Are You Prepared to Get Back Home on Foot if Your Vehicle Breaks Down?

Mike Tyson once said that everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face. He had one thing right: No plan ever survives the first round fired.

“Murphy’s Law” states that everything that can go wrong will go wrong at the absolutely most inopportune time. That might be true, but having a plan to start with is always better than no plan at all. Even if your plan falls short, at least you’ll have some basic idea of what to do if things go south.

It’s virtually impossible to be 100 percent prepared for every contingency or emergency situation you might find yourself in, but you can drastically increase your odds of survival by personalizing your survival strategy and plans to your own personal biorhythm.

TRAVELING ON FOOT

When you look at this from a worst-case-scenario perspective, you need to assume that for whatever reason, your vehicle will be rendered inoperable, and you’ll have to depend on your ability to walk to wherever you decide to go. This doesn’t mean you don’t have to plan for contingencies for which you might be able to get the vehicle operational again; it’s just that you always need to plan to walk in the event that riding is no longer an option.

People can, have and will resort to extreme violence when they’re scared, hungry or when they believe there will be no repercussions for their actions. As Ronald Reagan liked to say, “Trust, but verify.” You should assume everyone is a potential threat until you can verify that they aren’t.

Predators often prey on the goodwill of others and will, no doubt, take advantage of chaos to benefit themselves. So, keep your head on a swivel, and stay alert. In addition, having a base distance in mind will help you choose the survival gear you should carry with you when you leave home.

If your work is a five-minute walk from your home, you probably don’t need to carry a 100-pound pack of supplies and gear with you every time you walk to the office. On the other hand, if your commute to work is an hour or more drive from your home, it could take several days to weeks to walk home, depending on the situation.

GBH DISTANCE

How far you can move on foot per day is subject to many variables, such as what shape you’re in, how tough your feet are, the footwear you have on, the terrain, weather, threat situation … the list can go on and on.

As a rule of thumb, you should plan for five to 10 miles a day. Avoiding obstacles and people whenever possible will slow you down considerably—but slowly and deliberately is better than carelessly and full-speed-ahead, particularly when the emergency situation is still an unknown factor.

It’s probably safe to say that in an emergency, the vast majority of us would be compelled to, at least in the interim, return to our homes to check on loved ones and assess options moving forward. Think about the farthest point from your home you generally travel each day for work, shopping, appointments, etc., and come up with a maximum distance to use as your base number to begin your personalized “GBH,” or “get back home plan.”

Example: The driving route distance from home to work is 25 miles. If your drive to and from work is the farthest distance out that you travel in a day, your GBH distance equals 25 miles. Assuming you’re able to travel 10 miles per day on foot with a backpack over even terrain, you should be able to make it home in 2.5 days. Always rounding up, you’d want to have three days of food and water with you at any given time.

This is just a rule of thumb. The distance could be much longer in the event that you need to take a longer, alternate route or travel cross-country to avoid obstacles—or, potentially, people.

‘PACE’

“PACE” stands for “primary, alternate, contingency and emergency.” PACE is an acronym commonly used by the military as a tool to put to memory a series of plans and contingency plans that help ensure there are multiple options to choose from, depending on the situation.

“There have been too many survival scenarios that started out as a vehicle road trip but simply went bad somewhere along the way.”

Remember: Emergency situations can be highly fluid, and knowing when to stop what you’re doing and refocus on something completely different can be a difficult thing to do. When indications to change course are ignored is when people run into problems. You can apply PACE to all your plans and contingencies in order to maximize your chances of survival, no matter the situation.

While everyone’s situation is going to need to be planned for differently, there are many planning considerations that will be common to most scenarios. So, planning and preparing for those commonalities will be a great place to start.

Here’s a generic contingency packing list of items you can keep in your personally owned vehicle in preparation for an unknown future survival situation. You always have the option of taking away from, or adding to, this contingency list based on the time of year, terrain and known threat situation. You’ll want to plan your contingencies on your maximum GBH distance and use the worst-case scenario of foot movement as your means of transportation for planning purposes.

EMERGENCY CONTINGENCY PLAN VEHICLE PACKING LIST

Food: Keep enough extended-shelf-life meals in your vehicle to give you 4,500 to 5,000 calories per day times the number of days it’ll take you to move on foot from your maximum GBH distance.

Water: You should keep a minimum of 1 to 2 gallons of water per day times the number of days it’ll take you to move on foot from your maximum GBH distance. You should also keep a personal water filtration device in your vehicle in case your GBH distance exceeds your ability to carry enough water in your pack to get you all the way home.

Shelter: Keep a small, well-constructed tent in your vehicle to provide you with shelter in case you have to leave your vehicle and move on foot. Consider purchasing a brightly colored tent that can be easily identified by rescue personnel. And don’t forget to include a wool blanket or a sleeping bag.

A poncho and poncho liner give you multiple options, including shelter, warmth and light discipline, as well as the ability to camouflage yourself, your tent and your gear.

Clothing: Keep weather-/climate-appropriate shoes and socks in your kit. You should have shoes that are broken in and provide a proper fit. You’ll also want to have several pairs of high-quality hiking socks.

