The saloon was eerily still. All eyes were on the six-foot-tall shell of a man who stared off into the musky din with steely blue eyes. The question lingered in the air like the pipe smoke swirling from the mouths of the men standing around him: Did you really eat people?

Finally, after moments of painful silence, Lewis Keseberg turned, flashed a smile that chilled the bones of the men in the room, and said, “Human liver is the sweetest thing I’ve ever eaten.”

Lewis Keseberg was the last person retrieved from the snowbound hell that befell the Donner Party in 1846-‘47. Though he wasn’t the only member of the ill-fated group to resort to cannibalism, despite claims that it never happened, he was the only one tried for murder. While Keseberg wears the anointed crown of evil personified in the Donner Party tragedy, he lays out reasons why the balance of justice might just sway back in his favor: “I have been born under an evil star! Fate, misfortune, bad luck, compelled me to remain at Donner Lake. If God would decree that I should again pass through such an ordeal, I could not do otherwise than I did.”

The story of the Donner Party is one of sheer survival and the determination of man to live. But it is also the story of how to survive and how to prevent yourself from ever having to face the darkest moments in life. Keseberg’s fate was cast the day he joined with the Reed family and the Donner brothers on their journey to California.

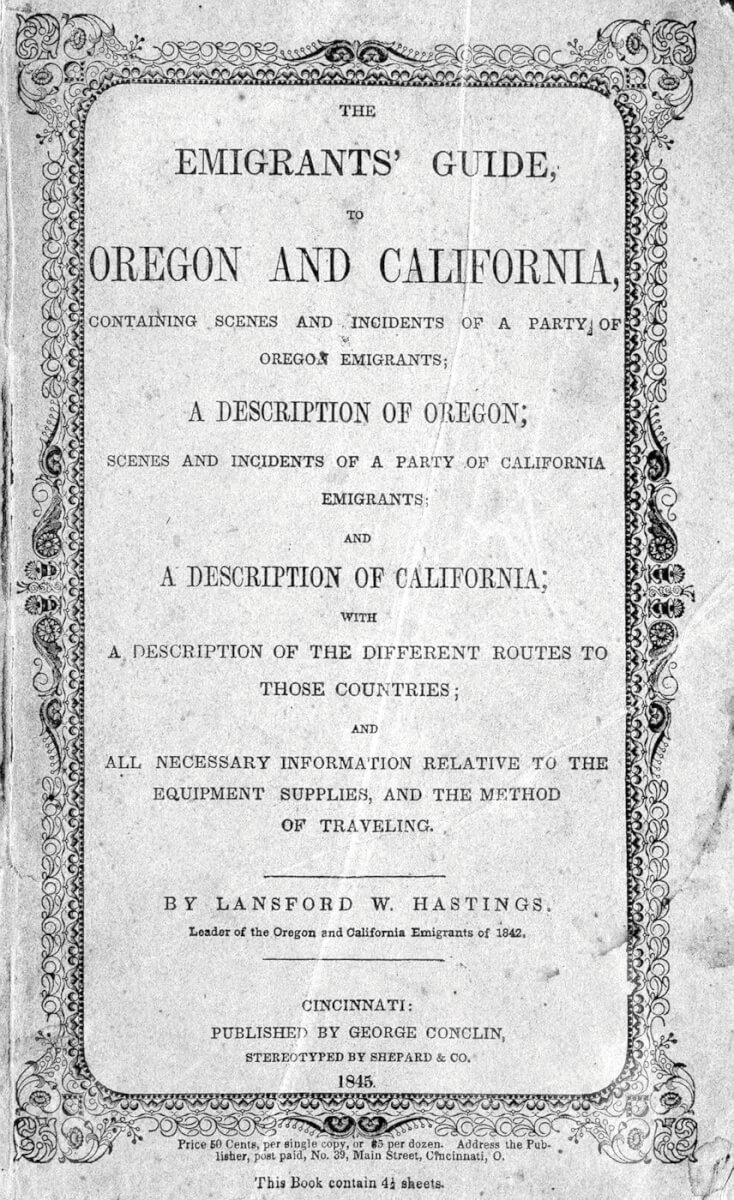

Travelling out of Springfield, Illinois with the Reed family were the brothers George and Jacob Donner and their kin. All three families had packed their wagons according to a guidebook published by Lansford Hastings, a man who’d never made the trip himself. Necessities included: One wagon loaded with bolts of cotton and flannel, glass, beads, mirrors, and other trinkets to trade with the Indians; expensive items like textiles, silks and satins to trade with the Californios upon arrival; farm equipment, furniture, and household goods. A second wagon was loaded with items needed for the trail. A third wagon was set aside as a shelter and dining cart.

It is surprising that George Donner or James Reed would have bothered with the suggestions put forth in the Hastings guide. Donner was well accustomed to moving. As the frontier pushed west, he had travelled with it from North Carolina with his parents, then on his own from Kentucky to Indiana to Illinois. He also spent time in Texas and had a familiarity working with oxen teams. He would have understood the most basic tenant of backwoods travel: Take what is necessary; leave the rest behind.

Reed served in the Black Hawk War and worked at one time or another as a merchant, railroad contractor, and furniture maker. People spoke of him as a man who was “quick with decisions and decisive in action.” Unfortunately for those travelling with Reed, he was also a self-made man and not one to play things safe. He didn’t come from a fatherless home to be one of Illinois’ more successful men by avoiding risks.

