It is more convenient than ever to send and receive messages easily and quickly to and from anywhere in the world because of today’s cell phones, GPS equipment, and satellites, not to mention, email, social media and other assorted high-tech communication systems.

Throughout the most recent handful of centuries, there have been a host of outmoded communication techniques, but the usefulness and availability of Morse code has remained relatively steady. Though it is fading from the list of requirements of government programs (as of 2006, the FCC no longer requires ham radio operators to learn it), most military branches still offer a training course. One such course is at Ft. Huachuca in Arizona – a 72-day course where the course director, Major Scott Morrison, likes to say: “We use a Civil War invention, combined with World War I transmission technology, primarily targeted against Cold War adversaries, in support of today’s decision making needs.”

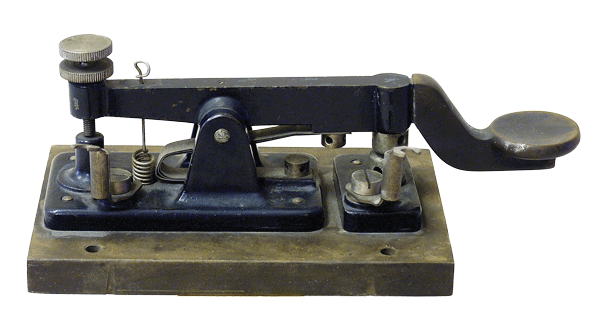

Morse code is the world’s first binary system, a simple on-off switch that can control a light, electric pulse, a tone, or a tap. It is used to transmit words and phrases in code electronically over great distances to be decoded on the receiving end.

HISTORY IN DOTS AND DASHES

Like most things, the electrical telegraph system wasn’t invented in a single day. While artist Samuel F. B. Morse was painting a portrait of Marquis de Lafayette in 1825, a messenger delivered a letter that said his wife was ill, followed by a letter the next day that said his wife had died. He didn’t even know she was sick, and by the time he had returned to his home in New Haven, CT, she had already been buried. Right then and there, he was inspired to find a way to quickly communicate over long distances.

Morse began studying electricity and electromagnetism. He met with countless scientists and researched many different options. Though Morse gets the namesake, he was helped greatly by physicists Joseph Henry and Alfred Vail.

In 1836, they created a system of electric pulses along wires that controlled an electromagnet at the receiving end; those pulses could be translated into words and phrases. Other inventors tried their hand at coming up with systems that would transmit messages over distances; some involved wheels pointing to letters while others printed them out. These other systems didn’t sell well, so they fell from use.

Morse’s system made indentations on the paper when the electric currents were received. Then the operator would translate these indentations into numbers which would then be translated into words. It was Vail’s idea to skip the middle decoding and expand the system to include the whole alphabet, and it was his idea to use a system of dots and dashes (the shorter sequences were given to the letters used more frequently).

In 1843, the United States Congress appropriated $10,000 to Samuel Morse in order to build an experimental telegraph line from Washington, D.C. to Baltimore, MD. Completed in late May 1844, it was demonstrated before Congress on May 24, with the world’s first Morse coded message: “What hath God wrought.” It was successful, and soon telegraph systems were being strung all along the eastern seaboard.

Soon, telegraph operators were so adept at translating the clicking of the machine’s armature, that they no longer needed the machine to make marks on the paper. Instead, they could translate the clicks directly into words by sound alone. They figured out that new operators could learn the code if it was taught as a heard-only language instead of read as a series of dots and dashes on a page.

By the 1890s, Morse code was being used for all communications over radio waves before it was possible to transmit voice. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, most high-speed international communication used Morse code on telegraph lines, undersea cables and radio circuits. In aviation, the U.S. Navy was first to transmit Morse code from an airplane; and during World War I, Morse code was used to coordinate bombing runs and navigation.

Beginning in the 1930s, both civilian and military pilots were required to be able to use Morse code, both for use with early communications systems and identification of navigational beacons which transmitted continuous two- or three-letter identifiers in Morse code. Aeronautical charts showed the identifier of each navigational aid next to its location on the map. During World War II very few battles, ships, or armies went into action without the benefit of Morse code.

