As children, we often find ourselves playing the classic game of hide and seek; hunkering in the neighbor’s hedges or up some tree hoping we can elude our friends the longest. As we dare to peek from our hideout, just to see how close the seeker might be, a surge of adrenaline makes our muscles tense. A wave of excitement rushes over us as we watch them walk not a few feet in front of the hedge or below the tree, forcing us to stifle a giggle or be found. And, if we were found, the greatest consequence we’d face was becoming ‘it’.

No one ever imagines the game of hide and seek could be a matter of survival. But, for Scott O’Grady, that’s exactly what it became when he was shot down during the Bosnian War in 1995 as a part of the NATO forces enforcing the United Nations (UN) no-fly zone over Bosnia as a part of Operation Deny Flight.

The story of Scott O’Grady’s six days in Bosnia is told in two books: Return With Honor (by Capt. Scott O’Grady with Jeff Coplon) and a young adult work Basher Five- Two (by Scott O’Grady with Michael French). In them, O’Grady starts out in a briefing where he and his flight lead, Captain Bob “Wilbur” Wright, review the search and rescue (SAR) plans should anything go wrong on their sortie over Bosnia.

In Return With Honor, O’Grady remarks of the discussion that, “While I’d glanced at our written SAR material some weeks before, it wasn’t something I’d spent much time studying. In the real world, pilots can’t map out escape and evasion ploys in advance. There are too many variables outside your control, from terrain and injuries to the proximity of hostile forces.”

Ultimately, O’Grady’s SAR was improvise, react to circumstance, and rely on common sense. Survival scenarios were not a top priority that day, not out of nonchalance, but no one ever expects to become a victim. For O’Grady, he had a job to do: To patrol the air space over Bosnia and prevent any of the combatants in the war from utilizing the air to gain a military advantage.

“MY FIRST THOUGHT WAS ANGRY AND SIMPLE: WE’VE BEEN SET UP. THEY LAID A TRAP FOR US, AND ALL OF OUR DETECTION SYSTEMS HAD MISSED IT. I WAS SWIMMING STRAIGHT INTO THE JAWS OF A SHARK.”

Three hours after the briefing, suiting up, and prepping the aircraft, O’Grady and Wright were on their way from Aviano Air Base in Italy toward the Bosnian coast. Their patrol would take them on a 25 mile long racetrack-like oval over Bosnia where they’d watch for any aircraft attempting to violate the UN no-fly rules. Their first circuit over Bosnia and refueling high above the pristine Adriatic was an uneventful run, but little did they know that, below them, Bosnian Serb forces had secretly moved an SA-6 battery south.

As O’Grady and Wright set up for a second CAP (combat air patrol), Wright’s threat warning system warned he was “spiked” or that an enemy radar system was watching him from the ground. Though it didn’t mean they were actually firing missiles, O’Grady says, “they sure might be thinking about it.” It was quickly determined to be a false alarm, but it got both pilots’ attention.

