenario—an economic collapse, a high-death-rate pandemic, a thermonuclear war? Are they staying in place or getting ouat of Dodge? Are they alone, with their family or in a survival group? Are there kids? Are there old folks? Sometimes, the questioner regrets having asked, but the answers to my questions factor into what you’ll need.

I don’t claim to be a bushcraft expert (my mission is medical), so my personal requirements might be different from others who wouldn’t be responsible for the health of a survival community.

In this article, though, I’ll discuss the items and skills that I’ve worked to obtain and hone in order to succeed when everything else fails. I’ll sometimes mention a brand name, but everyone is different, and their gear preferences should be the result of their own research and conclusions.

To begin, it’s worthwhile to review the famous “Rule of Threes”: You can survive three minutes without air before losing consciousness, three hours without shelter in harsh environments, three days without water and three weeks without food. Note that there are many exceptions to these rules. (For example, the record for going without air was set by a free diver in 2009: 11 minutes, 35 seconds. But you get the picture.)

SHELTER

Let’s say you’re not bugging out to the bottom of the ocean, so air is in abundance. However, you’ll need shelter.

A sturdy, defensible structure such as a house is the best option. The safest retreats are away from normal traffic patterns and have a clear zone surrounding them that would make the approach of others easy to notice.

On the road, you’ll need the skills to build a shelter or assemble a solid tent. Tents should be placed in the shade to avoid the deterioration that comes from exposure to the sun and bad weather. For me, the size would depend on the amount of time I’m spending in any one place and the amount of time I’m spending inside the tent. For comfort, consider allotting 20 square feet per person (although you can survive with a lot less).

A 10×12-foot tent will fit six sleeping bags (but fewer cots, because you need more space to get in and out). Most tents that size will have enough head room, lack of which can be an issue for those required to spend a lot of time inside. (Speaking of sleeping bags, I have the standard rectangular design, because it allows for more movement and comfort. “Mummy” bags are better in colder weather than is experienced here, in south Florida.)

For sleep only, single-person tents might be preferable on the road. In any case, they should have a floor and screening that’ll keep out the creepy-crawlies.

I currently have a 14×10 Coleman Instant Cabin, a 13×16 canvas Elk Mountain (These will do double duty as hospital tents for a group) and a couple of 10×10 canopies. I also have large tarps, rope and paracord that can serve to improvise shelters. These are easier for travel purposes but require skill to incorporate into solid protection against the elements.

WATER

Needless to say, you need a water source. Down here, in Florida, that isn’t a big problem, but disinfection of water is.

You’ll need reliable ways to filter water and get rid of the disease-causing organisms that live in it. The Civil War taught us that more deaths will occur from contaminated water and food off the grid than bullets and shrapnel. Learning how to disinfect and filter water properly can save your life.

Some quality water filters are very lightweight, such as the Sawyer Mini and the LifeStraw. Others are less portable but are of high quality, such as the Big Berkey. Our family has all these.

Low-tech disinfection options include boiling the water, liquid household bleach and solid calcium hypochlorite pool products that can be converted into a chlorine solution. Even so, a filter is still needed to remove particulates.

For those without ready water sources, water storage containers are very important. These come in sizes that range from 3 to more than 160 gallons. For portability, the 3-gallon containers from WaterBrick and AquaBrick stack easily. The larger containers can be found at Water Prepared (many are also stackable and come with spigots).

FOOD

A sign of the times is that there are now ads for emergency food supplies on major television channels. But nothing beats having a working garden; and for those who haven’t started one, be aware that there’s a learning curve.

Once you’ve got a productive vegetable garden, there might be more food at harvest than you can consume. Our family has a pressure canner and an Excalibur dehydrator that’ll help keep surpluses edible through a long, hard winter.

Even those with “green thumbs” want variety and comfort foods. Having a good quantity (at least several months’ to a year’s supply) and variety of long-shelf-life foods will make life easier if things “go south.” My family’s plan is to “bug in” and have a ready water source; as a result, freeze-dried foods in #10 cans are our main long-term supply.

Besides water for food preparation, you’ll need a heat source, so having a reliable method to make fire is imperative. We have several different fire-starters and, dare I admit it, two boxes of 50 BIC lighters … each.

We keep a limited amount of MREs (“meals, ready-to-eat”) in case we’re forced to bug out on foot. They’re convenient but relatively heavy. As a result, more than a few, and you’ve got a lot of weight in your pack. You should also know that eating MREs for more than three weeks in a row could give you a nasty case of constipation. Also, their shelf lives suffer in hot weather if the power’s out.

Don’t forget the cookware. “Cookset” items, such as our hard-anodized aluminum GSI Pinnacle Dualist, are made to nest within each other like Russian dolls, making transport easier. They’re relatively lightweight, scratch- and dent-resistant, and conduct heat well, which cooks food more evenly.

