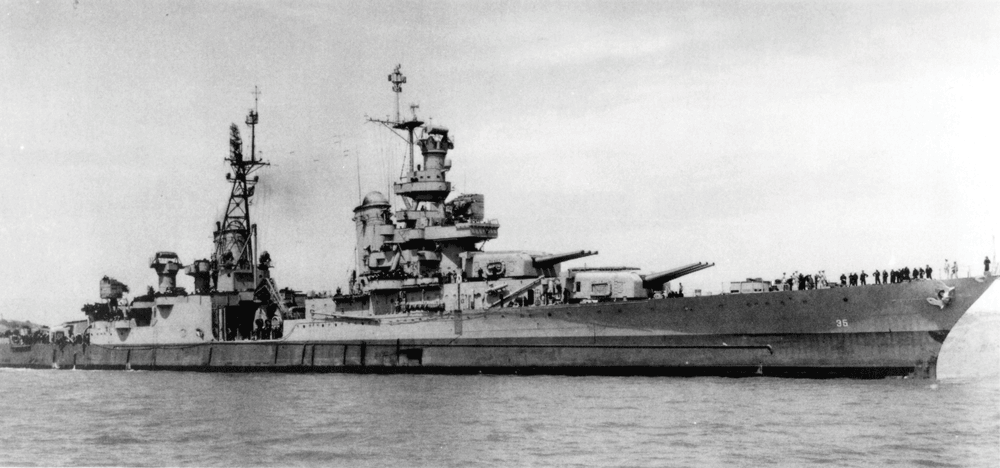

The USS Indianapolis was the pride of the American Navy. When she was launched in 1931, she epitomized the power, determination, and drive of American ingenuity and spirit. The Indy Maru, as she was affectionately called, represented the latest in naval and warfare technology. As a “treaty cruiser” — she was built under the terms of the Washington Naval Conferences of the 1920s — the Indianapolis, a Portland-class heavy cruiser, was 610 feet in length (half the height of the Empire State building, also completed in 1931) and 66 feet at the beam. Indy cruised at 32 knots and boasted nine 8-inch guns in three turrets. She was fast and she was powerful. She was America. So much so that President Franklin D. Roosevelt adopted the Indy as his official “Ship of State.”

US FLEET’S FLAGSHIP

In modern-day parlance, the USS Indianapolis was in every way a precursor to Air Force One. Roosevelt chose the Indy Maru as his official ship and used her on every transatlantic and South American cruise. She entertained royalty and other world leaders on her grand quarterdeck (a hallowed place reserved for admirals, captains and other dignitaries, and where enlisted men were not allowed to walk on the teakwood deck with shoes on). In 1936, the Indianapolis brought Roosevelt to South America on his Good Neighbor tour and eventually to Buenos Aires for the Pan American Conference.

She was a grand dame of ships, but she was also a warship, and in that capacity the Indianapolis served as the flagship for the Scouting Force, U.S. Fleet during the 1930s. As the ominously dark clouds of war loomed in the Pacific, the U.S. Navy was reorganized and, as a show of force toward the Japanese, the Fleet was moved from the West Coast to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The Indy followed and became Vice Admiral Wilson Brown’s flagship for Task Force III.

ESCAPED PEARL HARBOR

For reasons shrouded in mystery, the USS Indianapolis was not in port at Pearl Harbor on the morning of December 7, 1941. In Edgar Harrell’s book, “Out of the Depths” — himself a survivor of the Indy ’s tragic sinking— he retells the account of Daniel Brady, a seaman second class aboard the Indy . According to Brady, the ship was docked across from battleship row and most of the men were ashore for liberty leaving about 1/3 of the crew aboard. On the morning of December 5th, the remaining crew was told to get the ship ready to leave in less than an hour, a nearly impossible task.

“Most of our crew,” Brady says, “Were ashore and we could never recall them in time on such short notice. Soon, 50 Marines in full battle gear came aboard…. Next came truckloads of food and vegetables, which were dumped unceremoniously on the bleached, white, teakwood quarterdeck!”

Within the hour the Indy was at sea having left behind most of her crew, and on her way to conduct drills some 700 miles southwest of Hawaii. She was spared the wrath of the Japanese assault on Pearl Harbor.

The Indy saw her first taste of combat in February 1942 in a small fight south of Rabal, New Britain, and again near New Guinea. By March of ’42, she returned to Mare Island, San Francisco for a refit to include search radar. Instead of sailing back to the South Pacific, the Indianapolis made her way north to help stop the Japanese invasion of the Aleutian Islands chain. She participated in the shelling of Attu and Kiska. The spring of ’43 found the Indy back at Mare Island for another overhaul to get her ready to become the flagship of Admiral Raymond A. Spruance and the Fifth Fleet.