Security: As long as you’re properly trained to use a firearm—and you’re legally permitted to carry one—it only makes sense to do so in today’s volatile world. The only time carrying a firearm isn’t a smart idea is when you either can’t due to legal restrictions or when you’re not competent in employing a firearm to protect yourself or others. Remember: Once a bullet leaves the barrel of a firearm, there’s no calling it back. Consequently, it’s imperative to be able to fire it accurately so you can hit your intended target without any collateral damage.

Pepper spray, stun guns, billy clubs and other, less-than-lethal tools are all excellent to keep in your vehicle in the event of an emergency. However, much as with firearms, it makes no good sense to have these tools if you aren’t adept at using them under stress … because they can easily be turned against you.

Communications: Having a hand-cranked AM, FM and Weather Emergency Radio will give you the ability to monitor local news for search party information, as well as other emergency alert guidance.

CB radios give you the ability to possibly get the attention of a trucker or another person monitoring your frequency to relay your emergency situation to the authorities. But, if all you have is a cell phone, and voice calling doesn’t work, try text messaging, because they work on totally different systems and frequencies. Texts typically work much longer than voice, because text messages use comparatively little bandwidth. (In any emergency, be sure to turn down your screen brightness, put your phone in “battery save” mode, and disable Wi-Fi to conserve battery life.)

Alternatively, a ground-to-air marking panel comprises contrasting bold colors on opposite sides of the panel that can be used to bring attention to your location from the air. Finally, flares are a good, last-mile signal that works day or night. Because they can be fired quickly, they’re useful for signaling others who might not be in view for very long. Don’t waste them if an aircraft is flying away from you.

Health: Assemble a comprehensive, personal first aid kit that’s fully stocked at all times. Include an emergency first aid manual as well.

Vehicle Preparedness: Consider a vehicle kit that contain the following items:

- Emergency signal panel

- Road flares

- Reflective triangle

- Jumper cables/automatic jump-start device

- Fix-a-Flat

- Small air compressor

- Tow strap or cable

- Spare tire

- Tire jack with lug wrench

- Tire traction straps or chains

- Spare parts (belts, hoses, fuses, fluids)

- Folding shovel

- Ice scraper

- Local road maps and GPS

- Flashlight

- Assorted hand tools

ALTERNATIVE MEANS OF TRAVEL

While most people in America do the majority of their day-to-day travel from point A to point B, either in a personally owned vehicle, via public transportation or on foot, there are certainly those who chose alternative means—bicycles, scooters, skateboards and many other transportation platforms.

Lithium-ion battery technology has made some huge leaps over the past decade, and you can now purchase a number of electrically propelled, as well as electrically assisted, systems that can be recharged with the power of the sun and that could easily break down to fit into the trunk of an average car.

“How far you can move on foot per day is subject to many variables, such as what shape you’re in, how tough your feet are, the footwear you have on, the terrain, weather, threat situation … the list can go on and on.”

Keeping one of these folding electric bikes or scooters in your vehicle to use as an alternative to walking is an excellent contingency plan in the event your vehicle becomes inoperable. Many of these platforms are small enough to be hand carried when you take public transportation.

Anytime road travel is an option, having something with wheels will almost always be an advantage, as opposed to having to walk, particularly when time and fatigue are factors. If you drive a truck, getting into the habit of traveling with an old bicycle in the truck bed is also a great idea for an alternative means of transportation in the event of an emergency.

There have been too many survival scenarios that started out as a vehicle road trip but simply went bad somewhere along the way. Natural circumstances, such as inclement weather and poor preparation—such as not having sufficient food, water, clothing or gear in the vehicle—can all be contributing factors, as well as poor planning, getting lost or simply having bad luck.

The best way to make sure your next road trip doesn’t make the 5 o’clock news is to dedicate time to prepare yourself and your vehicle for emergencies, particularly when traveling through unknown or sparsely populated areas.

By understanding the GBH distance and the terrain you might have to navigate in a worst-case scenario, you can mitigate the risks of becoming just another statistic when an emergency or disaster strikes.

TAILOR THIS ‘PACE’ PLAN TO YOUR SPECIFIC NEEDS

Use the example of a PACE plan below, and then tailor a plan that fits your own personal level of preparedness.

GBH Bag Contents Note: This PACE plan is based on the assumption that the survivor is dressed appropriately for the outside weather conditions and that they have their GBH bag and personally owned vehicle with them.

Food

P: 6x MRE (“meals ready to eat”) main meals

A: 6x 500-calorie power bars with your EDC (break-away satchel bag)

C: SDS Imports Lynx LH-12 shotgun and U.S. Survival AR-7 .22 LR rifle

E: Field-expedient items (survival knife and survival kit for hunting, trapping/snaring, fishing, gathering)

Water

P: 3-quart water bladder and two 2-quart Nalgene bottles

A: Water filtration system (such as Lifestraw)

C: Alternative purification methods (UV, iodine, bleach)

E: Field-expedient method (boil, field-expedient filter, rainwater catch)

Shelter

P: Clothing/gear/walking shoes (seasonal)

A: Tent/poncho shelter

C: Mylar blanket/survival shelter

E: Field-expedient method (debris hut, swamp bed, snow cave, etc.)