The largest pot should hold about 1 pint per group member. You might get away with just one pot if you’re only cooking for two people. Lids help cooking go faster, save fuel and reduce splatter. (My wife prefers cast iron—but don’t ask me to carry or maintain it!) Additionally, don’t forget utensils and, for safety with campfires, pot lifters or grippers.

For fireless cooking, we have a Sun Oven that’s good for use in sunny weather and even helps disinfect water.

CLOTHING

You need the right clothes for the local climate. In South Florida, wearing a parka is a ticket to a case of heat stroke. On the other hand, up in the “Great White North,” you can’t live without one.

Have enough changes of clothing so you can add or remove them based on the weather. There’s some warm air between each layer—an advantage in cold weather.

Make sure you have good hiking boots that are well broken-in, as well as wool-blend socks and synthetic liners, so you can avoid the inevitable blisters many get when on the road. I won’t mention brands here; everyone’s feet are different. What works for my wife doesn’t work for me (and might not work for you).

When buying new boots, be sure to try them on in person and at the end of the day, when your feet are most swollen.

I also make sure to have (and use) protective eyewear and gloves for work sessions.

KNIVES

The best survival knives can be used to perform many tasks, from slicing an apple to gutting a deer. Fixed-blade knives allow cleaning off grime that would render a folding knife difficult to maintain. Most good fixed blades are “full tang,” which means the blade’s steel runs the full length of the knife. This makes them stronger and more durable. A folding knife, however, is fine for lighter tasks.

For working with wood other than kindling, I prefer a hatchet or a good, strong axe. I use a Schrade Old Timer hatchet/gut hook knife combo, because it’s easy to carry and does the job. Among quite a few other edged tools, my favorites are the Gerber Gator Machete JR and SOG SEAL Pup field knife. SOG also makes a great multi-tool, and Schrade has a good, folding, sharp-edged shovel. In addition, don’t forget to include a whetstone to keep your sharp edges sharp.

POWER

Any permanent-structure retreat needs a power source, and a gas generator will be a great option in the early going when fuel is still available. Once you’re truly off the grid, solar power is king.

Our solar panels can be “daisy-chained” to each other and then connected to 12-volt marine batteries for power storage. A PowerBright inverter and cable are then used to access that power. On the other hand, the disadvantage is the weight involved with marine batteries.

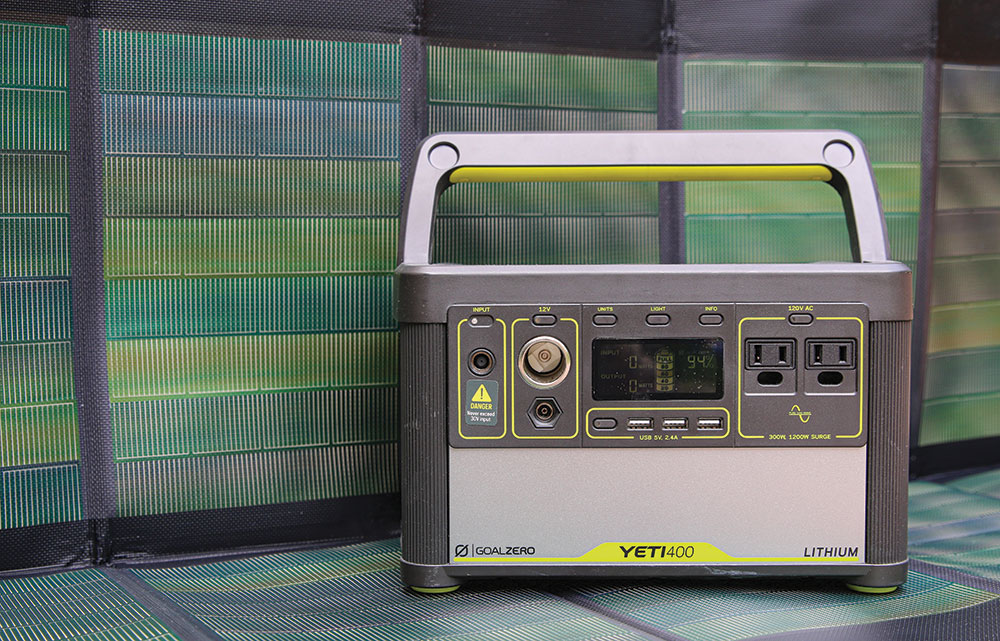

A portable option is the YETI 400 LITHIUM power station by Goal Zero. Solar panels collect power and transfer it through cables to the YETI; you then just plug in whatever needs “juice” (including rechargeable batteries—another important item to have in your storage).

LIGHT

When it’s winter and your daylight hours are, therefore, limited, you’ll appreciate having a number of different light sources. I have a multitude of these, ranging from solar or battery lanterns to flashlights, glowsticks, oil lamps, candles and more. Some of the lanterns even work with hand cranks.

