Since the dawn of time, the cultivation and control of fire comprise one of mankind’s greatest achievements. Because of it, he was able to cook his meals and avoid food-borne parasites and bacteria; he was able to extend the day by adding light to his camp, also thereby warding off predators; and he was able to adapt to harsh winter climates by keeping warm around a fire. These benefits haven’t changed much in the last million years, because man still gathers around the fire to cook food, keep warm and light up the night.

The Fire Triangle

There are only three things you need to start a fire: a fuel source, air and heat. Without one of these elements, you’ll be cold and left in the dark. Fire is the result of a chemical reaction called “combustion.” It’s a type of oxidation—a reaction that occurs when a combustible fuel (e.g., wood or gas) is exposed to a source of heat (e.g., a match or spark) in the presence of oxygen. The oxidation of the molecules that make up fuel is an exothermic reaction, meaning it releases energy in the form of heat and light. We know the result of this reaction as fire.

Fuel

For the sake of this article, we will use wood as our source of fuel. For starters, it is abundant in nature, inexpensive in civilization (compared to liquid fuels) and easily controlled. Gathering wood for a campfire is an age-old practice, and this wooden fuel can be broken down into four main groups, each one a necessary step to easily go from spark to flame:

Tinder: Tinder is soft and light with a large surface area and easy to ignite. It is easy to imagine tinder as some combustible material that will ignite with a small spark—for example, thin wood shavings, dry grass, pine needles, cattail fluff and birch tree bark.

Kindling: Kindling usually consists of small twigs thinner than the diameter of a pencil. While tinder will burn easily, kindling is used to keep the fire going after the tinder has sparked. Consider cedar bark, dry leaves and small twigs.

Sticks: Sticks are small limbs slightly larger in diameter than your thumb (about an inch). These will maintain a small fire once the tinder and kindling have burned off.

Wood: Larger pieces of wood around 3 or 4 inches in diameter are needed to maintain a healthy and long-lasting fire.

Building a Fire

Once you start a fire, the tinder and kindling will burn up quickly, and your fire will extinguish itself if you don’t augment it with additional fuel. The process works best if you have prepared various piles of your materials before you add the match or spark to the tinder. This way, you can assemble a proper fire by using each group of fuel, gradually going up in size as you do so.

While building up the fire, make sure you don’t pile too much fuel on the fire all at once; a fire has to breathe, so leave spaces for oxygen to get into the fire. A careful balance between fuel, heat and air is essential for the fire to be efficient. Too much or not enough of one thing will snuff out the blaze.

Fire Construction

Much as a specific knife has a particular function or how specialized boots will handle different terrain, not all camp fires are equal. The purpose of the fire, whether it’s to warm, cook, provide light, last all night, signal or to be stealthy, determines the way it should be built. There are different construction arrangements—called “fire lays”—that achieve specific affects for a variety of situations.

For example, while not illustrated here, a Dakota hole fire is a small fire that sits just below the ground in order to camouflage its light. A secondary hole is dug a foot or so away with a tunnel connecting the two holes; this funnels air into the base of the fire. Also, although technically not considered a fire lay, per se, the keyhole fire utilizes rock placement to form a keyhole shape, which is perfect for cooking. While the fire blazes away in the main fire ring, a small rectangle of rocks outlines a cooking area where coals are scraped to and over which a pot is placed.

Depending on your situation, you can choose from many different fire lays. Some have very creative names, such as bean hole fire, Yukon stove and the Gilwell fire. However, most are slight variations of the nine most popular and useful designs shown here.

(Note: We used store-bought wood in our illustrations for two reasons: The consistency of each piece better illustrates the different levels and sizes of the fuel; and the construction of each fire lay is easier to recognize and describe with uniform pieces of lumber.)

Which Wood?

Collecting the right wood is essential in building an efficient fire, and while there are hundreds of types of trees around the world, not all of them make for a good source of firewood.

- Alder: Doesn’t provide a great deal of heat, because it burns quickly.

