Sometime around May 8, 1942, lost in Saharan Desert in Libya, Major J. L. V. de Wet of the 15th Squadron of the South African Air Force (SAAF) wrote in his diary:

“6 of us left — out of 12 — no water — we expect to be all gone today. Death will be welcome. We went through hell.”

The SAAF established the 15th Squadron in 1939 and it was used for maritime patrols. By 1941, it was reborn as a North African unit with the primary role of protecting ground troops in the North African campaigns of World War II. The unit first camped at Amariya near Alexandria, Egypt and was equipped with Blenheim MK IVs. Though the Blenheims were obsolete when it came to primary front line aircraft, they still could serve as combat support in North Africa where German and Italian air opposition would be minimal. Eventually, the unit would head south, via train and Nile River boat to Wadi Haifa where a group would break off and trek northwest, through the unflinching, brutal Sahara Desert of Western Egypt and Eastern Libya. Almost a month earlier, on April 17, 1942, SAAF mechanic Gerald Mostert wrote in his diary of their first day on the road to Kufra:

“Say goodbye to Wadi. Leave in convoy at 16:00 hrs. Do 20 miles & make camp after losing the convoy & nearly getting lost…. Extreme temp – in shade today 110°.”

They would finally reach the small oasis of Kufra a week later after covering nearly 630 miles of desert emptiness.

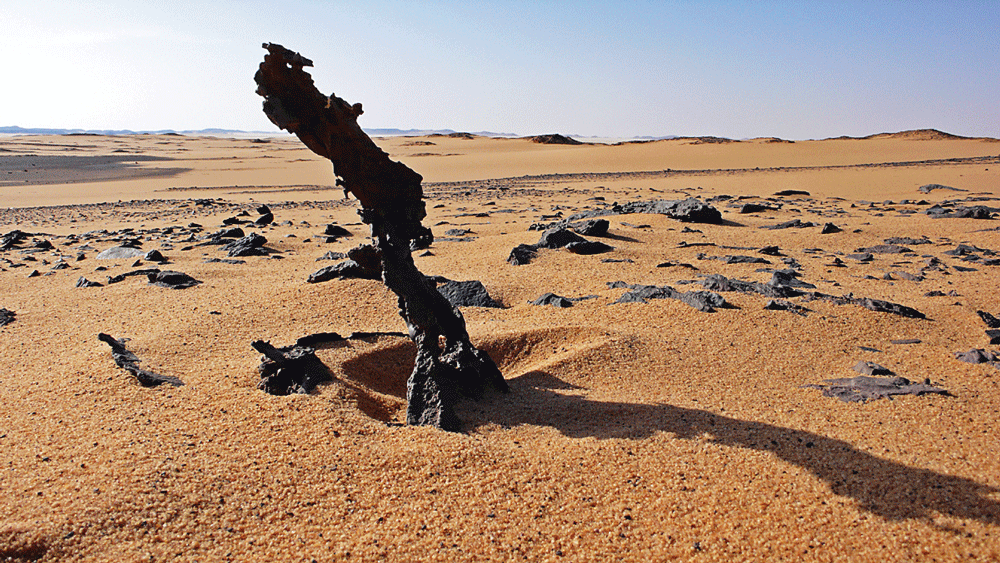

UNFORGIVING DESERT

The Sahara surrounding Kufra is a harsh and forbidding land that renders a brutal punishment on the foolhardy, inexperienced, and naïve. And it was into this environment, devoid of human habitation save the small Senussi tribal village of Kufra (turned into a refueling base by the Italians in the 1930s) that the 15th Squadron of the SAAF sent three Blenheims, their crew, mechanics, and radio operators with only two members of the entire 15th having had any desert training or experience.

Problems plagued the 15th at Kufra from the start. When the three aircrews under the command of de Wet and their three Blenheims reached the airbase on April 28th they found that the radio Direction Finding (DF) station was not operating correctly. Despite this, the aircrews were able to land safely, but it was enough of a concern that Lt. Col. Borckenhagen ordered all aircraft grounded until the problem was fixed.

By the morning of May 3, the point-to-point radio station was deemed to be functioning properly. The radios on the aircraft were tested and all checked out. So the three Blenheims were fitted with fuel, oil and armaments for a familiarization flight the next day. Contrary to his orders, de Wet planned for all three aircraft — numbers Z7513, Z7610, and T2252 — to engage in the flight.

Each plane carried seven-and-ahalf gallons of fresh water and rations that could last four days. Additionally, each crewmember was assigned to carry two quarts of water.

The main objective for de Wet in getting all three aircrews flying was to acquaint the navigators and pilots with the region, get some desert flying experience for his crews, and allow for some training time in the air for his navigators.

The route would be nearly square and cover some 208 miles and a flight time of close to two hours.

Based on what followed, from both de Wet’s diary and the sole survivor Noel St. Malo Juul’s testimony at the Court of Inquiry later, de Wet would have been better off training his navigators on the ground at Kufra.

FLIGHT TIME

The three aircraft took off at 6 a.m. on May 4. The weather was good for flying and the take off was uneventful. The three planes flew at 1,200 feet and from a navigator’s log we know that the outside temperature hovered around 100 degrees F and was turbulent enough they were unable to record the drift readings. According to N St. M Juul’s testimony, the training run completed all their tasks and they returned to Kufra around 8:30. However, based on reports from the three waypoints along the way, the three SAAF planes were hopelessly off course from the start.

None of the three waypoints reported seeing or hearing the group at the times they were supposed to cross them. It is possible that the navigators and pilots aboard the aircraft assumed they recognized land features from maps and changed course to their next leg thinking they had reached their target points. Around 7:10, the radio post at Kufra heard from Z7610, piloted by 2nd Lt. J. H. Pienaar, requesting a bearing. Unfortunately, the navigator aboard did not send out the appropriate Morse code signal so no bearing could be ascertained.