They’d left late from Springfield and had taken longer—due to their overburdened carts—than expected to reach Independence, Missouri. Though nothing in their journals indicates alarm, their arrival in mid-May was already weeks behind the accepted departure date for cross-continent travel. A late group was waiting in Kansas for any stragglers, and the Donner/Reed group wisely decided to leave quickly to catch up. This would be the last good decision that the Donner Party made.

Life on the trail was full of hardships. Swollen rivers, floods, disease and boredom. Routine became the most common way to cope with these. Women did the cooking and cleaning. Men tended the animals, hunted and repaired the wagons—mostly broken axles. Children, too, found chores to pass their time. They’d fetch the water, clean dishes and find firewood. The mundane helped alleviate the fears of the unknown.

Not all of the unknown hardships turned out bad. “The first Indians we met were the Caws,” wrote Virginia Reed in her diary, “Who kept the ferry, and had to take us over the Caw River. I watched them closely, hardly daring to draw my breath, and feeling sure they would sink the boat in the middle of the stream, and was very thankful when I found they were not like grandma’s Indians.” Aside from stealing horses, the Indians were a mild nuisance (most travelers on the Oregon Trail who were killed by Indians were done so west of the Parting Of Ways).

At Fort Laramie, he happened to come across James Clyman, an acquaintance from his Black Hawk War days. They spoke about the best trail west. Clyman was working his way east and had just come across the infamous Hastings Cutoff. He warned Reed against taking the trail, calling it impassable and said it was the most “desolate country perhaps on the whole globe.” He looked at Reed and implored that Reed “take the regular wagon track, and never leave it.”

Reed wanted nothing to do with what he considered a roundabout course if he could take a straight route to California and beat as many emigrants as possible. For Reed, he had one goal: Get to California and get land. To do that he was going to go straight. He placed his trust in Lansford Hastings who was, himself, leading his first group across the shortcut named for him just to try to prove its worth.

When the group reached Fort Bridger they had hoped to meet up with Hastings. However, he’d already left to lead a group across his trail. Having trusted their fate to what was becoming a remarkably unreliable man, it would have made sense for the Donner group to abandon their shortcut and swing north to catch the official trail to California.

Before them lay a blank world. Unlike the trails they’d traveled, this new cutoff had never been crossed and lacked the normal markings of the overland trails: Used campsites, river crossings, and, most importantly, wagon ruts to follow.

