RECALLING AN ENCOUNTER WITH A MASSASAUGA SNAKE THAT RESULTED IN A THREE-DAY ORDEAL

In 1972, I was 15 years old and had been an after-school fur trapper since age 12. Many adults regarded my fascination with nature as unnatural. They said, “Boy, you can’t be in those woods all the time.”

I persisted against their advice. Because typical teenagers prefer other activities, most of my outings were solo. That was okay because being alone meant being quiet, and seeing more cool things. But being alone also got me into a few scrapes, like the one I experienced that June.

A NIGHT TO REMEMBER

I’d been out for four days, camped atop a ridge that was bordered by swamp. The nearest paved road was three miles distant. Unwisely, I hadn’t told anyone where I was going; teenagers are notoriously lacking in foresight.

Shelter was a lean-to; I’d had enough trouble from the tents of that era to spurn them. My bedroll was a Korean War mummy bag filled with chicken feathers. It wasn’t better or warmer than my wool blanket, but it was lighter and it was my first real sleeping bag.

I returned to camp that evening and prepared supper in a saucepan. A breeze kept the mosquitoes tolerable as I sat next to the firepit, sipping coffee from a canteen cup. I began to nod off, and I knew I’d best hit the sack before the night chill awakened me with hypothermia.

I dumped the last swallow and hung the cup from the shelter’s frame. The sleeping pallet of branches padded with bracken ferns felt luxurious as I slid into the bag.

Then I felt a stabbing pain on my left ankle, near the Achilles tendon. Dismissing it as a stick, I shifted my foot. The pain persisted, and a burning sensation spread through my calf. I wasn’t concerned until I felt undulating movement against my thigh. I lay still as it slithered across my torso, and an 18-inch snake exited across my left shoulder.

I whipped open the bag, pulled off my sock, and rebuilt the fire. I hoped to find the crescent-shaped imprint of a northern water snake, which has sharp teeth, but no venom.

No such luck. Paired puncture marks near my malleolus (ankle bone) grew puffier even as I examined them. I’d been bitten by a massasauga, the only rattlesnake in Michigan.

“I lay still as it slithered across my torso, and an 18-inch snake exited across my left shoulder.”

I knew about the traditional cut-and-suck method of extracting venom, but the bite was close enough to the tendon that I’d risk hamstringing myself. And besides, I was incapable of reaching the location with my mouth.

The question now was how severe my reaction would be. I’d read that some rattlesnake bites were “dry” with no venom, which is released voluntarily and takes time to replenish. Cursed with youthful optimism, I believed that because I wasn’t ill, I wasn’t going to be. I slid back into my bag and went to sleep.

A FALSE SENSE OF CALM

I awoke feeling rested. My left ankle was swollen and sore when I stomped apart lengths of wood for the breakfast fire. But the fang holes, surrounded by a discolored bruise, seemed to have caused no real harm. Feeling a bit too cocky, I went about my business as usual.

By noon I’d begun to feel ill – sweating, with a slight case of nausea. I blamed it on the heat. Then the poison hit me with a vengeance, dropping me to my knees with shivering and abdominal cramps.

At the onset, I should have headed for home 6 miles away, but now it was too late. Diaphoretic and near collapsing, it took all my strength to drag myself under the lean-to. With boots still on, I pulled the mummy bag over my shaking body. My last thought before losing consciousness was that I’d really screwed up this time.

“My last thought before losing consciousness was that I’d really screwed up this time.”

When I awoke again, it was night. Over the fever-induced ringing in my ears, I could hear the constant whine of mosquitoes. In my mind, their humming coalesced into a single giant mosquito with a saber-length proboscis that probed for an opening through which to drain my lifeblood. This imagined monster seemed so real that I shrank deep into the bag, covering my head as I awaited the fatal stab. Blessedly, I slipped back into unconsciousness.

When I next awoke it was late afternoon, judging by the sun, and I was horribly thirsty. I had two GI canteens and two gallon jugs filled with spring water. I guzzled the contents of one canteen, then passed out again.

Days and nights passed in a blur. One night, friends appeared, calling my name. When I answered them in a croaking voice, they seemed not to notice. At some point, I realized that they weren’t really there. I was still alone in the woods, very sick and very helpless.

