Sometimes the worst begins on the most regular of days.

Sometimes the worst begins on the most regular of days.

Imagine a family of four on a typical school day morning. They get dressed, eat breakfast, watch for the school bus, and head off to work. But by mid-morning, mom isn’t feeling well. She has chills, muscle pain, and a sore throat. It’s the flu, it seems, which she finds strange, because she had her annual flu shot a month ago. Yet many of her co-workers have been sick, too.

Mom goes home to rest, but by the end of the day she’s worsening. Within a week, the entire family is sick. It’s then that things begin to spin out of control. Mom’s respiratory distress becomes severe, but she’s turned away by her doctor’s office, because they’re overloaded with flu patients and have no more antiviral medication. In the Urgent Care waiting room, rows of people hack and wheeze. Some are sitting or lying on the floor. Rumors spread that this is bad— really bad—and that people are getting pneumonia and some are dying from respiratory complications. Not only those in high-risk populations, like the elderly and ill. Everyone is at risk.

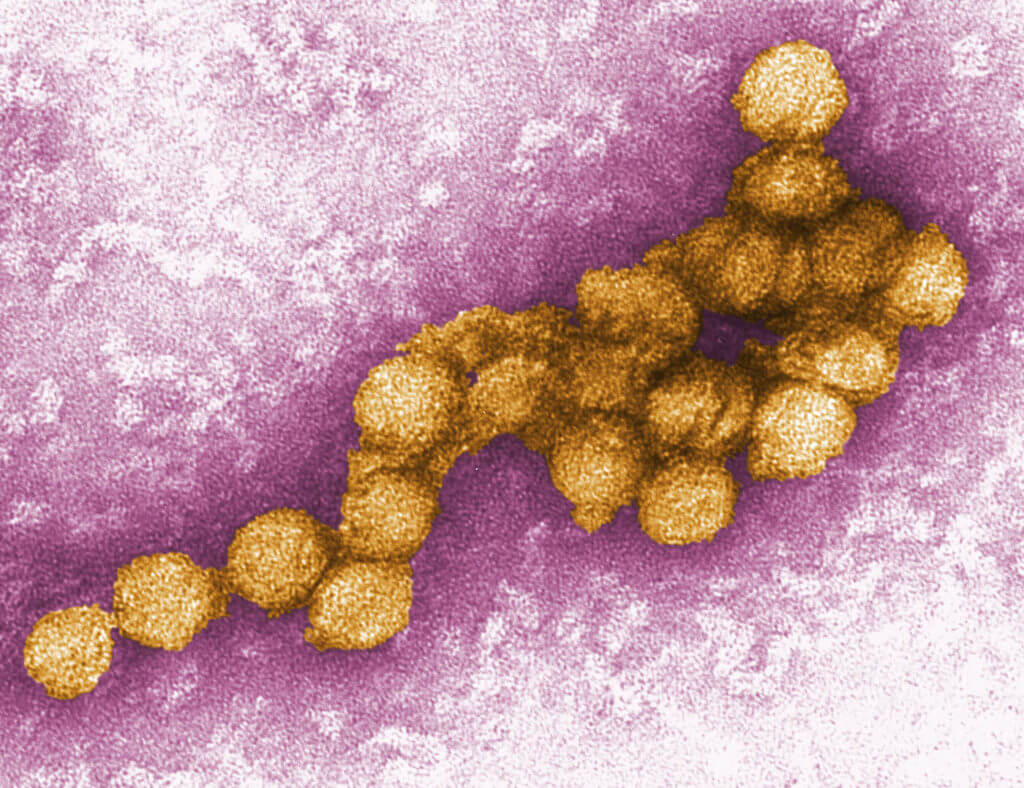

Message boards, blogs, and forums permeate the internet, propagating a wave of mass hysteria. Yet public health officials try to keep things under control. Calmly, they describe the facts. It appears that a new influenza A virus has emerged. Often called the “bird flu,” because it is carried by wild aquatic birds like ducks and gulls, it’s what causes seasonal flu epidemics. But in this case, scientists haven’t seen this particular strain before, which means the human population hasn’t had previous exposure to the virus and virtually no one is immune. Current flu shots won’t help. The virus is very contagious. Young, healthy people are at risk. Cases are popping up in various countries around the world.

