A HUNTER COMES FACE-TO-FACE WITH A BLACK BEAR

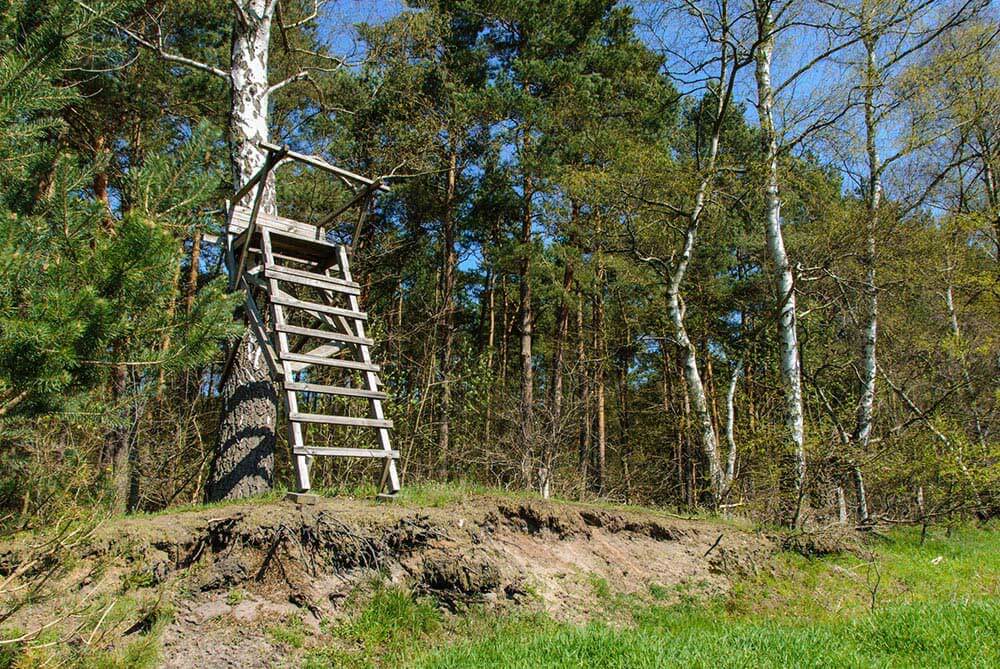

It was barely dawn, but already a sweltering July sun beat hotly against the flat, densely forested swampland near Hiawatha’s Tahquamenon River, in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Squadrons of bloodthirsty deerflies and almond-sized horseflies kept me awake as I sat in silence, 4 feet above the ground on a portable tree seat.

A 400-pound male black bear had already passed by 50 feet downwind of my hide, casting sidelong glances at the veil of leafy branches that concealed me, but preferring, as black bears normally do, to avoid contact with humans. I was glad he did, because it was the middle of mating season, the time of year when territorial, testosterone-drunk dominant boars were least predictable.

Betty4240 / Dreamstime.com photo

I was studying the brush where that big boar had disappeared when I was jolted to alertness by the snap of a stout dead twig breaking under heavy pressure to my immediate right. I remained absolutely still, hardly daring to breathe, as a black bear sow weighing about 250 pounds ambled casually past me, not 5 feet from the tree where I was sitting. She seemed completely unaware of my presence, despite being close enough to spit on. I let her travel about 75 feet before raising my preferred off-season hunting weapon, a 35mm SLR camera with 70-210mm zoom lens.

“With each metallic click, the curious bear drew closer to my hiding place.”

The sow stopped to sniff at the trail where the boar had disappeared into the woods, probably sizing him up as a potential mate from olfactory information in his scent trail, and I began snapping pictures. At the first click of the shutter, the sow raised her head and looked about in apparent puzzlement, nostrils flaring as she smelled for spoor. The shutter snapped again, sounding incredibly loud amid the soft buzzing of cicadas, and the bear started toward me. Her round ears swiveled to pinpoint those alien sounds coming from the forest. With each metallic click, the curious bear drew closer to my hiding place.

WHOA BLACK BEARY

I think I understand how so many combat journalists have become casualties. Even though I was being approached by a wild animal that possessed several times my own physical strength – and was bound to be startled upon meeting me in a few seconds – I couldn’t stop shooting pictures. Exhilaration displaced fear as the bear sat down on its haunches merely 5 feet away, separated from me by only a sparse veil of leaves. I shot another frame as the sow looked around from her seated position, still uncertain about the source of those alien noises. Her head rotated to look directly at my camouflaged face. I froze in fear and anticipation.

Incredibly, the sow still hadn’t detected my presence. She rolled forward onto her feet and stepped through the concealing umbrella of foliage that surrounded me. A shock of adrenaline coursed through my spine when the bear, seeming a good deal larger than it had looked from farther away, stepped up to sniff the trunk of the large poplar tree to which my seat was fastened. I felt an electric shock when her left ear actually brushed against my right boot as she nosed around for odors.

I also began to consider that even a panicked, reflexive slap from this powerful, heavily clawed animal could make the 2-mile hike back to my truck less than pleasant. I’d never been so close to a bear in the wild, before or since, and it seemed appropriate just then to ponder what this powerful bruin might do when surprised at such close range. Since there was really nothing I could do except to find out – and I figured that was going to happen shortly in any case – I focused as sharply as the telephoto lens allowed at such close range, and snapped another picture.

The sow looked straight up at my face, her head framed almost ridiculously between my boots. After a moment of confusion she opened her mouth wide and said, “Waaaaaaa-aaaaa-aaaa.” There must have been tremendous kinetic energy in that sound, because it raised my buttocks several inches above the tree seat.

“There must have been tremendous kinetic energy in that sound, because it raised my buttocks several inches above the tree seat.”

Ralf Neumann / Dreamstime.com photo

Bobhilscher / Dreamstime.com photo

Then the startled bear performed an amazing feat of acrobatics. With an agility that belied her bulk, the sow executed an eye-popping back flip, twisting in midair to land on four paws that were already moving fast in the direction from which she’d come. Swirls of dry leaves displaced by 20 frantically scrambling claws drifted slowly back to earth behind her as the panicked bruin plowed headlong through underbrush. The shutter clicked of its own volition, and I got a blurry picture of the retreating bear.

Back in the open, the sow’s courage and curiosity returned. She stopped about 30 feet from my hide and rose fully erect on her hind legs, nose and ears working furiously while she surveyed the area from that elevated position. I shot one more blurry frame, and then she was gone, disappearing into the shadowed forest along the same path the big boar had taken.

LESSONS TO BEAR IN MIND

A number of lessons can be gleaned from this incident. Foremost is the insight it provides into how aggressive a healthy black bear really is. While I’m grateful that events unfolded as they did, I could hardly have blamed that sow for instinctively swatting me in blind panic, or even mauling me until she was convinced I was incapable of being a threat. But she didn’t; she ran away like virtually every other bear I’ve come upon unexpectedly, using her great strength and mass not as weapons, but as the means to hastily withdraw from a potential confrontation.

Mkojot / Dreamstime.com photo

I hope this experience will offer some comfort to hikers who happen on a fresh bear track or scat and feel anxious about the maker’s whereabouts. Too many filmmakers, novelists and clever taxidermists have depicted the black bear as ferocious and bloodthirsty, but such caricatures are not to be taken seriously. To be blessed with the rare opportunity to observe a wild black bear in its natural habitat is to understand why Native American tribes once knew the species as “Brother Bear.”