Morse code was used as the standard for maritime distress calls (S.O.S) until it was replaced by the Global Maritime Distress Safety System in 1999. The French Navy was the last military entity that used Morse code, which was until January 31, 1997, when the final message transmitted was, “Calling all. This is our last cry before our eternal silence.” In the United States the final commercial Morse code transmission was on July 12, 1999, signing off with Samuel Morse’s original 1844 message, “What hath God wrought.”

HOW MORSE CODE WORKS

To understand how Morse code works, it is helpful to look at the method in which code is generated. To reflect the sounds of Morse code receivers, the operators began to vocalize a dot as “dit,” and a dash as “dah.” Dots which are not the final element of a character became vocalized as “di.” For example, the letter C was then vocalized as “dah-di-dah-dit,” but for the purposes of this article we will use, with a couple exceptions, “dot” and “dash.”

Code dots and dashes and the spaces between them are sent using a standard fixed time interval. A dot takes one unit of time, a dash takes three units of time, the space between the dots and dashes of the same character takes one unit of time, while the space between characters takes three units of time, and the space between words takes seven units of time. When sending code at a given speed, these units of time remain fixed in duration, and consequently the letters and words take varying amounts of time to send. For example, an E (dot) takes one unit of time to send while a Y (dash-dot-dash-dash) takes 13 units of time to send. Similarly, words, even those having the standard number of characters (five), will take varying amounts of time to send.

Because characters take different amounts of time to send, and because words have different numbers of characters (although we use five-letters as the average word size), code speed must be based on the sending of a standard word. Two words, “Paris” and “Codex” are used to represent these two standards.

PARIS: This standard, which takes 50 units of time to send (including the space between words) is representative of standard English text; i.e., it takes about the same amount of time to send as the average word. Morse code was purposefully designed so that the more common characters, such as E and T, take the shortest amount of time to send, making the average text flow as quickly as possible.

CODEX: This standard, which takes 60 units of time to send (including the space between words) is representative of words consisting of random letters; CODEX takes the same amount of time to send as the average five-letter word of random characters.

Use the (slower) PARIS method if you want to hear each character at the rate it would be sent in normal English text. Use the (quicker) CODEX method if you want to be writing down random characters at a given rate. We recommend becoming proficient at a given speed using the CODEX method, so when you hear normal English text in a code test, it will sound slower (but you’ll be writing the characters down at the rate you’re accustomed to).

HOW TO LEARN MORSE CODE

One of the first things beginners should do after deciding to learn Morse code is to turn to a reference book and look at the unique dot and dash patterns for each character. Some proponents of quick learning suggest you don’t do this, as it only adds another step in the mental decoding process. Instead, find a convenient tool (there are plenty of Morse code simulators) that lets you learn the patterns by listening to the unique sound for each character rather than decoding a sequence of dots and dashes first and then translating that sequence into words. Once learned in this manner, you will immediately recognize the characters by their sound and not what they look like.

However, if you need a slower method, find a collection of slow Morse code recordings (that come with a key) and listen to the combinations of dots and dashes. As you listen, do your best to picture the letters in your mind as you jot them down. Refer to a Morse code alphabet and translate what you wrote down. Do your dots and dashes make letters? Words? If not, try it again… and again… and again.

Practice translating basic words and sentences into Morse code. In the beginning, you can write it down, then sound it out, but eventually you’ll need to go straight to sounding it out. Start with simple words.

SPACING

Spacing is just as important as the letters that come before and after. Each letter needs to be separated by a space that’s the same duration as a dash (three times the duration of a dot). The better your spacing, the easier your code will be to understand.

MEMORIZE, MEMORIZE

Memorize the easiest letters first. The reason a T is a single dash and an E is a single dot is because they are used most frequently. Start by memorizing the single-dot/dash first and move to the double, and then triple letters. Once you’ve got those down, start memorizing combinations, but leave the more complex combinations for last, which fortunately includes some less commonly used letters (Q, Y, X, and V).