- Ash: Best-burning wood. It provides both flame and heat and will even burn when green.

- Beech: A rival to ash in heat and flame, but it does not burn well when green. It produces a great deal of embers.

- Birch: The heat is good, but it burns quickly. The smell is pleasant.

- Cedar: Burns small when dry, but it will burn for a long time. It produces crackling and popping sounds.

- Chestnut: Produces a small flame and very little heating power.

- Fir: Not a good burning wood. It makes a small flame and very little heat.

- Elder: This is a very smoky wood that burns quickly with little heat.

- Elm: To burn well, it needs to be very dry (because it contains a lot of moisture).

- Maple: This wood produces a good flame with a high heat output.

- Oak: Dry, old oak is excellent for heat; it burns slowly and steadily.

- Pine: Burns with a good flame, but the sap content causes the wood to spit.

- Poplar: A very smoky wood with low heat production.

- Spruce: Burns too quickly and with too many sparks.

- Sycamore: Burns with a good flame and moderate heat, but it needs to be well dried.

- Willow: This is a poor-burning wood, even when dry.

Ways to Ignite a Fire

Although there are many ways to start a fire (some are unintentional, such as an electrical short, a lightning strike or a chemical combination), many of the ways to intentionally start a fire without matches are mechanical and creative.

Magnification of Sunlight

- Magnifying glass

- Flashlight reflector

- Bottle or bag of water

- Polished Coke can bottom

- Convex piece of ice

- Fresnel lens

- Solar dish

Electrical

- 9-volt battery and steel wool

- Car battery and jumper cables

- Battery and fishhook

- Automobile cigarette lighter

- Lightbulb filament

Mechanical spark

- Flint and steel

- Ferrocerium rod and steel

Friction

- Fire plow

- Spindle

- Crooked stick

- Bow drill

- Rope drill

Types of Fire Lay

The long fire can be built above ground using two long logs (shown) or in a shallow trench. Either way, the effect of the logs and trench is to shade the fire from unwanted wind and to keep the coals together. The proximity of the logs depends on how large a fire you need and the diameter of your cooking pots.

This fire lay, built next to a large reflector (such as a boulder or the wall of a ravine), can be used to keep a nearby tent warm. The sticks underneath the long logs allow oxygen to reach the coals.

The rocks at either end support the main log of this fire lay. On it, various-sized kindling and sticks are laid. With tinder under the log and lots of air between the various-sized sticks, a bright and warm fire is produced.

Like a long fire, this can be used to warm a tent or keep two people on either side warm. The down side is that the fire doesn’t last if some others.

