In the early morning of August 21, 1910, Emma Pulaski, wife of one of America’s first forest rangers looked around the charred remains of Wallace, Idaho and the still smoking hillsides and was certain that her husband had died in the firestorm the night before. “The flames leaped all through the mountains until it seemed as though hell had opened up with all its horrors,” she would later write. “Mr. Pulaski was somewhere in those burning mountains and all though [sic] he knew every foot of the ground and could have saved himself, I knew he would not desert his men and would save them or die with them.”

MASSIVE FIRE

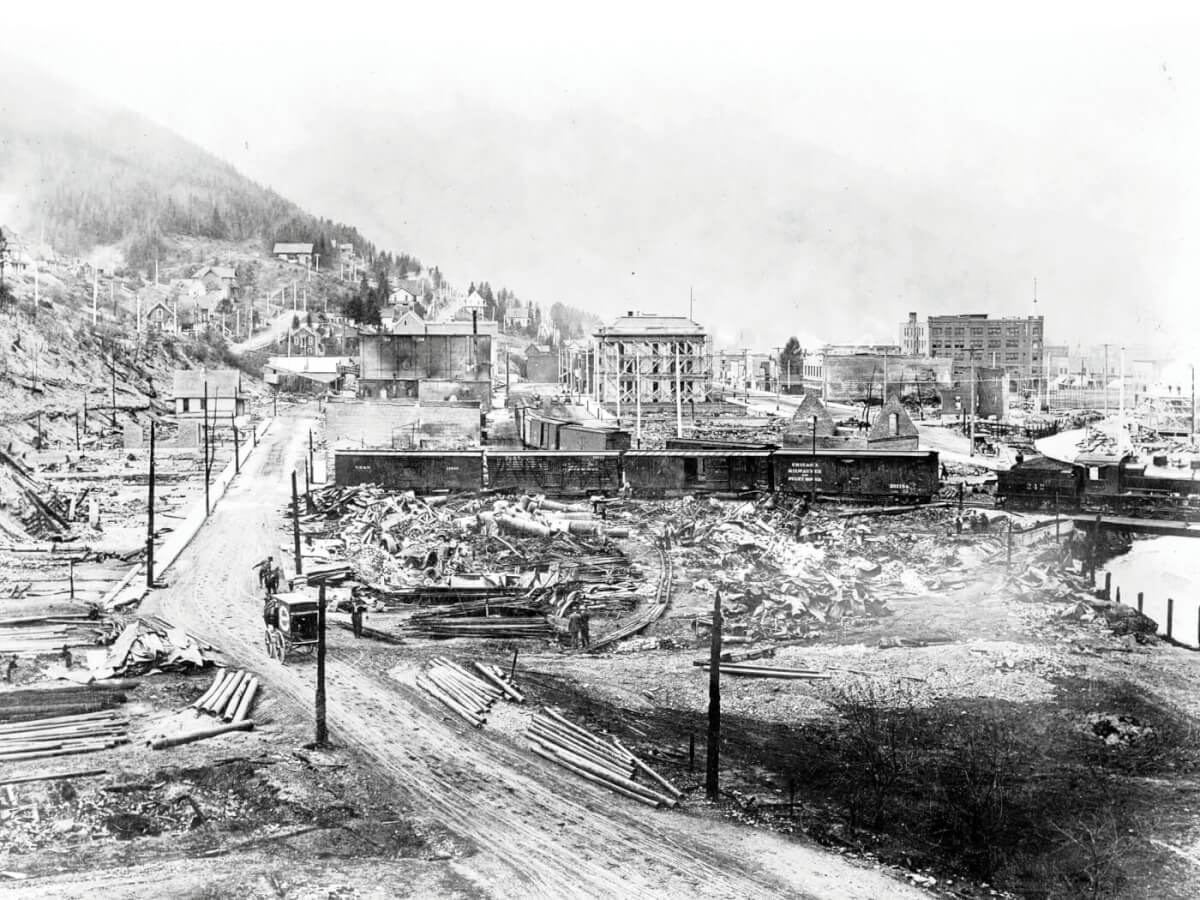

What had engulfed the tiny Idaho town of Wallace would later be called the Great Fire of 1910. It was a forest fire of staggering proportions. In two days, August 20-21, over three million acres burned in Idaho (panhandle), western Montana and eastern Washington; an area roughly the size of Connecticut. At least 85 people died—78 of those were firefighters. Seven towns were burned completely off the map. All of this puts the Great Fire, also called the Big Burn or Big Blowout of 1910, as the largest forest fire in U.S. history in size; though others would surpass it in death toll.