Of course, measures are being taken. Scientists are working diligently to develop an effective vaccine, but no one can predict when it will be complete. Drug companies are making more antiviral medication. Travel restrictions and bans have been issued in order to contain the spread of the virus. Schools are closing down one by one, both in order to protect students and staff, and also so the buildings can morph into makeshift clinics. In the meantime, citizens are asked not to panic.

What Causes a Pandemic?

This scenario describes a realistic example of a flu pandemic, a rare global epidemic where an infectious disease moves quickly, affecting huge numbers of people in a short period of time, spanning state lines and borders, crippling the economies of highly affected nations, and creating large scale serious illness. Unlike an outbreak, which we hear about regularly on the news and find listed on the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) website—diseases or natural disasters that are contained to a certain country or region like the recent enterovirus D68 in the U.S. or the Washington Oso mudslide—the global nature of a pandemic puts enormous strain on healthcare and government systems around the world, because mass illness means a shortage of hospital beds, ventilators and other life-saving equipment, supplies, and health care professionals.

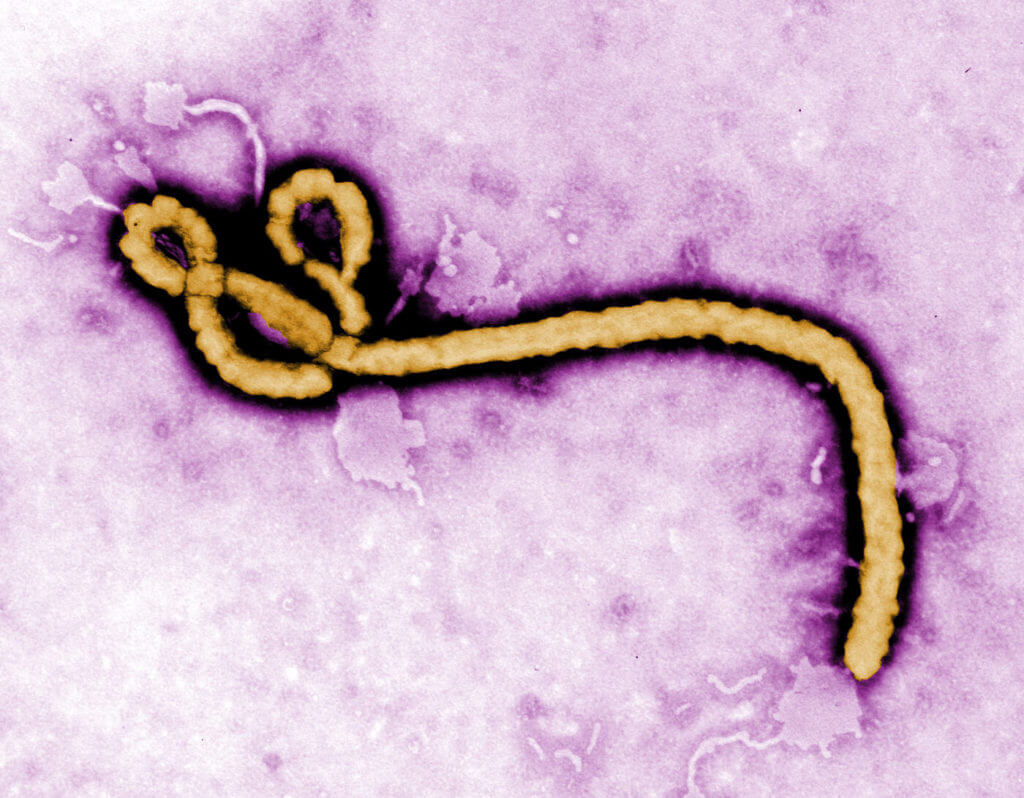

Fear and panic are key factors in a pandemic. So are the tricky properties of viruses. They are unpredictable, sometimes lying dormant for months or years without causing illness. Or they unexpectedly mutate—change form—into a new, unfamiliar version that scientists haven’t seen, meaning there’s no vaccine. Maybe the new version transmits in a new way, such as through the air instead of only through bodily fluids, causing extra cause for alarm. Or the virus doesn’t respond to medication. Perhaps it preys on the immune systems of perfectly healthy people—the prime gene pool— instead of the sick and elderly. There are so many possibilities.