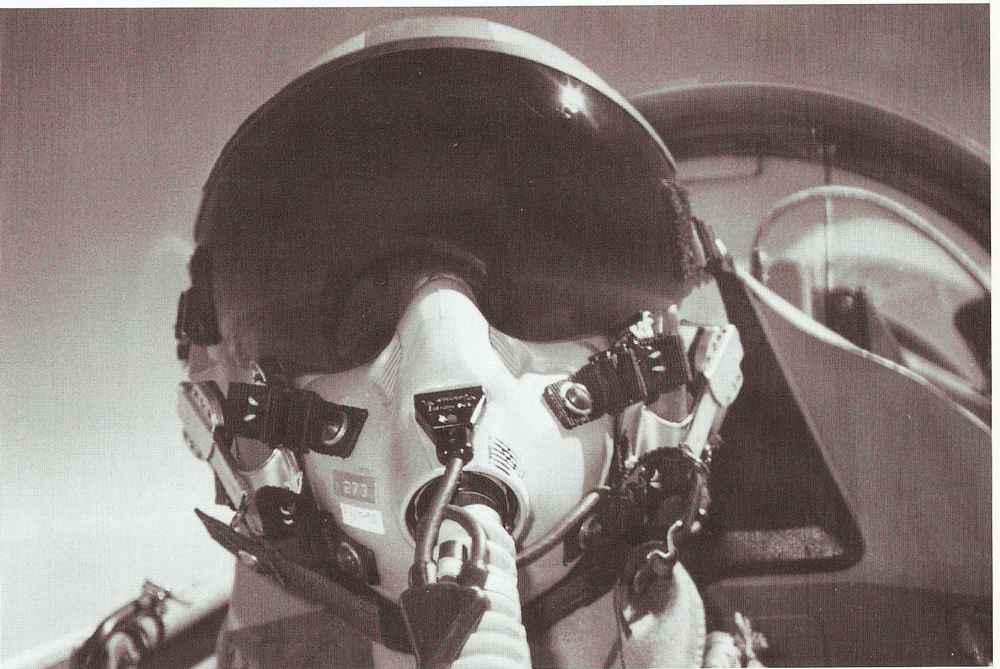

At 3:03 p.m. in the afternoon of June 2, shortly after the first spike, O’Grady’s radar warning system began to chirp. He was spiked. “You might say I felt uneasy. I didn’t like being stared at, especially when the staring might preface a ballistic payload, aimed straight at my gut.”

Seven seconds after the spike: O’Grady was pushing his F-16 to its flight limits in an effort to evade and survive. “My first thought was angry and simple: We’ve been set up. They laid a trap for us, and all of our detection systems had missed it. I was swimming straight into the jaws of a shark.”

Eight seconds after the spike: a programmed female voice in O’Grady’s headset called out, “Counter, Counter.” He went to deploy the chaff flare system.

Nine seconds after the spike: A searing red flash of a missile exploding between Wright’s and O’Grady’s jets lit up their cockpits. Ten seconds after the spike: They weren’t safe. SA-6s come in sets of three. There were two more missiles streaking toward them at supersonic speeds. Wilbur yelled: “Missiles in the air!” but O’Grady never heard it. “Within a second after that red flash, all I could hear was the murderous bang that swallowed me whole, like the whale that got Jonah…. When a plane and a missile collide, the plane finishes second.”

In the next fraction of a second, strapped into an F-16 that was now severed in two and quickly becoming a flaming torch engulfing him in blistering heat while disintegrating around him, O’Grady took a moment to say a quick prayer asking God to save his life and then reached down between his legs and pulled on the yellow handle of the ejection seat.

Hanging beneath a candy-colored, 28 foot canopy and “as conspicuous as the Goodyear blimp” he took inventory: hanging at the bottom of a 25 foot nylon cord was his vinyl rucksack that contained most of his survival gear; half-way up the line was a partially inflated raft. Closest to him, near his seat kit, was an auxiliary hit-and-run kit. He checked his body and found that the burns he suffered in the initial strike had eased into a chronic but bearable smarting. Then he scanned beneath him for a suitable landing place. What he found was that he was drifting over a highway with a truck that resembled a “military truck with a canvas top in back, the type seen on Hogan’s Heroes. The type they crammed with soldiers.” The truck, and another car, had stopped along the shoulder and O’Grady couldn’t help but wonder if he was a mere curiosity, a target, or a hostage-to-be as he dangled beneath his parachute.

“HE REMEMBERED WHAT HIS SURVIVAL INSTRUCTOR HAD TOLD HIM ABOUT EVASION: “JUST DON’T MOVE. DON’T ASSUME THEY SEE YOU JUST BECAUSE YOU SEE THEM.”

Once on the ground, with the truck and car not more than a mile up the highway, O’Grady rushed to release himself from the parachute gear and gathered his survival equipment which was now tangled in the chute lines. Seconds were ticking away. Seconds the men who were on their way to find him were using to close in. Seconds he couldn’t afford to waste untangling the nylon cord holding his rucksack. “Maybe that’s why I made my mistake — or maybe I just had too much to deal with in a flash of time. The fact remains that I left behind my hit-and-run auxiliary survival kit within its canvas shell, with my backup radio and half my ration of water inside. I simply forgot it in my haste to get away.”

Having left his parachute behind, O’Grady sprinted into the woods with his rucksack tucked beneath his arm as though he was playing running back for Notre Dame. Counting on adrenaline, he hoped his “fight-or-flight juice would carry me forever, but after 30 seconds I was sucking air.” The entire weight of the afternoon’s events came crashing down on his body and he couldn’t go any further.

Knowing he’d have visitors sooner than later, O’Grady dove into a stand of aspen-like trees and burrowed himself behind a small tree root. Nearby, he could hear vehicles and voices near the spot he left his parachute, the last of the vehicles grinding to a distinct truck-like stop. With one last moment alone, he tried to reach Wright somewhere above him, not knowing if Wright had even seen his chute deploy. He got out two quick transmissions before “the grass rustled with footsteps, coming my way. Coming with the careless noise of men who know their prey is cornered.”