Even though the fire had decimated so much, not everything was lost, and, like the firefighters of the Forest Service crawling out of the smoky valleys, out of the embers stories of heroic survival emerged. One such story is that of Ed Pulaski whose wife recalls watching him limp down the road with the help of another man. He “was staggering,” she wrote in the 1930s in a short article called My Experience as a Forest Ranger’s Wife. “His clothes coated with dry mud, his eyes bandaged, he was blind and terribly burned, his hands and hair were burned and he was suffering from the fire gas.” How he survived is a testament to his devotion to his men and his will to live against all odds.

EMBERS SPARKED

The summer of 1910 had been a hot one. The winter snow melted early and the Pacific Northwest had not seen rain since May. In fact, 1910 was the third consecutive year of a drought that swept across the entire Northwest. Joe Halm, a Forest Ranger and Deputy Supervisor in the Coeur d’Alene National Forest at the time of the Great Fire, described those late August days as having “an ominous stifling pall of smoke” hanging over the valleys. Around him and the other rangers were anywhere from 1,000 to 3,000 small fires some started from sparks from passing trains, others from lightning, but all demanding the attention of the undermanned Forest Service.

“For weeks forest rangers with crews of men had been fighting in a vain endeavor to hold in check the numerous fires,” Halm would write in 1930. They worked in high mountain meadows that once abounded in fragrant wildflowers, but were replaced by the “tang of dead smoke.” The plants stood “crisp and brown, seared and withered by the long drought.”

Men labored side by side digging trenches with rudimentary tools hoping to encircle the fires and contain them. With blood red eyes and lungs that burned and begged for untainted air, they worked in an eerie pall of smoke where the sun rose and set in a dark red hue. “All nature seemed tense, unnatural, and ominous,” Halm wrote.

RISE OF A HERO

And it was into that unnatural world that Ed Pulaski set off on the morning of August 20th. He’d come into Wallace for more supplies for his crews in the woods surrounding Wallace, and spent a few hours with his wife and daughter. Soon, the mountains around them erupted into flame and the Forest Supervisor in Wallace, William Weigle, instructed Pulaski to return to the fire lines with more men and supplies. Pulaski looked at his wife and told her that he was certain that Wallace would burn. He wanted her to leave before then. Together they went to the edge of town and, according to Emma, Mr. Pulaski “said good bye I may never see you again he went up the mountain and we went home.”

Ed Pulaski had an adventurous spirit and that spirit would serve to save him and his men. Born in 1884 in a small town in Ohio, Ed was lured West by letters from an uncle working in the gold fields and boisterous mining camps. “Big Ed” as he was called—he stood a towering six foot four inches— roamed the West picking up blacksmithing skills while he worked as a packer, mine laborer, and in the lumber camps of Idaho. His supervisor, William Weigle, wrote that Ed “is a man of most excellent judgment; conservative, thoroughly acquainted with the region, having prospected through the region for over 25 years. He is considered by the old-timers as one of the best and safest men to be placed in charge of a crew of men in the hills.” Despite the respect afforded him, Ed Pulaski was an enigmatic and reserved man.

Pulaski was tasked with organizing the many crews fighting the various fires around Wallace. He went from camp to camp giving directions as to how to fight each fire. He was also responsible with making sure that the pack teams were making their way into mountains, into the heart of the flames, bringing vital equipment and supplies to the beleaguered men. As he went deeper into the forest he knew so well, the landscape changed into an unfamiliar, haunting world. “For weeks there had been no rain and the woods were drier than I had ever seen

them,” he would later say. Around him were “crews of several hundred men working 24 hours a day throughout the mountains, endeavoring to hold back the fires.”

NO ESCAPE

However, their efforts would be futile.

“Although we worked day and night and did everything that could be done to control the fires, little headway was made because of the dryness of the forest and those strong winds.” By the evening of the 20th, hurricane force winds swept across the mountains and swirled the many smaller fires into one massive, raging inferno. According to Pulaski, “the wind was so strong that it almost lifted men from the saddles of their horses, and the canyons seemed to act as chimneys, through which the wind and fires swept with the roar of a thousand freight trains.”

