It was an unusually cold, steady rain for late May, and the Conemaugh River began spilling its banks, leaving kneedeep water throughout the city of Johnstown, Pennsylvania. The people of Johnstown had been through this before; their city lay nestled on a high valley flood plain in the shadows of the Appalachian Mountains. They worked together to get merchandise from shops up to second floor storage rooms, household goods were stuffed into upstairs bedrooms, and animals were let loose from their bindings in barns across town.

No one flinched when the warnings came through the telegraph that the dam up stream may fail. They’d heard it before. There was a time, years ago, when people spoke of the possibility of the dam bursting, but the wealthiest people on earth were, after all, maintaining it.

Fourteen miles upriver from Johnstown stood one of the largest earthen dams in the world. Initially constructed by the Pennsylvania Mainline Canal, the South Fork Dam was purchased by the South Fork Hunting and Fishing Club from the Pennsylvania Railroad who had abandoned the dam shortly after the Civil War. Rebuilt by the club, it rose nearly 80 feet over the valley floor. Behind it sat Lake Conemaugh, a two mile long, one mile wide—at its widest—and 60 feet deep pleasure lake for Pennsylvania’s elite including Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, and Philander Knox.

No matter how hard the rains fell, the South Fork Dam had always held. A sense of complacency fell over Johnstown, despite what some called “the sword of Damocles hanging over Johnstown.” One of those who were concerned was Daniel J. Morrell, president of the nearby Cambria Iron Company and the most powerful man in the valley.

Morrell was concerned enough to become a member of the elite club and bring in his own engineer to inspect the dam. Though none of the original reconstruction was done with the advice of engineers, the discharge pipes at the base of the dam were removed, the spillway covered in netting to prevent the lake’s precious trout from escaping, and the top of the dam was actually lowered to accommodate two-way traffic, Morrell’s concerns were dismissed off hand by the club’s president, Benjamin Ruff. “You and your people are in no danger from our enterprise.” Morrell would die four years before the sword came crashing down on Johnstown. A long-time resident of Johnstown put it succinctly when he said, “People wondered, and asked why the dam was not strengthened, as it certainly had become weak; but nothing was done, and by and by they talked less and less about it, as nothing happened, though now and then some would shake their heads as if conscious the fearful day would come some time when their worst fears would be transcended by the horror of the actual occurrence.”

On the morning of May 31, 1889, above the tranquil valley in his cabin at the Fishing Club, newly elected club president, Elias Unger, woke to a sight he’d never imagined. The lake had risen two feet overnight. In fact, modern forecasts have estimated that the entire region had received nearly 10 inches of rain in 24 hours. So much rain had fallen that normally calm creeks raced like violent rivers.

Unger gathered the grounds crew and together they frantically tried to hold back Lake Conemaugh. The front of the dam had become a honeycomb of water and resembled a water can. Atop the dam, Unger and his men tried to clear the fish netting which now blocked the only spillway for the dam with trees and other refuse. There was even an attempt to cut a second spillway along the far edge of the dam, but this was ultimately abandoned. Twice, Unger sent his chief engineer down stream to the nearby town of South Fork to alert the telegraph office of the dire circumstances at the dam. At 1:30, Unger realized that their effort were futile and ordered his men to higher ground. All they could do now was watch. At 3:10, the dam gave way and within 40 minutes, 20 million tons of Lake Conemaugh had completely drained from behind the dam.

In Johnstown, 16-year-old Victor Heiser stood beside his father in their home on Washington Street. As they watched the water reach knee height, the elder Heiser became concerned for their two horses in the barn behind the house. He sent his son to work his way through the rising waters to untie the horses. A block away on Locust Street, Mrs. Anna Fenn sat in the family home surrounded by her seven children. She watched the water rise and worried about her husband, John, who’d gone to their tinware and stove shop to move merchandise to a safe place. As the waters rose around his store, John Fenn decided to rush home to be with his family. What neither of them realized was that the South Fork Dam had already failed and 20 million tons of water— the equivalent to the amount of water flowing over Niagara Falls in 36 minutes—was rushing toward them.

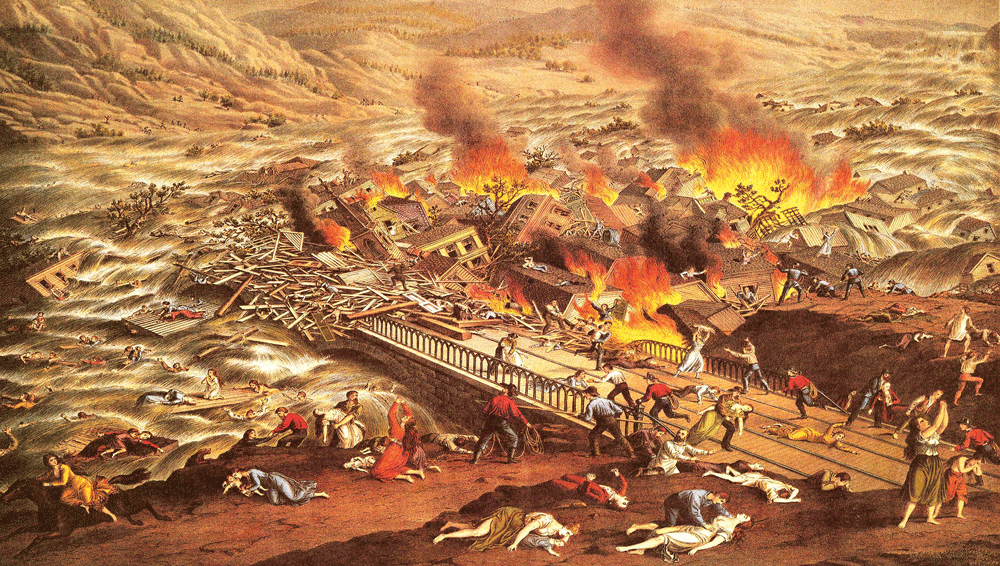

By the time the floodwaters reached Johnstown, it had ripped through four towns— leaving only bare stone where one once stood, the Gautier barbed wire factory where it gathered miles of wire, and the Cambria Iron Works. It had picked up dozens of locomotives and railcars, countless buildings, the bloated bodies of almost 400 people—314 from the town of Woodvale alone—and an untold number of animals. It was traveling close to 40 miles per hour and reached heights of 60 feet.

