These versatile equines could be the key to your survival.

The world is changing, and we need to be prepared for those changes.

More and more people are living life with a “what if … ” frame of mind. Many people are now growing at least some of their own food and raising some livestock. In my neck of the woods, it is very common to hear the sounds of rototillers starting up as soon as the ground can be worked.

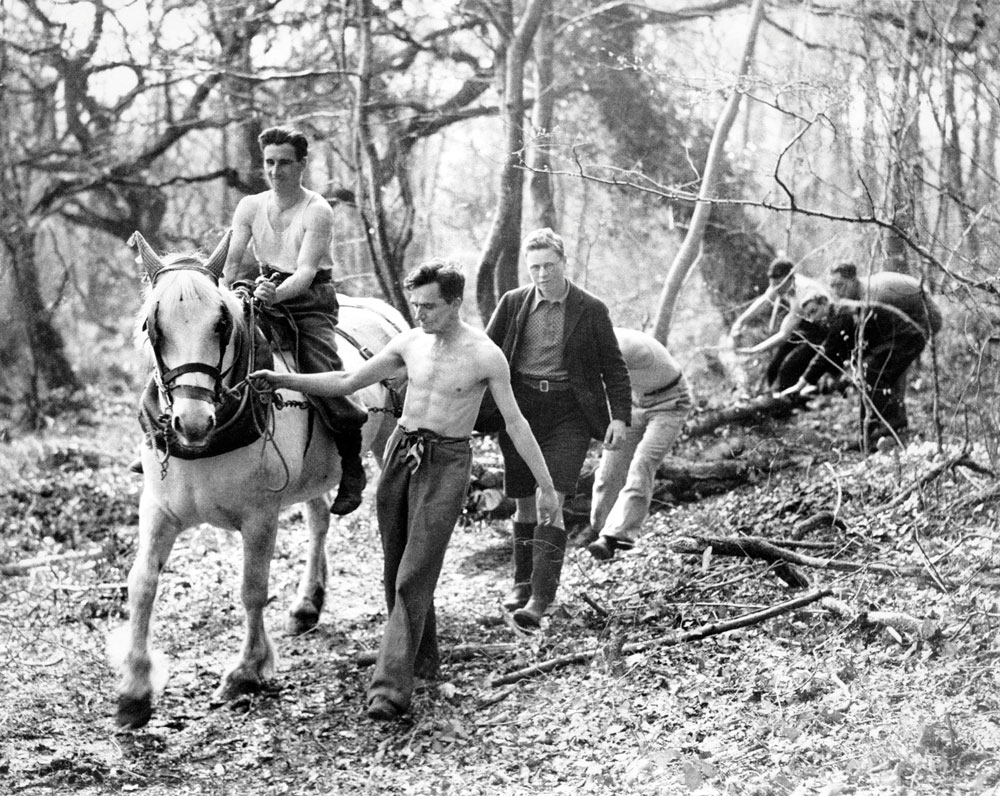

While this is all well and good, what will people do if there comes a time when we have no fuel to run our tillers, mowers, chainsaws and other motorized equipment?

These animals don’t use gas, need oil changes or mechanical knowhow, or run on computers—although they do need care, love and respect. If you give them that, you’ll have a much better chance of becoming self-reliant in a challenging new world.

To answer that question, we don’t need to look any farther back than about 200 years ago to a time when there were no internal combustion engines. Back then, our ancestors relied on horses and oxen to get work done.

This article will examine the historic role horses and ponies have played in human survival—specifically the group known as “heritage” breeds.

“Heritage” and “Landrace” Breeds

Throughout this article, you will see the terms, “heritage” and “landrace,” used fairly often. So, just what do these terms mean, and what makes them so special? According to The Livestock Conservancy, heritage breeds are simply “ … traditional breeds of animals that were raised by our forefathers.”

These are the animals that were being used prior to the practice of industrial agriculture—in other words, before horses and other animals began being manipulated by human-induced cross-breeding in an effort to get larger, stronger or smaller animals and before we bred different animals just to get “the right look and color.” Most of the heritage breeds have superior natural attributes, such as the ability to forage, superior fertility, and resistance to disease and parasites that makes them better prepared for survival.

Landrace breeds are also heritage breeds, but there is a difference. By definition, a landrace breed is a domestic animal that has naturally developed over time, adapting to the natural and cultural environment of a particular area. These animals, just by their location, have also been isolated from other populations of the same species. This means that they have built up a genetic pool uniquely their own. The Newfoundland pony is a great example of a landrace breed.

Why These Animals Are Special

While any horse or pony is capable of pulling a plow or a sleigh, some are better suited to this work than others. Many of the heritage breeds evolved for work—and that is exactly what they did for our ancestors. There are some that worked better as saddle horses than plow horses, but the common link is work. In a survival situation, you’ll want a horse that can do the work you need done to keep you alive.