As the flagship for the Fifth, the Indy participated in Operations Galvanic, Flintlock, and Forager lending fire support for Marines landing at Tarawa, the Marshall Islands, and Guam, Saipan, and Tinian respectively. She made it through the Battle of the Philippine Sea (known in Navy circles as the Marianas Turkey Shoot) without a scratch and was even credited with shooting down a Japanese torpedo plane. After the Marianas, the Indy set sail for Iwo Jima. According to Harrell, “The Indy’s mission was simple: Bombard [the Japanese]!” By March 1945, the Indy would find herself joining the pre-invasion bombardment of Okinawa. As fate would have it, the battles at Okinawa would set the Indianapolis on a path toward fame and infamy.

KAMIKAZE!

Early in the morning of March 31, 1945, while shelling Okinawa, a solitary Japanese kamikaze broke through the clouds and made its way for the Indy. Somehow making its way through a hail of anti-aircraft fragments, the plane crashed into the port side of the enormous ship causing little damage itself, but before it hit, the plane had released a bomb. According to Harrell, “the bomb tore through the deck armor, the mess hall, the berthing compartment below, and the fuel tanks in the lowest chambers before crashing through the bottom of the ship and exploding in the water underneath us.” Crippled, the Indy settled slightly at the stern and listed to port. Nine sailors were dead. But, the Indianapolis refused to go down. In fact, she sailed under her own power all the way back to San Francisco for repairs.

INDY AND THE MANHATTAN PROJECT

As fate would have it, the top-secret Manhattan Project in New Mexico was nearing completion and they needed a ship to transfer the fruits of their labor, the enriched uranium- 235 for the atomic bombs, to the South Pacific. The closest ship was the Indianapolis. On July 16, 1945, the Indianapolis left Mare Island on a record breaking crossing of the Pacific to Hawaii—2,405 miles in just seventy- four hours—with her secret payload. A six-hour turnaround in Pearl and the Indianapolis continued on to Tinian. In total, the Indianapolis sailed over 5,300 miles in 10 days with an average cruising speed of 29 knots.

After dropping off the atomic bomb components, the Indianapolis received orders to begin a three-day sail to Leyte Gulf to join the USS Idaho for gunnery practice and a new equipment shakedown before returning to Okinawa. Lacking sonar gear to detect enemy submarines, the Indy’s Captain, Charles V. McVay III, requested a destroyer escort, but this request was denied. The Indy Maru would go it alone. Also, Captain McVay was not told that the Japanese Tamon submarine group was patrolling their route and had already sunk the destroyer USS Underhill along the Indy’s course.

TORPEDOES ON THE STARBOARD SIDE!

Shortly after midnight on July 30 the USS Indianapolis was cruising at 17 knots in a moderate sea with poor visibility never knowing that lurking silently beneath the waters the Japanese submarine I-58, commanded by Lt. Cdr. Mochitsura Hashimoto, had detected what he believed to be a large battleship, possibly of the Idaho class. I-58 had the Indy lined up for the kill and Hashimoto calmly waited until he had the perfect shot. He didn’t want to miss. He launched six torpedoes. Three found their target.

Harrell recalls the moment the torpedoes struck. “The first torpedo pierced the Indy on the forward starboard side about forty feet in front of number 1 turret, where I slept. The concussion jarred me instantly to my feet. In the time it took Commander Hashimoto to say, ‘Fire one… fire two,’ the second torpedo hit around the midship, forward of the quarterdeck, somewhere in the close vicinity of my Marine compartment. Then, a few seconds later, a third explosion rocked the ship. It was the ammunition magazine underneath me. The explosion blew all the way through the top of turret number one.”

The explosions cut out all electrical power and communications across the ship. There was no way from the men in the helm to tell the engine room to shut down so the Indy, with nearly 35 feet of her bow completely gone, continued to plow into the seas at 17 knots. The result was that the protective bulkheads were buckling under the ocean’s weight, further driving the Indianapolis underwater.

“MY LAST VIEW OF THE INDIANAPOLIS WAS BOW DOWN, FLAG STILL FLYING ON THE STERN, AND MEN JUMPING INTO THE TURNING SCREWS. THEIR SCREAMS STILL HAUNT ME.”

Quickly, orders were given to abandon ship and of the 1,197 officers and men aboard, 880 were able to make it into the chilly, now oil-slicked waters of the South Pacific. Indy survivor John (Jack) C. Slankard recalled watching the last moments of the Indianapolis and her crew.

“My last view of the Indianapolis was bow down, flag still flying on the stern, and men jumping into the turning screws. Their screams still haunt me,” he said.