But Reed and Donner pressed on even against the wishes of George Donner’s wife. The men were quickly initiated into the hard life of mountain men. Their travel slowed to a crawl, as they tried to scout and blaze a trail across the Wasatch Mountains. They were forced to cut roads into the mountain, clear dense brush, and pull their exhausted oxen over the summit. What should have taken a week turned into nearly a month. They still had nearly 80 miles of alkali flats to trek.

It was here that the Donner Party was beginning to fracture. It became an every-man-for-themselves situation, where families, trying to avoid dehydration, would unhitch their animals, rush them ahead to any source of fresh water, return to haul their wagons a few miles, and then repeat. It was a disorganized panic. Animals were lost, wagons abandoned and tempers began to simmer. The fateful decision to use the shortcut had cost them two months before they reached the regular trail into California, near Elko, Nevada.

Instead of rallying behind a strong leader, the party plummeted into a death spiral of animosity and divisiveness long before they reached Truckee Lake on November 1, 1846. James Reed and John Snyder got into a heated argument over tangled cattle and when all was said and done, Snyder was dead and Reed banished from the party. Keseberg abandoned an old man named Hardcoop who was having trouble keeping up, and the rest of the party refused to help the man. Two members of the team murdered a third while helping him cache his supplies—an apparent attempt to steal his supplies.