Because of this, the reality is that public health officials agree that a future pandemic— and the flu is a major concern—isn’t a matter of if, it’s a matter of when. One must only look back at history to see the reason for this prediction. Various examples come to mind. For starters, in 1918, the notoriously deadly H1N1 flu pandemic infected 500 million people across the world with incredible endurance, traveling even to highly remote locations like the Arctic, attacking the immune systems of primarily healthy young adults. The U.S. death toll alone was 675,000. Theories on how the pandemic began are varied; a couple of investigations point to Kansas. Another to China. British virologist John Oxford speculated that the virus originated in a troop camp in France, harbored in birds and then mutating to pigs, which were kept at the camp; eventually transmitting and causing aggressive illness in humans.

More recently, the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, commonly called the swine flu, comes to mind. Originally thought to be an outbreak confined to Veracruz, Mexico, this strain never seen before in humans was detected in April 2009 in a 10-year-old patient in California. More cases were diagnosed in California, and then beyond, and by June the World Health Organization had declared an official pandemic. According to the CDC, in a one-year time span, the pandemic caused approximately 60.8 million infections, 274,304 hospitalizations, and 12,469 deaths in the U.S. alone.

Other Diseases

But pandemics are not limited to only the flu. Consider, for example, human acquired immunodeficiency virus (HIV/AIDS). Although the origins of the virus can be traced back to Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in the 1920’s, the first cases weren’t reported until 1981. HIV has been a particularly perplexing virus for scientists to understand because it lies dormant in infected individuals without causing symptoms, sometimes for many years. Before public education campaigns were developed and HIV testing became widespread, people were unknowingly spreading the virus widely, often through sexual contact or by sharing needles during recreational drug use. This caused the pandemic to grow to alarming proportions. As of 2006, the CDC reported more than 65 million cases of the infection and 25 million deaths in the U.S. Currently, more than 35 million people are living with HIV around the world.

BioWarfare

The other important factor in speculating about the potential for another pandemic is that Mother Nature isn’t the only culprit. Biological agents, including bacteria and viruses, have been used in acts of biowarfare and bioterrorism throughout history. These terms refer to the deliberate release of a biological agent into the air, water, or food, with the intention of sickening and killing large numbers of people. As far back as 450 B.C., Scythians archers, who ruled a vast region around present day Iran, concocted a mixture of decomposed bodies of venomous snakes, human blood, and manure, and allowed it to putrefy. They dipped their arrows into this concoction that contained the bacteria of gangrene and tetanus, among other things, and then shot these arrows at their enemies.

The other important factor in speculating about the potential for another pandemic is that Mother Nature isn’t the only culprit. Biological agents, including bacteria and viruses, have been used in acts of biowarfare and bioterrorism throughout history. These terms refer to the deliberate release of a biological agent into the air, water, or food, with the intention of sickening and killing large numbers of people. As far back as 450 B.C., Scythians archers, who ruled a vast region around present day Iran, concocted a mixture of decomposed bodies of venomous snakes, human blood, and manure, and allowed it to putrefy. They dipped their arrows into this concoction that contained the bacteria of gangrene and tetanus, among other things, and then shot these arrows at their enemies.

The first recoded “weaponized” biological agent in North America—smallpox—was used during the French and Indian Wars in the mid 1700s. The commander of British forces in North America formulated a plan to “reduce” the size of the Native American tribes that were hostile to the crown, so in late spring 1763, when there was an outbreak of smallpox in the garrison of Fort Pitt, blankets and a handkerchief were used to collect the pus or dried scabs from the smallpox sores of the infected British troops and were then ceremoniously given to the Indians. Native American tribes in the Ohio Valley suffered a smallpox epidemic.