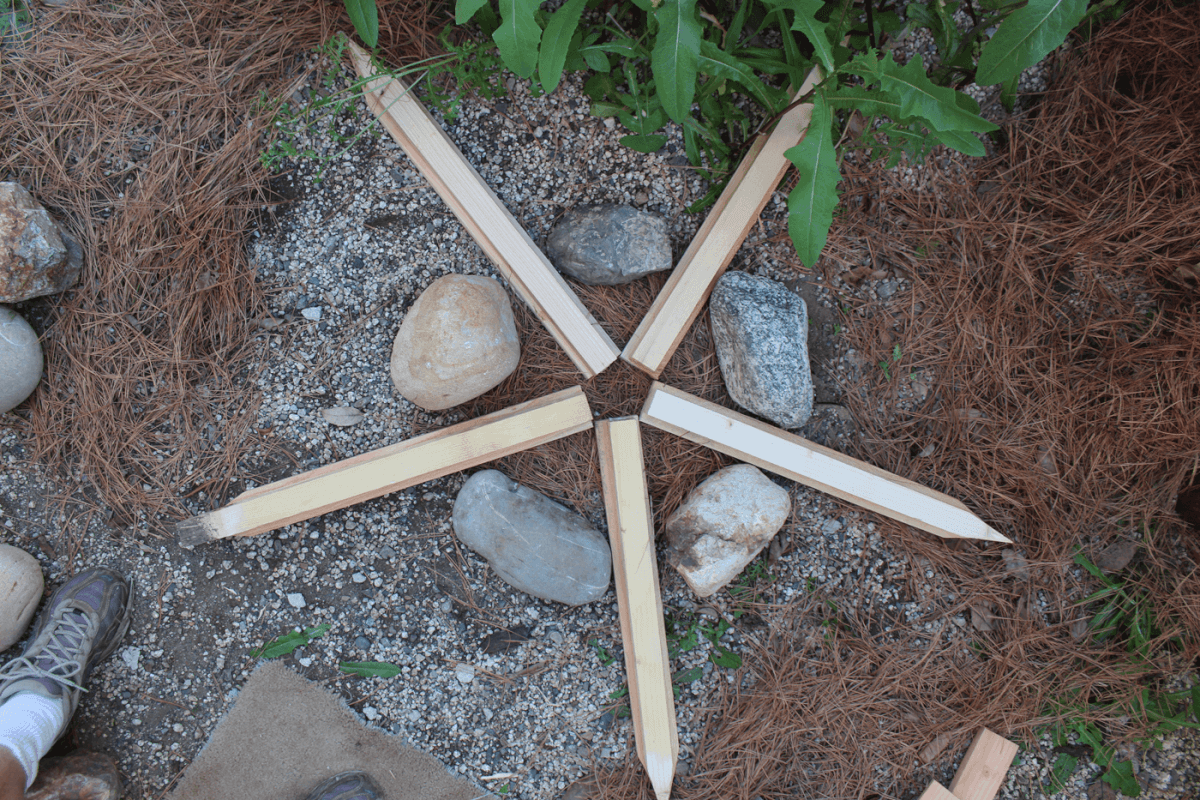

Also known as the Indian fire, this is a safe fire—one that can be easily controlled by pushing in or pulling out the arms of the star. It is also good for conserving fuel, because it produces a small fire that will burn for a long time (as long as you keep pushing in the fuel as it burns).

Because the logs of each arm can be of any length, the fire will remain the same size as long as it is burning. The stones between each arm keep the coals concentrated in the middle.