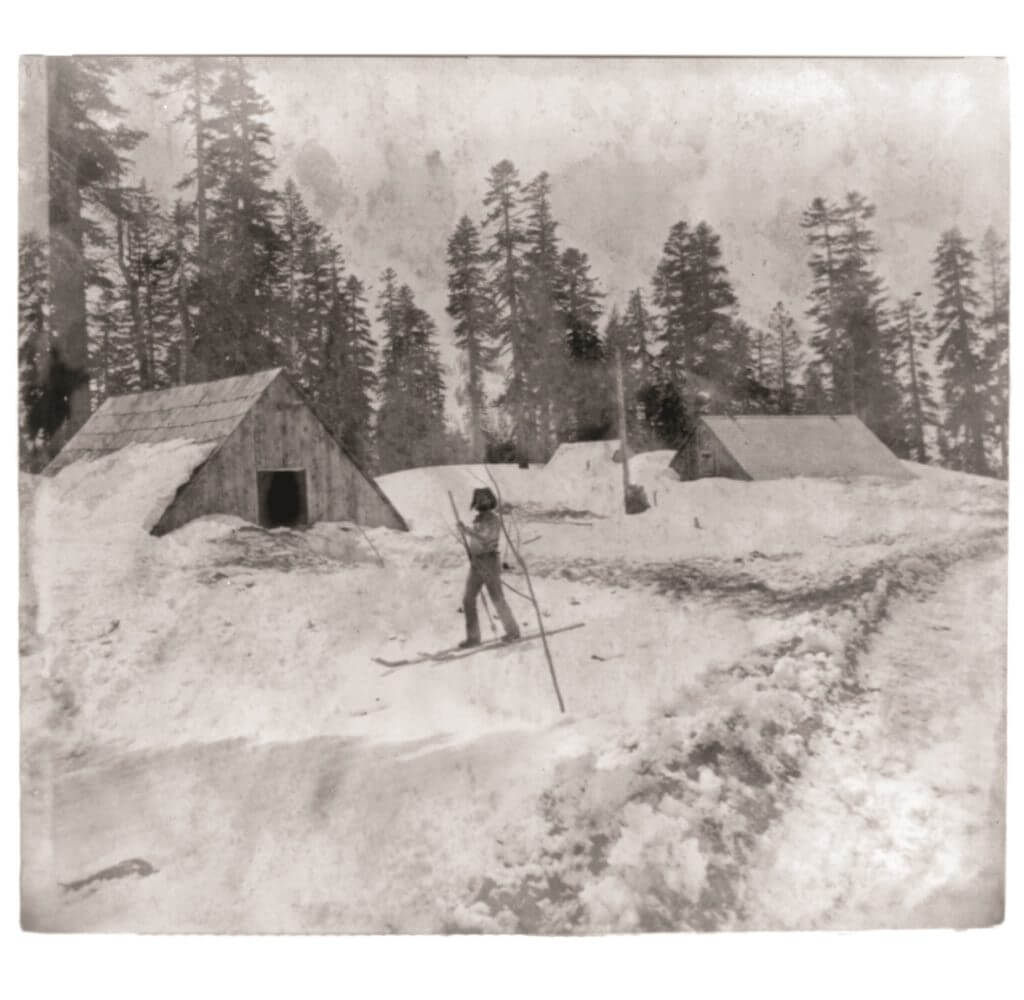

On October 12, the Piute Indians attacked and killed 21 oxen. Then it snowed… and it didn’t stop. They were stranded, and it all appeared hopeless. By Truckee Lake, they discovered three dilapidated cabins and settled in to wait out the storm.

Once in their snowbound prison, the Donner Party collapsed into a desperate greed of survival. Contrary to most group survival instincts where a shared calamity draws people together to survive, the members of the Donner party split apart and eventually established a string of camps of tents made from hides and ramshackle cabins nearly eight miles long from Truckee Lake (now Donner Lake) through Alder Creek. Families horded their scarce supplies and quickly exhausted their food supply. The pack animals were the first to be sacrificed for survival followed by the dogs and finally they resorted to boiling blankets and hides to make a paste-like soup. Families refused to share supplies with others in dire need or sometimes demanded ridiculous payments.

Faced with certain death, 15 members of the Donner Party formed what Virginia Reed called the “Forlorn Hope” and on homemade snowshoes set out for Sutter’s Fort in Sacramento. Four of the men left behind their families and three of the women left behind their children. In blinding snow, freezing nights, with no sense of direction, and no food, the group broached the idea of cannibalism. There was talk of having two people duel and the loser would become dinner for the rest. Ultimately, they decided to let the hand of death dictate who would feed the rest. The first to go was a bachelor named Antoine; while asleep, his arm fell in a fire and no one in the group woke him. In all, seven members of Forlorn Hope were eaten; two Indians that had come up from Sutter’s Fort to aid the Donner Party were hunted down and killed. Only seven members of the Forlorn Hope group reached Sacramento.

On February 19th, the first rescue party arrived. It would take four such groups and two and a half months before everyone was rescued. When the second relief group, led by Reed, reached Alder Creek, evidence of cannibalism was everywhere in what would become known as the “Starved Camp.” Imagine the difficult decisions that faced mothers as they looked at their starving children. It is most likely that many of the children ate the dead, but had no idea what it was that they were eating.

When the last relief group arrived at Alder Creek, they found Keseberg as the sole survivor wallowing in indescribable filth and the desecrated corpses of at least five people. George Donner’s head had been cleaved in order to retrieve his brain. Two kettles were filled with blood, livers and lungs.

Faced with unimaginable hardships the Donner Party resorted to the only thing they could in order to survive. Keseberg summarizes it best when he said, “A man, before he judges me, should be placed in a similar situation; but if he were, it is a thousand to one he would perish.”

Looking at those who survived and those who didn’t, a pattern emerges: Those families who stuck together— often through selfish means—survived, while the bachelors—like Hardkoop and Antoine—were quickly discarded or dispatched.

Certain social expectations, like kinship and family ties, will bind groups together no matter the circumstance. The Donner Party, from their trials in the Wasatch, to the drive across the Great Salt Lake, to their harrowing experience in the Sierras show that in dire times people will cope with hardships from our most basic nature: survive.

Editor’s note: A version of this article first appeared in the December 2014 print issue of American Survival Guide.