At 7:27, de Wet’s plane was heard requesting a bearing, but, again, the appropriate dashes and dots were not transmitted. The station operators took snap bearings and responded, “120-3=0527” which meant for the planes to fly on a 120° heading, third class fix, 05h27m (GMT). From de Wet’s diary we know the only message his navigator heard was “3-0-5,” because he writes:

“On last leg (No. 7 to Cufra) D.F. gave course to steer 305 deg. On E.T.A. turned to 305 found lost so flew on 125.”

This was the beginning of the end for the men aboard the three aircraft.

LOST!

At some point, while they flew back on the 125 degree reciprocal heading, de Wet’s aircraft’s starboard engine cutout and he ordered all three planes to land. The pilots and navigators quickly got together and debated their location and all had different opinions.

One thing they did agree on was that they were no further than 20 miles from Kufra and that rescue would be imminent. In fact, they were more than 80 miles away and rescue would not come for eight days. What followed can only be described as a litany of what not to do in any survival situation.

DESERT HEAT

Under the intense desert sun the men found the heat to be unbearable and, either out of desperation or an assumption they’d be rescued soon, went through nearly all their water. In his testimony Juul said:

“We did not ration the water on the 4th May, and by the following morning had consumed nearly 20 gallons, when we decided to ration water.”

Had de Wet imposed the desert rations of 2.5 liters of water/day there would have been enough to last four days.

Back at Kufra, the garrison commander quickly realized the three Blenheims were down and lost. Search parties were organized at Kufra, Rebiana, Bzema and LG07, but no one had heard the aircraft on their original flight and all teams returned having found nothing.

In Amariya, Borckenhagen, hoping for better news the next day, delayed orders to send out search planes. On May 6, two Bombay Bristols left Wadi Haifa for Kufra, but from Gerald Mostert’s diary, we know that the planes could not land in Kufra because of a sandstorm; they force landed 40 miles south of the airbase.

“Have dust storm,” he wrote on May 7. “Still no news. Bombays return [to Wadi].”

To compound matters, the pilots of the Bombays did not know that the DF station in Kufra was operational, so they never attempted to make contact with the base.

LAST RATIONS

At the site of the three stranded aircraft, the situation deteriorated quickly. On May 6, de Wet issued the last 1.25 liters of water to each man (one small bottle).

“On the morning of the 6th we received our last ration,” Juul testified.

By now, the men already drank the oil from the sardine tins and the juice from the canned fruit. In desperation, de Wet had ordered search flights to be conducted. Two flights went out immediately on May 4, but returned disappointed. The next flight would occur on May 6, as Juul would testify:

“On the morning of the 6th May, 2/Lt. Pienaar decided to take off in Z.7513 and fly west as this was the only direction that has not been searched. He did not return. We were still trying to receive wireless messages without success.”

Apparently, fuel became an issue and the plane was forced to land some 30 miles to the north of the other stranded aircraft.

By the evening of May 6 a sandstorm swept through the site of the downed planes. With no shelter — other than climbing inside the aircraft and baking in the heat—the men were battered by the parching winds that not only dehydrated them, but also allowed static electricity to form and spark from one man to the other on the slightest contact. In this horrific environment the men went mad and began to do desperate things. De Wet’s diary explains:

“Still some water left. Broke compass for alcohol – it’s stimulating. Not so much heat as previous days – but one must have water.”

While “stimulating” in the short run, the long-term effects were disastrous. One man drank too much alcohol and shot himself because of the pain in his stomach.

But drinking the ethyl alcohol from the compasses was not the only poor decision the men made. As the sand storm intensified, they resorted to spraying themselves with the fire extinguishers to cool their bodies. Again, the relief was only momentary, and, soon, their skin erupted in blisters that ruptured and left their skin raw and exposed to the wind. By the end of May 6, three crewmembers were dead.

“It’s the 5th day, second without water and 5th in a temp. of well over 100,” de Wet wrote. “Boys are going mad wholesale – they want to shoot each other – very weak myself – will I be able to stop them and stop them from shooting me – Please give us strength.”

Despite the fact that a ground search was closing in on the location of the downed aircraft, the mood at the site had grown despondent. According to Juul, the men suggested to de Wet that he begin shooting “them as all hope of being found had been given up.”

LAST DIARY ENTRY

Somewhere around May 10 de Wet makes his last entry:

“Hope, Sgt. Vos and Lew also gone. Only me, Shipman and Juul left. we can last if help arrives soon – they know where we are but do not seem to do much about it. Bit of a poor show isnt it.”

What he did not know was that Z7513 had been found the day prior, but all three men were found lying in the shade of the wing, dead, probably from exposure and/or thirst. On May 11, Mostert notes in his diary:

“Kites [planes] go out early and the original Wimpi [a Vickers Wellington] finds the other two kites about 25 miles North of mine, in the form of a Vee. Juul was the only survivor – brought in and put in sick bay. So the sad fate of the ilfated [sic] lost patrol is established.”

The bodies of the 11 men who perished were buried at the crash sites by the rescue parties, but later exhumed and reburied at the Knightbridge Cemetery in Libya. The Court of Inquiry set the cause of the tragedy with the lack of experience and skills of the pilots and navigators and the escalation of the tragedy with the “(a) Failure at first to appreciate their plight. (b) Failure to ration their water immediately. (c) Unintelligent use of compass alcohol and fire extinguishers.”

Sweeping changes would follow, but all too late for the 11 men of the 15th Squadron SAAF.

Editor’s Note: A version of this article first appeared in the July 2015 print issue of American Survival Guide.