MAKE ASSOCIATIONS

When memorizing the various letters, sometimes it is good to use association, a mnemonic device used to make sound associations between two seemingly unlike things. For every letter, think of a memorable sound that mimics the Morse sequence. For example, C is dah-dit-dah-dit (dash dot dash dot). Consider “catastrophic,” which has an emphasis on the first and third syllable, and begins with a C. A great mnemonic that has been used for years (picture the opening few minutes of “The Longest Day”) is the dot-dot-dot-dash sequence used for the letter V. The sound has the same cadence as the opening salvo of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony.

METHODS OF LEARNING IT: SLOW IT DOWN

Farnsworth Method

The classical way to learn code is to start slow and then build up to a higher speed.

Using Farnsworth timing (developed by Donald R. Farnsworth in the late 1950s), characters are sent at the same speed as at higher speeds, while extra spacing is inserted between characters and words to slow the transmission down. The advantage of this is that you get used to recognizing characters at a higher speed, and thus it will be easier to increase the speed later on, but you have more time between letters. Starting with a slow word speed, you have time to think about the characters, while gradually increasing the word speed as you improve.

Morse Code Tree

Another method to learn Morse code without having to memorize the code table is the Morse Code Tree, developed based on the number of dots or dashes in each letter related to every other letter. Starting at the top, listen to a single letter of Morse code. If you first hear a dot, go to the left; if you first hear a dash, go to the right. For example, dash-dot-dot is sent. Start at the top. When you hear the dash, move to the right to the T. Then you hear the dot, so you move to the left to the N. When you hear the final dot, move to the left to the letter D. Since there is a longer pause at the end of the sequence, you know it is the end of the letter. Move on to the next.

Koch Method

With the Koch Method, you start with an initial set of two characters. Practice listening to random code containing only these two characters. Listen to the characters at your target speed. When you can copy this code at your target speed with 90 percent accuracy, then add a third character to the set. After this new character is added your overall accuracy will go down at first and will then build back up. When you can copy code containing these three characters with 90 percent accuracy, then add a fourth character…and so on.

With this method, you don’t start with the least-frequent letters (E and T) as they will come much easier, but instead start with more difficult letters, like K, Q, and M.

CONCLUSION

If you think that there’s no way Morse code will ever be useful in your life, remember the story of Admiral Jerimiah Denton, the senior-most American POW in Vietnam, from 1966 to February 12, 1973. Throughout his captivity at the infamous Hanoi Hilton, he was mercilessly tortured and given threats of further torture if he didn’t respond correctly to the journalists’ questions at a televised interview scheduled to appear on American TV on May 17, 1966. From the beginning of the interview he feigned sensitivity to the lighting of the cameras and of those in the room, but all the while resisting the Viet Cong propaganda, he was covertly blinking his eyes in Morse code: “T-O-R-T-U-R-E.” Since the North Vietnamese weren’t familiar with Morse code, they were unaware of the messages, and this was the first confirmation that Americans were being tortured.

Since the fading of the requirements to learn Morse code and an increasingly heavy reliance on electricity-based communication systems, fewer people have taken the time to develop this very useful skill. In an age of rapid communication and texting, Morse code is going the way of the carrier pigeon and smoke signals; instead, this antique technology can be used in urgent situations where communication without advanced technology would be crucial. Being prepared by knowing Morse code provides a sense of security that another communication method is only a finger tap away.

Get a Coach and Practice

Many amateur radio stations transmit Morse code practice sessions for the benefit of people learning how to read Morse code or those that want to improve their speed and/or accuracy. Best known are the W1AW radio station’s code practice transmissions and are most widely used. They are located at the headquarters of the American Radio Relay League (ARRL) headquarters in Newington, CT and they provide a very detailed schedule on their website. They offer a wide variety of sessions and can be found at http://www.arrl.org/code-practice-files.

Editors Note: A version of this article first appeared in the February 2015 print issue of American Survival Guide.