Within moments, two men, one white-haired and the other younger, possibly a grandson, approached not five feet from where O’Grady lay, curled into a fetal position, his green synthetic flight gloves covering his face and ears. He held his breath and prayed that he could disappear into the black Bosnian soil. He remembered what his survival instructor had told him about evasion: “Just don’t move. Don’t assume they see you just because you see them.” Hide and seek on a life or death scale. But the men kept walking without a hiccup in stride or conversation.

But this victory, a blessing from God as O’Grady puts it, was short lived. Now, groups of two and three men were scouring the underbrush. Over the next hour, O’Grady watched as 15 or so of them, this time armed with rifles, dressed in civilian clothes, wandered around his hole-up.

For the next six hours, he spent his time in prayer and frozen still by random gunfire in the distance. He thought about his parents, about his brother and sister, and about his own funeral. But he knew he couldn’t dwell on these things. The reality was he was there, it was all too real, and his “next mistake might be [his] last.”

Though there were risks in leaving his hole-up, around midnight O’Grady decided being close to the highway was worse than moving. He took inventory of the things he had: The torn bags holding his survival gear could be discarded (useless and noisy), his harness with its metal clips could go (too visible and noisy). The rest he’d carry. It was not time to sort out the remainder of the survival gear.

The next challenge: Getting up off the ground. “Anyone blessed with a healthy body does this every day, without thinking, but it’s a whole different enterprise when you must do it without sound.” After what felt like an eternity of move, pause, listen, repeat, O’Grady grabbed his rucksack and began the slow crawl away from his hideout. It took him a solid hour to get out of that place.

Moving only at night, O’Grady utilized the BLISS principle he’d been taught to secure a place to hide through the day: “a hole-up should Blend into its surroundings; be Low and regular In Shape; set in a Secluded area. My wish list also included a decent angle for observation, an avenue for escape, a good spot for radio reception, and protection from the elements.” After another visit from the old man and the grandson at his second hole-up, O’Grady decided he was still too close to the road. He moved deeper into the forest and found the second of five hole-ups. However, each morning he realized the dark night had played tricks on his eyes; the hole-ups he created weren’t as hidden as he’d thought, and he had to make early morning adjustments or move a quick second time. Two of the days, while lying in his hole-up, he was visited by a herd of cows — two in particular he named Leroy and Alfred — and their tender who insisted on ringing a bell constantly and earned the nickname Tinkerbell.

“IF HELP DIDN’T COME? I WAS GOING TO SURVIVE.”

With food in little supply, O’Grady ended up dining on red ants, grass and leaves that he tested as safe by eating one, waiting an hour to see what it might do, and then eating a few more. With no ill-effects, he plucked the cleanest ones he could find and ate them. By the fourth night, his meager water supply was exhausted. O’Grady followed the SERE rule: “Ration sweat, not water” and made sure the best place to store water was in his stomach. As an answer to his prayers, something he believes brought him through those six nights, the skies opened up and poured. Using a small yellow sponge, he wiped his rucksack and any other place where water, no matter how small a pool, gathered. And every time he had a chance, he would briefly check in on the two emergency frequencies to see if anyone was out there looking for him.

After six long, tiring, and frightening nights behind enemy lines in Bosnia, and after one missed opportunity at making contact with a search plane, O’Grady’s ritual of beacon, pray, monitor, sit, wait — what he calls the “Bosnian cha-cha” — finally transmitted three distinct clicks on his radio. At 2:06 a.m. he heard: “Basher Five-Two (his call sign), this is Basher One-One on Alpha.” Salvation was close at hand. Five hours later, men from the 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit (TRAP force), aboard their CH-53Es covered by two Marine AH-1W Super Cobras, landed and extracted an exhausted, but grateful, Scott O’Grady from Bosnia.

It wasn’t until he was aboard the USS Kearsarge, in the medical ward, O’Grady admits he finally stopped trying to survive. In an interview days later, a reporter asked, “Did you have a contingency plan if you weren’t picked up? What were you going to do if help didn’t come?” O’Grady’s response was simple and perfect: “If help didn’t come? I was going to survive.”

Editors Note: A version of this article first appeared in the May 2015 print issue of American Survival Guide.