Our main flashlight is a Feit Electric ultra-bright, 750 lumen LED constructed from durable, aircraft-grade aluminum alloy that’s treated to prevent rust and corrosion. Is it weather-resistant? Well, it’s submersible up to 26 feet.

It’s important to realize that injuries can occur at night. A headlamp will give the group medic two free hands with which to handle the emergency.

I have more than I can count, but my favorite might be the Biolite 330. It’s very bright and has multiple modes, including “spot,” “flood,” “spot and flood,” “strobe” and red “night vision.” It can be set at several angles, and the light output lasts a long time on a single charge (40 hours when dimmed; 3.5 hours on high).

COMMUNICATIONS

Both my wife and I have ham radio technician’s licenses. Being able to use radios to communicate is an important skill to have.

While we don’t have an elaborate setup, we both have ICOM T70A transceivers. The benefit is an amplifier that doubles the audio output, making conversations easier to understand. The ICOM is lightweight and offers up to 19 hours of operating time.

“Get as many supplies as you can afford, because you’ll expend them quicker than you expect.”

We also have a Midland XT511 Base Camp two-way radio with emergency crank power. It has GMRS/FRS, NOAA weather and AM/FM bands—plus a bright, LED flashlight. It’s compact, lightweight and works with AA batteries or the rechargeable battery pack that comes with it. The two-way function has a range of two to three miles and comes with a speaker mic and a built-in speaker. A USB port is included to charge a cell phone with the battery or the crank.

NAVIGATION

We’re all spoiled with the availability of GPS these days, but off the grid, you’ll need a reliable compass, some detailed maps of the area … and the knowledge needed to use them.

PERSONAL DEFENSE

I’ll leave this one to you. My job is to heal wounds, not make them. Just be sure you have ways to defend yourself, because in a long-term disaster, it’ll soon become clear that you’re healthy and well-fed when the rest of the area is starving and sick. That means you’ve got food and other supplies that desperate people will do anything to get.

MEDICAL

Your people will be performing tasks to which they’re not accustomed, so expect injuries such as cuts, bruises and burns. Consequently, a good medical kit is a necessity. Because I’m a physician and my wife’s a nurse practitioner, our medical supplies are enough for a small field hospital. Yours should, at least, contain the following items:

- Military-style tourniquets (C-A-T, SOF, SAM XT)

- SWAT-T elastic band tourniquets (good to stop bleeding but versatile enough to serve as a compression dressing, sling, stabilizer for splints, etc.)

- Hemostatic (blood-clotting) dressings (QuikClot, ChitoSAM)

- A wide variety of gauze and other rolls and pads ranging from 2×2 inches to 10×30 inches for bandaging, packing and dressing wounds. Especially consider a supply of versatile triangular bandages.

- Medical tape

- Burn dressings (usually a non-adherent dressing impregnated with substances to speed healing)

- Compression dressings such as the Emergency Bandage (sometimes known as the “Israeli Battle Dressing”)

- SAM Splints (up to 36 inches of multiuse, malleable structural aluminum that can be cut to order for various injuries)

- Elastic (ACE) wraps for sprains and strains and to secure splints in place

- Moleskin, 2nd Skin or duct tape for blisters

- Antiseptics such as chlorhexidine (Hibiclens) and povidone-iodine (Betadine)

- Masks and gloves

- Wound-closure supplies (sutures, staples, glues and 3M Steri-Strips; duct tape can make butterfly closures.)

- Pain meds such as ibuprofen and acetaminophen; diarrhea and constipation meds; vitamins

- Prescription drugs, as needed by individual group members

- Antibiotics for infection (I’ve written many times about some commercially available “fish” equivalents as last resorts for long-term survival. This is frowned upon by the medical establishment but might save a life if there isn’t a functioning medical infrastructure). At least have some antibiotic cream or ointment.

- Dental kit to deal with issues in prolonged survival scenarios

Notice that I haven’t mentioned the quantity of the above items you’ll need. This’ll depend on the number of people in your group, the terrain difficulty, weather and the nearby presence of hostile groups. Get as many supplies as you can afford, because you’ll expend them quicker than you expect.

Of course, medical supplies are of little use if you haven’t learned how and when to use them. For instance, having a tourniquet without knowing how to apply it is of little help.

Obtain whatever medical training you can get. I’ve taught suturing for many years as a fellow of the American College of Surgeons, and I can tell you that closing the wrong wound can lock in bacteria and cause serious infections. Work to develop not only the skills, but also the judgment, needed to be the group medic. If you don’t, who will?

(For a discussion and demonstration of important supplies, see the first of a series of videos made by Nurse Practitioner Amy Alton here: youtube.com/watch?v=snumqufPtBQ)

A version of this article first appeared in the September 2021 print issue of American Outdoor Guide.