Victor Heiser had just released the horses and was turning to return to the house when he heard the crashing waves enter the city. From his memoir, An American Doctor’s Odyssey, Heiser noted, “The dreadful roar was punctuated with a succession of tremendous crashes. I stood for a moment, bewildered and hesitant.”

In the second-floor window of his boyhood home, he saw his parents frantically waving for him to climb to safety. Turning, Victor raced to the only safe place he could— the roof of the barn. Panicked he turned toward the wall of water churning toward him. “It was not recognizable as water, it was a dark mass in which seethed houses, freight cars, trees, and animals. As this wall struck Washington Street broadside, my boyhood home was crushed like an eggshell before my eyes, and I saw it disappear.” Victor Heiser’s parents would become two of the total 2,209 people killed in the Johnstown Flood. But for Victor, this was only the beginning of his perilous fight for survival.

“EVERYTHING WAS DARK, THE HOUSE WAS TOSSING IN THE WATERS, BUT SHE COULDN’T TELL THE EXACT MOMENT THAT HER CHILDREN GAVE UP THEIR GRASP AND SUCCUMBED TO THE WATERS.”

Within seconds, the tempest smashed against the barn. Victor clung to the roof shingles expecting the worst. However, instead of being smashed to pieces, the barn was lifted completely off its footings and tossed in the water. It began to roll and tumble in the water like a barrel, sending Victor scrambling to his feet. Stumbling, crawling, racing, he struggled to keep himself topside. Directly in his path was the Fenn house, and inside yet another horror unfolded.

We can only imagine the fears that John Fenn felt when he heard then saw the wave approach, but we do know that he never reached his home. Inside the home, Anna Fenn clung to her baby while the other six children grasped hopelessly at their mother’s dress. Anna would later recall that the water rose until their heads were touching the ceiling. Everything was dark, the house was tossing in the waters, but she couldn’t tell the exact moment that her children gave up their grasp and succumbed to the waters.

Outside, Victor continued to tumble across the rolling barn as it sped toward the Fenn house. Just as the barn was about to smash into the home, Victor leapt “into the air at the precise moment of impact. But just as I miraculously landed on the roof of her house, its wall began to cave in….” Victor clung helplessly to the eaves of the shattered roof while Anna Fenn was swept into the roiling waters. As his hands finally lost their strength, Victor fell into the abyss below him. Fortunately, Victor landed atop the familiar barn and once again, he was rafting wildly through the demolished remains of Johnstown. “Lying on my belly, I bumped along on the surface of the flood, which was crushing, crumbling, and splintering everything before it. The screams of the injured were hardly to be distinguished above the awful clamor; people were being killed all about me.”

Everyone reacts differently to crises and the stresses that they bring about. Victor did everything he could to survive. Jumping from building to building and doing what he could to stave off certain death. Not everyone reacts this way. Some freeze like those who stood dumbfounded as they watched the wall of debris and water sweep them off their feet. Others, like the Musantte family, went into a hysterics. As Victor dealt with the danger of managing his plank of a ship through waters tangled with barbed wire, rafter beams and trees being pushed up and sunk back into the water he watched as the Musantte family frantically tried to pack their Saratoga trunk with all their household possessions. Moments later, the barn floor they were adrift upon was smashed and the entire family drowned.

Eventually, Victor found himself on the roof of a two-story brick building that had withstood the raging flood. He huddled there with nineteen other people. He watched Anna Fenn drift by clinging to a tar bucket that had spilled its contents all over her. A mere ten minutes had elapsed from the time the family barn was hit by the wave until he found his final refuge. In the distance, the stone bridge of the Pennsylvania Railroad had acted as a dam, capturing all the debris and bodies. Sometime that night, the debris caught fire. Years later, Victor would reminisce: “I can still hear the maddened shrieks of the men, women and children, as the flames approached. I joined the rescue squads and we struggled for hours trying to release them from this funeral pyre, but our efforts were tragically hampered by the lack of axes and other tools. We could not save them all. It was horrible to watch helplessly while people, many of whom I actually knew, were being devoured in the holocaust.”

Victor Heiser would leave Johnstown, work a few odd jobs, and then enroll in medical school. As a medical doctor in the Navy, he travelled the world for three decades working to prevent disease, rather than just cure it. That Victor Heiser survived his ordeal is nothing short of a miracle. His fight for survival was an intensely personal one, almost selfish in that he was fighting for himself while others died around him. What he could never have known, as he clung to the side of the Fenn house or ran across the rolling barn, was that his fight for survival ended up saving so many more lives. For, sometimes all it takes are the selfish, instinctual survival behaviors of one person to have a selfless impact on the lives of millions.

Editors Note: A version of this article first appeared in the January 2015 print issue of American Survival Guide.