And much more recently, there have been acts of terror involving biological agents that concern officials. For example, in the Rajneeshee bioterror act of 1984, salad bars in 10 restaurants in Oregon were deliberately contaminated with salmonella by followers of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, sickening 751 people and hospitalizing 46. The anthrax attacks after 9/11 also come to mind, as does the fact that ricin has been sent through the mail to political figures in the last year. Because of events like this, contamination of public food and water systems, and the use of the postal system to disseminate pathogens, remain a top concern, and public health and biosecurity experts are always asking the question, “Could this be done on an even larger scale?” They spend a lot of time in committees brainstorming possibilities. What if terrorists drop a bomb containing smallpox into the middle of a city? What if anthrax is released into the air in a subway station?

As a result, after 9/11 and the subsequent anthrax attacks, the CDC pooled its resources and went to work developing a list of the biological agents that are potential threats in an act of bioterrorism. They put them into categories based certain factors: their ability to be easily disseminated, cause public fear and panic, result in widespread illness and death, and ultimately cripple the infrastructure and economy of a society. Category A agents— those that pose the greatest threat—include anthrax, smallpox, tularemia, botulism, pneumonic plague, and the viral hemorrhagic fevers, which includes Ebola. To make matters worse, acts of bioterror create not only a public health emergency, but a biosecurity issue that requires an even deeper level of resources, investigation, and surveillance

How to Prepare

In looking back at historical events, the good news is that we’ve learned a lot from what’s already happened—both through Mother Nature and through deliberate acts—which have helped take steps toward preparing for the future. Strides have been made. For example, scientists understand the HIV/AIDS virus more clearly, and drugs have been developed which treat symptoms, improve quality of life, and increase life span for infected individuals.

In addition, screening for HIV has become the norm in U.S. culture, and communities around the country have dedicated time and energy to raising awareness; educating people about how to prevent infection and transmission of the disease by practicing “safe sex,” such as using condoms.

In terms of the flu and the potential for another pandemic, the CDC has come up with simple ways to prevent infection and transmission. Four everyday recommendations that people can implement include getting an annual flu vaccine, covering your cough, washing hands often, and taking antiviral drugs if you become ill and your doctor recommends them. Hospital preparedness for large-scale illness has also been a major focus. Post 9/11, the Bush administration and future leaders have allocated increased funds to helping healthcare systems. This has meant purchasing more hospital beds and equipment, developing committees that discuss evidence-based protocols and procedures, and creating coalitions; partnerships between neighboring hospitals. Healthcare systems are required to practice mandatory drills, in which hospital communications staff announce a disaster, and volunteer patients arrive at the hospital and may be suspected of having been infected with smallpox or anthrax or Ebola. The front line doctors, nurses, and staff respond as if it were a real situation, containing the contagious patients and initiating a series of steps of decontamination; ultimately preparing for a real situation.

Hospital preparedness for large-scale illness has also been a major focus. Post 9/11, the Bush administration and future leaders have allocated increased funds to helping healthcare systems. This has meant purchasing more hospital beds and equipment, developing committees that discuss evidence-based protocols and procedures, and creating coalitions; partnerships between neighboring hospitals. Healthcare systems are required to practice mandatory drills, in which hospital communications staff announce a disaster, and volunteer patients arrive at the hospital and may be suspected of having been infected with smallpox or anthrax or Ebola. The front line doctors, nurses, and staff respond as if it were a real situation, containing the contagious patients and initiating a series of steps of decontamination; ultimately preparing for a real situation.

And science continues to leap forward as well. Partially with government funding, virologists at major universities have been studying biological agents of concern, including emerging viruses; gaining ground in understanding their properties and behavior. In addition, some researchers are partnering with pharmaceutical companies to create effective vaccines and antiviral drugs that can be stockpiled for use in case of emergency. They are constantly working to predict what might be needed next.