Heritage breeds tend to be expert foragers and are fully capable of finding food on their own, even during the winter. A long coat of hair keeps them warm, so they can survive with limited shelter. They are naturally disease- and pest-resistant, so there are fewer, if any, veterinarian bills. This is all important in a survival situation: If there is a need to go back to the old ways, vets will be few and far between; and horses, like people, will need to be able to look out for themselves.

Many modern horse and pony breeds are not disease-resistant, have lost the ability to forage, and some might have a greater incidence of complications during the birthing process.

Unfortunately, the very traits that make the heritage breeds so desirable were also the reason for their decline—in some cases, to extinction. Due to extensive cross-breeding practices by people who wanted animals that were bigger, faster, prettier and had other attributes they valued, pure strains of the heritage breeds began to disappear. Unfortunately, with them went many of the good traits that we no longer see, such as their higher fertility rates and disease-resistance. Many modern horse and pony breeds are not disease-resistant, have lost the ability to forage, and some might have a greater incidence of complications during the birthing process.

My Top-Three Heritage Equines

While I love all horses and ponies, draft horses are my favorites (and not just because they pull a beer wagon!). However, if I found myself in a survival situation for which there was a need for a horse or pony, I wouldn’t go with the large draft breeds—I would want a good, all-around horse. It would need to be able to pull stumps and logs out of the woods; pull a sleigh in the winter and a wagon the rest of the year; and it would need to be rideable. Basically, this horse would need to be as versatile as I am and able to do everything my truck does for me now.

The top two horses and pony that I would want if the need ever comes about are all breeds that developed here, in North America: the American Cream horse, Morgan horse, and the Newfoundland pony. All three are considered “working” horses, with the American Cream being a smallish draft horse. Best yet, these three have all the things you should look for in a horse that will be plowing fields and hauling firewood, not riding in a ring and jumping over standardized hurdles (although they can do that, as well).

While any horse or pony is capable of pulling a plow or a sleigh, some are better suited to this work than others.

American Cream Horse: I traveled to Poland, Maine, and visited MerEquus Equine Rescue and Sanctuary. There, I spoke with Kerrie Beckett about the American Cream. There are currently eight American Creams under her care; five are at the sanctuary. This horse is the only draft horse developed in the United States that is still in existence.

The American Cream was once considered a color phase and not a breed, but DNA testing has proven otherwise. Based on its genetics, testing has determined that the American Cream is a “distinct and unique” animal. It is a medium-sized horse that weighs between 1,800 and 2,000 pounds. Its great strength makes it perfect for pulling stumps in the field, hauling logs out of the woods or plowing a field. It can also be ridden.

According to Kerri, American Creams are very docile and calm. They are adaptable to different areas, and they love to work and stay active—a sign of great intelligence. All of this makes them perfect for small farms. According to The Livestock Conservancy, the American Cream horse population is considered to be at the “critical” level, which is the most serious classification of concern for extinction … all the more reason to save this animal.

The Morgan Horse: The Morgan horse is probably one of the most versatile breeds. Early American families needed their horses to be able to perform a variety of functions: strong enough for working in the fields and also quick harness and riding horses. It was developed in Vermont (because I am a New Englander, it has always been one of my favorites).

The natural qualities of this horse made it a desirable starting point for many other breeds, such as the Quarter horse, American Walker, American Saddlebred horse and others. Its qualities also made it a choice for cavalry mounts during the American Civil War.

As with many other horse breeds, the very qualities that made it desirable ultimately became its undoing. After the Civil War, there was a push for larger draft breeds and saddle breeds. Morgan stallions were bred to all sorts of mares, and Morgan mares were often bred to larger draft horses with the goal of producing specific horses that had the desirable qualities of the Morgan.

Small pockets of “original” Morgans still exist in small numbers, mainly in western Vermont. Today, the University of Vermont still has a Morgan breeding program based on those few original animals. Although Morgan numbers are increasing, they are still considered critically endangered simply because there are so few “pure” blood strains left.

The original Morgan horse is a medium-sized animal made to work and weighing between 800 and 1,000 pounds. It is strong, docile and loves to stay active. These horses are known for their large chest and muscled legs. Deep in the Vermont woods, Morgans were known to “out-walk, -trot or -pull any horse.” These horses were used for every purpose you can think of.

Today, there are two separate lines of Morgan horses: Foundation and Non-Foundation. Foundation horses have little to no non-Morgan blood. Non-Foundation horses have much higher percentages of non-Morgan blood. If you are looking for a good, all-around horse to work on the homestead, select a horse from the Foundation line. If you are looking for a beautiful show horse, go with the Non-Foundation line.