What followed were four days in the open ocean, surrounded by sharks, swimming in oil slicks, beneath the unrelenting sun. Of the nearly 880 men that made it into the sea, only 317 were pulled alive from the ocean four days later. Captain McVay did survive only to be faced with a Court Martial offense of “hazarding a ship” to which he was found guilty and ended a brilliant naval career.

On a crisp fall day in 1968, the Indianapolis would claim its last man when McVay took his own life outside his Litchfield, Conn. home. Thanks to the relentlessness of his crew, McVay was exonerated of any wrongdoing in 2000.

FOUR DAYS WITH THE SHARKS

A Conversation with Indy Survivor Edgar Harrell

“With no one left on the quarterdeck, I stepped over the rail and walked two long steps down the side of the ship that now made a ramp into the water. Then I jumped feet first into the murky, oil-laden ocean. As the ship went under, some boys who were still on board frantically ran up the fantail as it went vertical, but then it suddenly rolled to starboard. In their panic, several boys blindly jumped off, landing in the four big screws that were still turning, and quickly met their death.”

That’s how Edgar Harrell, a Marine aboard the USS Indianapolis, describes, in his book “Out of the Depths”, how he found his way into the South Pacific following the torpedoing of his ship.

ASG had the opportunity to sit down with Mr. Harrell and ask him about his thoughts on the sinking of the Indianapolis and how he was able to survive the horrible four days that followed swimming in shark-infested waters.

American Survival Guide: What did you do to survive the first day/night?

Edgar Harrell: I had my kapok [life] jacket on and I did as much swimming [as I could]. Plus, I helped those who were injured or without life vests. There was never a dull moment. I also helped my Marine buddy, Leland Hubbard, who was severely wounded and only lasted an hour or so.

ASG: After the first night, did you think you’d be in the water for another three days?

EH: No, we were to have met up with the USS Idaho the next day for gunnery practice. “While no one knew for sure, we tried to assure ourselves that an SOS got off the ship. Even if it hadn’t, surely the Navy would become alarmed when they discovered we failed to make our intended rendezvous the next day with the USS Idaho.”

Note: In fact, three SOS calls were made from the Indy before she went down. However, in the official inquiry that followed, the Navy claimed no such thing occurred. Also, the Navy had intercepted a message from the Japanese submarine I-58 reporting that it had sunk a ship in the vicinity of the Indy. The Navy ignored all these messages.

ASG: How much did you depend on others to get you through each day?

EH: I swam with my Marine buddy Miles Spooner tied onto me because he wanted to commit suicide. We also needed the warmth from each other in the 85- degree water at night.

ASG: Which was worse for you, night or day?

EH: The days were worse because of the 110-degree heat and the extreme thirst. The wind was up more in the days so the water was rough and more hazardous. Of course, the heat in the day caused extreme thirst and some men began drinking the seawater. “In the rough seas some boys accidentally swallowed some of the oil and had been vomiting all night and were now severely dehydrated and convulsing. They gradually became delusional and would thrash the water and shake violently until they finally lost control of themselves. Most of these never made it through the first day.” Plus, during the day, we could see the sharks and hear when they hit a shipmate. Nights are lonely, foreboding, cold and trying. You can’t rest for fear of wondering if you can make it through the night; there was some sense of hope during the day.

ASG: Can you talk a bit about the sharks?

EH: I certainly feared them. We could see the sharks and hear when they hit a shipmate. “Sadly, some of the hallucinating boys [most from drinking salt water] insisted on swimming away from the group to an island or a ship they were sure they saw. As they swam, their thrashing often attracted the sharks and we’d hear a bloodcurdling scream. Like a fishing bobber taken under the water, the helpless sailor quickly disappeared. Then his mangled body would resurface moments later with only a portion of his torso remaining.”

ASG: What did you do to help you survive?

EH: I never lost hope. I prayed and prayed. I prayed for God’s mercy, grace and endurance. I kept swimming and never gave up the will to live. ASG: Looking back, what are your thoughts about the Navy sending the Indy to Leyte and their subsequent treatment of the sinking? EH:We were sent out in harm’s way unescorted. The Navy knew the Japanese subs were working in those waters. Admiral King knew. The Navy did a fast cover up as to who was at fault. Most of the blame was on CINCPAC, and officials in Guam and the Philippine Frontier. The Navy sent the Indy on the mission and failed to protect us, failed to respond to our SOS’s. To the men, the Indy survivors felt betrayed by our own Navy. We fought the Navy for over 50 years demanding answers. I pray for the strength to continue telling the saga of the sinking of the Indy.

Editor’s Note: A version of this article first appeared in the August 2015 print issue of American Survival Guide.