Security

P: SDS Imports Lynx LH-12 shotgun and U.S. Survival AR-7 .22 LR rifle

A: Beretta PX4 storm-type F 9mm pistol

C: Taser/stun gun and mace/pepper spray

E: Full-tang, 7-inch-plus survival knife, hands … and your brain

Communication

P: Cell phone/satellite phone

A: CB radio

C: Road flares, smoke grenades, fireworks, etc.

E: Personal locator beacon, survival radio and field-expedient signaling (i.e., smoke signals, mirror, ground symbols/panels, etc.)

Health and First Aid

P: Individual first aid kit

A: Prescribed medications and preventative medicine procedures

C: Nuclear, biological and chemical protective mask, field-expedient protective measures, NBC decontamination kit

E: Field-expedient medicine (i.e., medicinal use of plants, home remedies, survival medicine techniques)

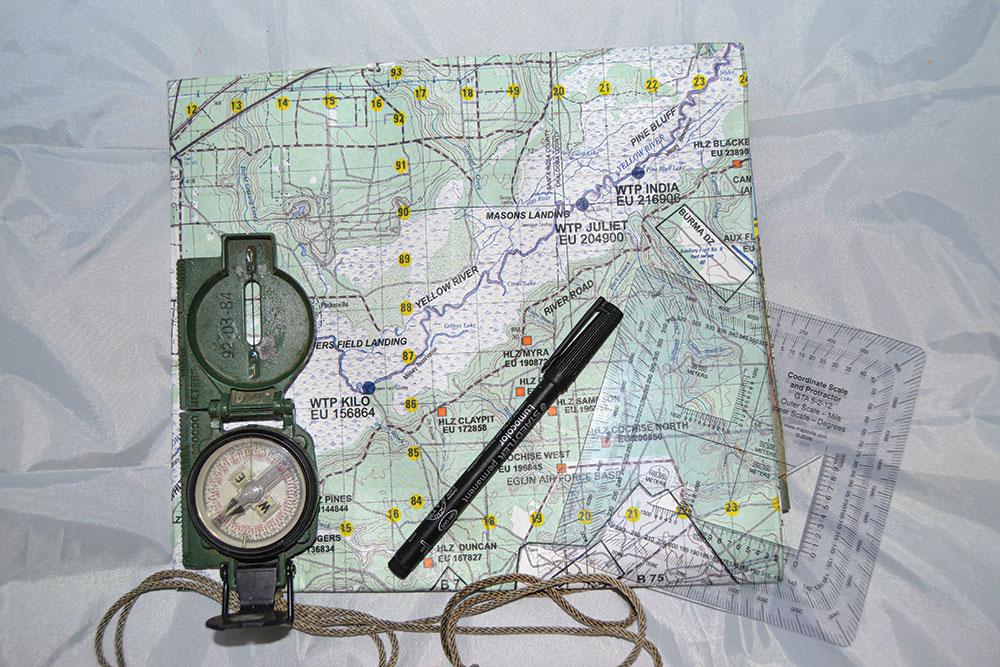

Land Navigation

P: GPS

A: 1:50,000 map (or other comparable hiking map or road atlas), lensatic compass, protractor, pace beads and map pen

C: Button compass

E: Field-expedient direction-finding techniques

Firecraft

P: Lighter

A: Road flare

C: Solid fuel tabs, magnesium bar, other commercial incendiaries

E: Field-expedient fire-starting techniques (friction fire, battery, magnifier, fire piston, etc. [All items should be in a firecraft kit in your GBH bag])

CONSIDER THESE ACRONYMS AS PART OF YOUR

Some good planning tools used in the military to plan for contingencies are the acronyms, OCOKA and METTC.

OCOKA

• Observation & Fields of Fire: This is how well you can see everything around you and how much visibility you would have in order to engage an enemy from a distance.

• Cover & Concealment: Cover is anything you can get beside, behind, inside of or under that will protect you from small-arms fire. Concealment is anything you can use to hide or mask your movement.

• Obstacles: Anything that either gets in your way or poses a potential threat to you is considered an obstacle.

• Key Terrain: Any terrain, whether it’s man-made or natural, is considered key terrain if it can potentially be an advantage or assist you in getting back home safely.

• Avenues of Approach: These could be highways, power lines or any line of communication that will help you get back home or avoid an obstacle on route.

METTC

• Mission: In your case, it’s to get back home.

• Enemy: Anyone or anything that could pose a threat to you

• Time: How long you have the means to survive

• Terrain: What type of terrain you’ll be traversing

• Civilians: To simplify: You can consider a “civilian” to be anyone who poses no immediate threat to you and who isn’t either military, law enforcement or a first responder whom you might encounter as you make your way back home.

A version of this article first appeared in the January 2022 issue of American Outdoor Guide Boundless.