With all that has been learned and with ongoing efforts in place to improve current emergency protocol—some of this gleaned from the mistakes that have been made in the current Ebola crisis—the good news is that many experts believe we can survive a future pandemic. In her recent book Scatter, Adapt, and Remember: How Humans Will Survive A Mass Extinction, science writer, Annalee Newitz, captures this spirit of survival when she says, “The world has been almost completely destroyed at least half a dozen times already in Earth’s 4.5-billion-year history, and every single time there have been survivors.” Thus, if we’ve done it before, we can do it again. She cites examples of how organisms in nature have survived harsh conditions—from cyanobacteria to gray whales—and how we can learn from them. In addition, she discusses how ancient tribes of humans, specifically Jews, learned to survive war and oppressive conditions by dispersing and creating new communities.

On the ground in society, the CDC provides comprehensive plans for how specific groups— businesses, communities, parents, schools, travelers, and health care professionals—can prepare for a future pandemic. For example, a five-step practical plan is suggested for reducing the flu in schools. Recommendations include encouraging staff and students to stay at home when they’re sick; covering noses and mouths when sneezing or coughing; avoiding touching your nose, mouth, and eyes to avoid the spread of germs; washing hands often; and disinfecting surfaces and objects.

Surviving a Global Pandemic

There are important ways for individuals to prepare, too. According to the Emergency Preparedness Center, an online resource focused on practical solutions post-disaster, the best way to survive a pandemic is to avoid getting sick. Which means avoiding sick people. This may sound obvious, but preparation for “avoiding people and society” requires forethought, and it’s important to develop a comprehensive plan—focusing on both skills and gear—that is appropriate and your family. Here are some tools to get started.

Building Self-Sufficiency

If the pandemic is prolonged, which is a strong possibility (remember the 1918 flu), it’s a good idea to plan for societal shutdown. Sick people aren’t going to be at work, and those who aren’t sick may be at home caring for ill family members. Many businesses may close.

It’s important that you and your family are able to live comfortably in your home, so that you can implement your own form of social distancing. Recommendations include:

- Ideally, choose to live in a less populated or rural area

- Install alternative power sources in your home, such as solar panels and shingles

- Store several battery-operated lanterns

- Consider having a propane heater (and tank) on site

- Store a radio with extra batteries in order to listen to news updates

- Don’t forget entertainment. If you’re stuck inside your home for a long time, you’ll want things to do. Collect books, games, craft projects, and other activities you and your family enjoy. Especially with children, it will be important to make sure there is plenty to do.

Food and Water

If grocery stores shut down, or if the water supply becomes contaminated, you’ll want to make sure you have sustenance.

- Approach food stockpiling little by little until you have about a month’s worth of food stored. Each time you go to the grocery store, buy few extra items; preferably things you are already used to eating. Store them in your pantry. If you have children, engage them as you choose what to buy.

- Plant a garden. Even small plots produce a significant amount of food. Depending on the time of year, you may be able to eat straight out of your garden. If you live in a place that doesn’t have a year-round growing season, learn how to can fruits and vegetables and then add them to your stockpile for the winter.

- Learn basic cooking skills, and involve your children.

- Stores water in your pantry. In addition, fill empty jugs with water and put them in the fridge and freezer. In addition, make sure you have a reliable method for sterilizing tap water, if this becomes necessary.

Medical Considerations

In the case of a pandemic, hospitals will be overloaded, and you won’t want to go near them, in order to avoid exposure. Plan in advance for what you might need.

- Make sure you have a current medical history on each family member

- Keep extra medications on hand for family members who suffer from chronic conditions. Don’t forget important toiletries like contact lens solution, toilet paper, and paper towels.

- Make sure you have a first aid kit that includes basic supplies for cuts, bruises, and minor injuries

- Take a CPR and First Aid class to build your skill set

Preparing for the Flu

Since a flu pandemic is one of the greatest threats, the Emergency Preparedness Center lists the following steps to take, in case you get sick.

- Build up a supply of over-the-counter medications like ibuprofen, acetaminophen and cough suppressants.

- Stock up on energy drinks for rehydration and replacing lost electrolytes.

- It’s also good to have a supply of rubbing alcohol, disposable tissues, and a thermometer.

- If you are planning to travel, you can track flu trends here.

Editor’s note: A version of this article first appeared in the Doomsday 2016 issue of American Survival Guide.