Nearby, Halm and his men were experiencing the same thing. “Meanwhile the wind had risen to hurricane velocity. Fire was now all around us, banners of incandescent flames licked the sky. The quiet of a few minutes before had become a horrible din.” Both supervisors were faced with a fire that was beyond control and men who were now becoming delirious with fear.

Pulaski knew that staying and fighting the fire was foolhardy at best. His only option was to rescue as many men as he could.

TO THE MINESHAFT

“I got on my horse and went were I could, gathering men.” Most of the men in his group were unfamiliar with the territory so he knew that it would be up to him to lead them out to safety. Eventually, Pulaski was able to gather forty-five men, his voice hoarse from yelling over the noise of the wind and fire, and directed them to follow him out of the “raging, whipping fire.”

He quickly decided that their best bet for survival was one of the many abandoned mine shafts that dotted the hillsides. Ordering the men to gather blankets that could be used to block the mine entrance, he daringly led the men though burning, falling trees and a smoky darkness that made it nearly impossible to see. They raced for the nearby mine. Pulaski notes that one man was killed on the way by a falling tree, but they “reached the mine just in time, for we were hardly in when the fire swept over our trail.”

Pulaski ordered his men to the ground to escape the smoke and fire gas. One man, desperate and crazed, tried to run out of the tunnel into certain death. Pulaski drew his revolver, told the men that no one would leave, and the first one that tried to get out he’d shoot. “I did not have to use my gun,” he said. The fires outside the tunnel were so intense that the mine timbers caught fire. Pulaski began to hang wet blankets over the opening, but those would eventually catch fire and he’d have to replace them. Behind him, the men were crying, praying and a few lost consciousness due to the heat, smoke, and gasses.

Eventually, Pulaski fell unconscious at the mine entrance. “I do not know how long I was in this condition, but it must have been for hours.” Regaining consciousness, he remembers hearing men standing around him saying, “Come outside boys, the boss is dead.”

He raised himself up, took a deep breath of fresh air, and said, “Like hell he is.”

Parched, the men went down to the creek for a drink, but found that it was filled with ashes and too hot to drink. Grateful to be alive, the men looked around the bleak, smoky landscape and did a quick head count. Five men were missing. They returned to the mine and found that they had died. The remaining men walked, and at times dragged themselves on hands and knees, over still burning logs and smoking debris toward Wallace. “We were in a terrible condition,” Pulaski said. “All of us hurt or burned. I was blind and my hands were burned from trying to keep the fire out of the mine. Our shoes were burned off our feet and our clothing was in parched rags.” Once in Wallace, and his men safely in the various hospitals, all Ed Pulaski could think about was his wife and daughter, especially after seeing that much of Wallace had burned. Only after hobbling down the road with the help of another ranger and seeing that Emma and his daughter Elsie were well did Ed Pulaski finally retire to a hospital bed.

THE SURVIVORS

Of the forty-five men that Ed Pulaski was able to round up, 39 survived thanks to his quick wits and his intimate knowledge of the area surrounding Wallace. Ed Pulaski spent two months in the hospital dealing with blindness and pneumonia. He would eventually regain sight in one eye, but he was left with weak lungs and scars that he would carry with him throughout his years in the forest service. He never received compensation from the U.S. government for his injuries. Worse still, the Forest Service refused $435 in funds for a memorial designed by Pulaski dedicated to the men who had died in the Great Fire, claiming that it would have taken “an act of Congress.”

He retired from the Forest Service in 1929, and he died two years later.

Though the fire devastated the towns of Wallace, Burke, Kellogg, Murray, and Osburn, towns like Falcon, Grand Forks, Henderson, and Taft were completely destroyed and never rebuilt. The big burn killed 87 people, burned thousands of acres, and is still considered the largest forest fire in the history of the United States. It not only helped to elevate firefighters as heroes, but the big burn brought to the forefront an enlightened concept of forest conservation as well as the government funds necessary to develop and maintain a properly-equipped National Forest Service in the United States.

Editor’s note: A version of this article first appeared in the Fall 2015 print issue of American Survival Guide.