I must have drunk both gallons of water. I recall urinating once, rolling onto my side to face the doorway, too weak to rise, then passing out again. I don’t believe I urinated while unconscious, but my sleeping bag was so soaked with foul-smelling sweat that I wouldn’t have been able to tell if I had.

SO CLOSE AND YET SO FAR

It was late afternoon of what I later learned was my third day when I awoke and decided that I wasn’t going to live through this – most rattlesnake victims conclude that they’re going to die at some point during the ordeal. What scared me most was that I’d never be found; I’d be one of the outdoorsmen who even today continue to disappear in northern Michigan’s forests. To my befogged mind, that was more terrifying than the thought of dying.

Fear motivated me to shakily get to my feet. I belted on my last canteen, then started walking unsteadily toward the nearest dirt road, a mile away. I hiked probably a mile after reaching that uninhabited dead-end road, then reached for my canteen only to discover that I’d already drunk it dry. My mouth felt like sandpaper, and my tongue seemed swollen to twice its size. I wanted a drink of water more than I’d ever wanted anything.

There was a stream a few hundred yards ahead. My feet bogged in the loose sand, but thirst drove me onward. Then I was standing atop the creek bank, looking down onto the rushing water and wondering how to reach it. I was only a few feet above the stream, but the bank seemed like a precipice.

Suddenly I found myself lying face down in the gravel-bottom stream, 6 inches of frigid water swirling around my prone body. The cold water cleared my head a bit. Lying on my belly (unwisely, because some dehydration victims have passed out from shock and drowned), I drank until my thirst was slaked. Refilling my canteen seemed like a labor of Hercules, so I left it empty in its cover.

After an unknown length of time, I rose unsteadily to my feet. On the opposite bank stood a gray-haired woman, staring at me with her mouth open. I shut my eyes tightly, thinking that she must be a hallucination. When I looked again, she was still there. There was a seldom-used trail leading to the stream from the other side, and she must have followed that.

“Is that water safe to drink?” the woman asked.

She couldn’t have known that I’d have drunk sewer water in my present state. The important thing was that she was real and I was saved. With renewed vigor, I clawed my way up the muddy bank and rose on shaking legs. The lady retreated with each step I took toward her.

“I tried desperately to tell the woman about my plight, but my tongue was thick and sandpapery, and my own ears heard gibberish issue from my mouth.”

I tried desperately to tell the woman about my plight, but my tongue was thick and sandpapery, and my own ears heard gibberish issue from my mouth. At that, the woman looked near panic, aware that there was something wrong about me, yet failing to grasp that I was deathly ill. The more frantically I tried to explain, the more she backed away. Then the woman was joined by a gray-haired man, who took her arm and led her away.

My heart sank to my toenails. I was less than halfway home, and now feeling more forlorn and hopeless than ever. I climbed back onto the two-track and resumed walking.

I recall nothing of the journey after that, though I must have traversed 3 miles of wooded footpath. I remember bursting through the back door of my house. I careened off walls and doorjambs, knocked over a lamp, and collapsed onto the nearest bed. My mother, siblings, and an uncle gathered around. They bombarded me with questions about what was wrong, and about where I’d been the past week. I managed to utter “snakebite” before again lapsing into unconsciousness.

THROUGH THE WOODS AT LAST

My last word had been understood. My mother called an elderly local doctor with the memorable name of Dr. Van Dillon, who was intrigued enough to make a house call. The old M.D. had resided in northern Michigan since main streets were dirt and most men were lumberjacks. He was familiar with massasauga bites. He inspected the wound, checked my vitals, and pronounced that I had already seen the worst of it. His advice was to let me sleep it off.

I awoke three days later, feeling terrific, except that I was ravenously hungry (my shrunken stomach wouldn’t accommodate more than a couple of mouthfuls), and I couldn’t seem to get enough to drink. I’d lost eight pounds, probably most of them due to dehydration.

My experience was fairly typical of pit-viper bites. Most healthy individuals will survive an intramuscular bite without medical help. Some southwestern American Indian tribes once made a practice of being ritualistically bitten to induce visions. Like I did, they recovered from the experience feeling great.