The Newfoundland Pony: Some 400 years ago, the English colonized the Canadian Maritime Provence of Newfoundland. The people who call this area home are a tough lot—and so are their animals. They have to be able to survive the brutal conditions of the North Atlantic coast.

The original settlers brought with them animals common in the British Isles, including ponies. Some of these ponies were Welsh Mountain, Scottish Galloway and Highland. When not in use, the ponies would be turned loose in a common pasture, where they more or less fended for themselves until they were needed again. When not working, the ponies did what ponies do, thus beginning the genetic line that became the Newfoundland pony.

Over time, the ponies, like the people they lived with, grew hardier and developed traits that would allow them to survive through the harsh conditions. Those that could not adapt died. Surviving ponies developed strong legs and large hooves for traveling over the rocky terrain. They developed resistance to many diseases, and they could eat almost anything that resembled a plant. In other words, they were tough. And this was all done through natural selection.

Today, the Newfoundland pony is also on the verge of extinction. There are fewer than 400 “pure” Newfoundland ponies worldwide, with 40 of them being in the United States. Many of these animals are gelded males, as well as mares past the breeding stage. It is estimated that there are only about 200 breeding animals, but the information is unclear about how many of these are “pure” Newfoundland ponies.

Like many other equine breeds, the Newfoundland pony began to be bred with other ponies and even to small horses to take advantage of their desirable qualities. This, in turn, drove down the numbers of the original line. Still others were sent to the slaughter houses in Quebec, where their meat was sold to Europeans.

I recently paid a visit to Villi Poni Farm, located in Jaffery, New Hampshire, where I learned more about these animals. Villi Poni is a sanctuary dedicated to the conservation of the Newfoundland pony—not as show or ring animals, but as they were meant to be: a working companion to their human counterparts.

There are fewer than 400 “pure” Newfoundland ponies worldwide, with 40 of them being in the United States.

Emily Chetkowski, executive director of Villi Poni Farm, introduced me to these wonderful, intelligent and friendly animals. Of the 40 ponies found in the United States, 15 of them fall under the care of Villi Poni. These ponies can do everything from being ridden to pulling a plow. They are not large, only 400 to 700 pounds, but they are strong. They are cold hardy and hardworking, and Emily told me they like to work.

In the aftermath of a great catastrophe that sends our technology back 200 years, what would we do? Would we survive without the things that make our lives easier and food-gathering more efficient? We could, if we spend time now to re-learn the old, traditional ways of doing things.

In this scenario, working with the help of strong, adaptable horses and ponies is a solid start. These animals don’t use gas, need oil changes or mechanical knowhow, or run on computers—although they do need care, love and respect. If you give them that, you’ll have a much better chance of becoming self-reliant in a challenging, new world.

SOURCES

American Cream Draft Horse Association

www.ACDHA.org

American Morgan Horse Association

(802) 985-4944

www.MorganHorse.com

MerEquus Equine Rescue and Sanctuary

www.MerEquusEquine.org

Newfoundland Pony Society

www.NewfoundlandPony.com

The Livestock Conservancy

(919) 542-5704

www.LivestockConservancy.org

University of Vermont Morgan Horse Farm

www.UVM.edu

Villi Poni Farm

www.NewfoundlandPonies.org

_________Before You Buy_________

Before you rush out and pay good, hard-earned money on a horse, you need to realize what you are getting yourself into. Horses are living things, and they need care—even the heritage breeds.

Owning an endangered breed is not for everyone, because there is a great deal of responsibility beyond day-to-day care. Owning a horse (or any animal) is a lifelong commitment, so be sure you are in it for the long haul and that you have enough space and time to devote to the animal. If you want your horse to be there when you need it, you have to be there for it now.

Consider going to breed rescue sanctuaries, because they are experts on the breed and constantly work to find homes for some really great horses and ponies. While Villi Poni never sells its ponies, this organization will allow the right person to foster and/or adopt out a pony. With a little love, time and respect, you can have a great animal that can help get you through the rough times ahead.

________How to Find the Right Animal________

Some words of advice: Don’t wait until the SHTF to decide whether a horse or pony is for you. If you do, they might not be available.

Also keep in mind that a horse or pony is not the answer for everyone. It takes a special type of person to care for an animal, even an animal that can basically take care of itself. Be sure the breed is right for your area and the work you need the animal to perform, whether or not it is a heritage breed. My top three might not be what you are looking for.

Start by learning about the breeds, especially those best suited to your area. Check out The Livestock Conservancy (www.LivestockConservancy.org) and find out the basics of the heritage breeds available. Emily Chetkowski also suggested contacting the people at Equus Survival Trust (www.Equus-Survival-Trust.org). Then, contact your state’s department of agriculture, state university and other sources to help you decide the best horse or pony breed for you.

Editor’s note: A version of this article first appeared in the December, 2017 print issue of American Survival Guide.