Once was enough for me. I harbor no animosity toward snakes, but learned to never leave my bedroll open to intrusion by small animals. My snakebite ordeal is one of my most cherished memories, but I sure as hell don’t want to do it again.

SNAKEBITES:

HOW TO AVOID THEM AND HOW TO TREAT THEM IF YOU CAN’T

Avoidance

Think like a snake: you’re smaller than most predators, slower than your enemies, and you have no weapons except the venom in your fangs. Some poisonous species, like the coral snake, have no fangs and must bite down to force envenomation. For that reason, you seek out holes and recesses where you feel secure, though you’re sometimes caught in the open, while warming your cold-blooded body in the morning and afternoon sun.

Poisonous snakes are loath to bite anything they can’t eat; they will always try to withdraw from confrontation, and never strike without warning. The golden rule of bite avoidance is to take one step back. Even if a snake is unusually aggressive – a female about to lay eggs or give birth – pursuit is slower than a fast walk, and ends when a perceived threat has withdrawn a few yards from the snake’s claimed territory.

First Aid

Most snakebites occur on extremities, the hands and forearms more than the legs. The body’s immediate response to the wound is ischemia, a restriction of blood vessels around the wound site that helps to keep venom localized. Prompt application of suction from a venom extractor helps to remove injected poisons before they reach the bloodstream.

- Apply a proximal tourniquet made of a belt, rope, or elastic bandage (preferred) around an affected limb to retard blood flow, and venom, to the heart. The ideal tourniquet should not be so tight as to cut off blood flow, as this could damage the limb. The American Red Cross suggests that tourniquets be loose enough to get one finger under them.

- DO NOT use the cut-and-suck technique to try to remove injected venom; doctors are almost unanimous in their opinions that adding trauma around a bite area does more harm than good. If possible, keep the bite area lower than the victim’s heart, using gravity to help minimize the spread of venom. Splint the elbow or knee joints of bitten limbs to keep them from flexing and acting to pump venom from the bite site.

Outcome

Approximately 7,000 to 8,000 people are bitten each year by 20 species of poisonous snakes that are native to every state except Alaska, Hawaii, and Maine. Of these, only about five people die from the experience.

Often the first strike is a “dry” one, a warning.

“Some 20-30% of patients we see who have been bitten by a snake, who actually have fang marks, have not received any venom at all,” says Dr. Edward L. Hall, M.D., a snakebite expert from Georgia. If a snake is provoked into striking a second time, it’ll probably not be so merciful.

More important than even first aid is getting bite victims to an emergency room within 30 minutes. There have been rare cases of allergies to antivenoms derived from horses, but as Don Tankersley, deputy director emeritus of the FDA’s Division of Hematology, has stated, “You’re treating a life-threatening situation. It’s clearly a case of weighing the risks versus the benefits.”

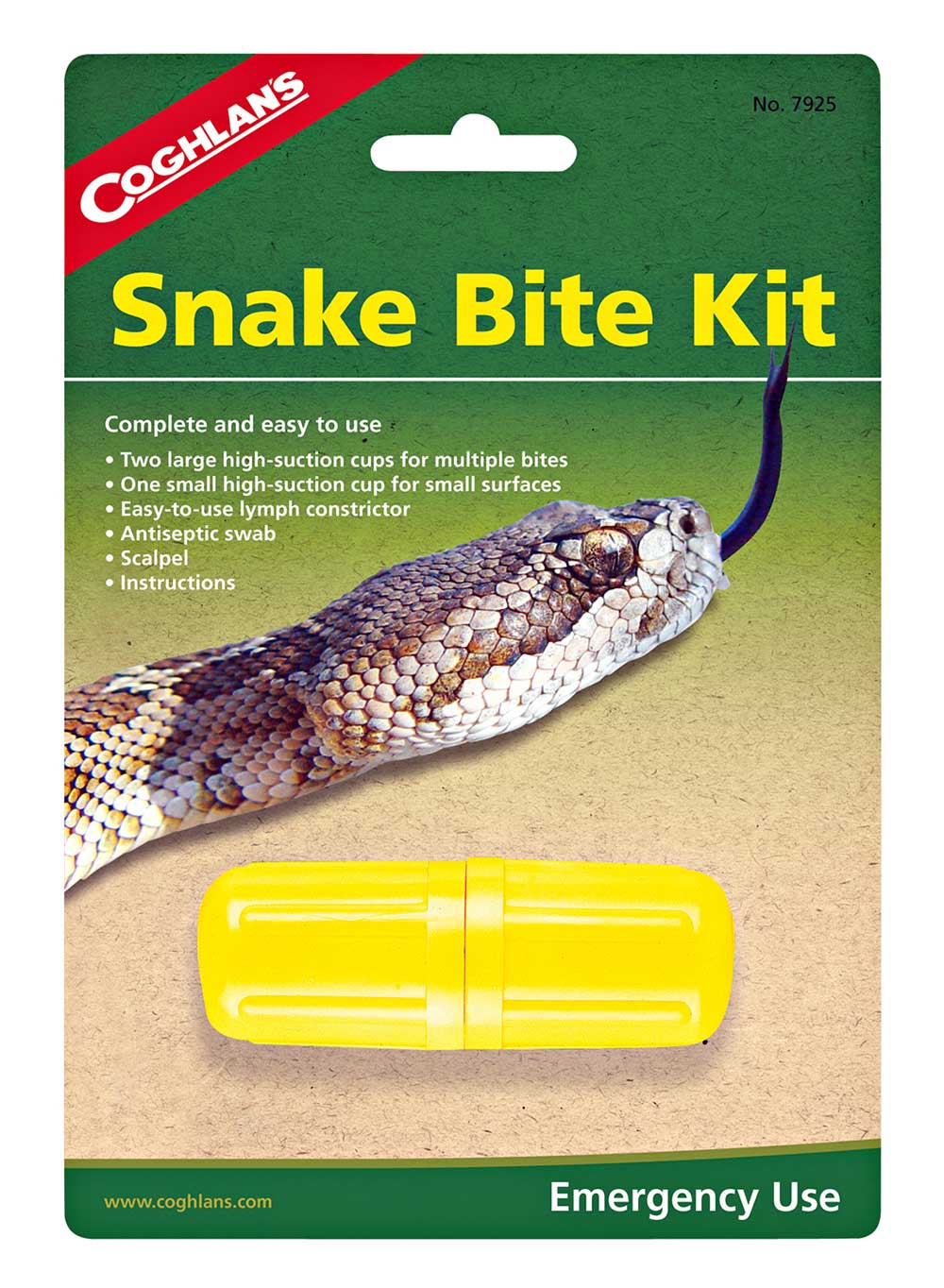

SNAKEBITE KITS THAT SUCK

A lot has changed since snakebite kits consisted of a Bowie knife and a strong stomach. Modern medicine has spurned the old cut-and-suck technique in favor of suction extractors that draw snake, spider, scorpion, and bee venom from the same holes in skin that were made when the poison was injected.

Opinions about venom extraction kits are as varied as the people who use them. Dr. Sean Bush, M.D. is one medical professional who voiced his disapproval publicly in a paper titled “Snakebite Suction Devices Don’t Remove Venom: They Just Suck.” That sentiment is echoed by a number of doctors and laymen alike.

In fact, it appears that most detractors of vacuum-type extractors may be expecting too much from the simple device. Tissue damage caused by extreme suction against the epidermis is too well-documented to deny, and it’s known that extractor syringes can only remove some of the venom that a rattler drives deep into a victim’s muscle.

An analogy for a rattlesnake bite is hypodermic injection. It would be unreasonable to think that a substance injected under pressure deep into living tissue could then be drawn back out the way it came. You might get some of it, but a large percentage gets into the surrounding capillaries, and from there into a recipient’s system.

“The main thing is to get to a hospital and don’t delay,” says Dr. David Hardy, a noted authority on snakebite epidemiology. His sentiments are echoed by the American Red Cross and most medical professionals. They generally concur that the quicker you apply suction, wrap a restrictive bandage, and get the victim to an emergency room, the less traumatic the experience. Should you have a snakebite kit in snake country? By all means. But use it swiftly when needed, and don’t expect miracles.

A version of this article first appeared in the August 2022 issue of American Outdoor Guide Boundless.