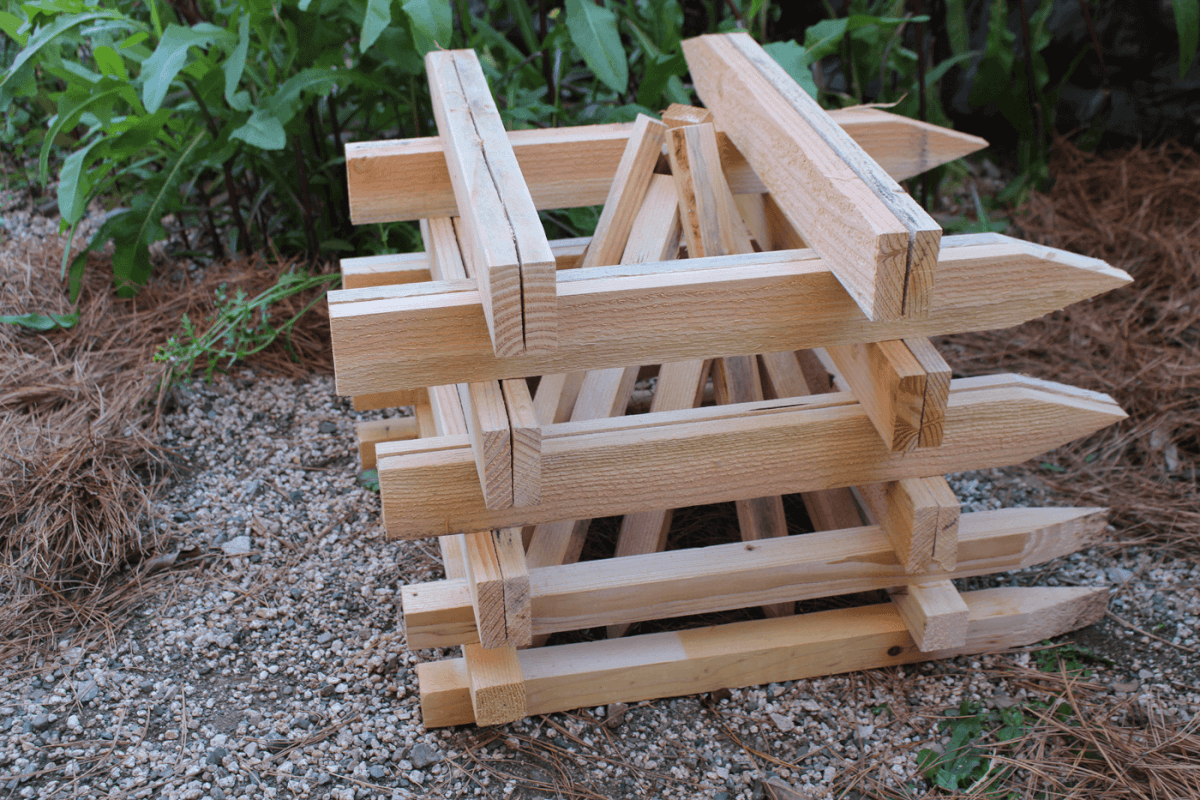

With large-sized fuel at the bottom and smaller and smaller fuel positioned as you go toward the top, the pyramid fire is a self-feeding fire. As the levels burn, it will fall in on itself, thereby adding new fuel from the upper levels as the bottom levels burn.

This is a great long-lasting fire that will keep burning, maintenance free, for hours—but it takes a great deal of fuel to build. By keeping the levels close together, you starve the fire of oxygen so it will burn slower. If done correctly, by morning, a nice bed of coals will remain.

Because of the open and airy construction of this fire lay, the log cabin fire burns fiercely, producing a great deal of light and heat. That said, it also consumes a lot of fuel quickly, reducing it to a substantial bed of coals that is great for cooking. To make the fire last longer, build a small teepee lay within the log cabin and keep it fed so the fire won’t consume the “logs” of the cabin so quickly.

The difference between this fire lay and the pyramid fire is the spacing of the fuel. With the pyramid fire, you want to limit the amount of oxygen to make the fire last longer; with the log cabin fire, the idea is to promote the flow of oxygen to have a large fire and end up with a lot of coals. The log cabin fire is the most popular fire build next to the teepee fire.

This is the most popular kind of fire lay used; it’s the one almost everyone builds when constructing a fire. It burns large, bright, hot and quickly. With the fuel angled in this manner, it creates a natural chimney that funnels a great deal of air into the spaces at the bottom, creating a very large fire.

The teepee fire lights easily and is easy to maintain (simply lay on more fuel), but the down side is that it is also a tall fire, so make sure not to construct this one under overhanging branches.

And if you toss on some green foliage for smoke, the teepee fire becomes a perfect signal fire.

Also known as a snow-base fire, the altar fire is used when the ground is particularly wet or covered in snow too deep to dig down to the ground. The idea is to build a platform that raises the fire above the snow.

By using green logs as the base, they won’t easily burn and break through to the snow below. You can create as many layers as you need to keep the fire out of the snow, but as you go up, crisscross each new layer to better protect it.

The lean-to fire is used mainly to direct the heat in a specific way: toward you. The support stick can be propped up with rocks, while larger and larger pieces of fuel are leaned up against it. The tinder and kindling are lit inside, and the fuel acts as a wind break.

This fire allows for a lot of airflow and heat, but the down side is that if the support stick is not big enough, it will quickly burn through and collapse the whole structure.

This fire lay is a slightly modified version of the long fire. The shape of the “V” via two large logs allows you to either block the wind (if it is especially harsh) or take advantage of a slight breeze to feed the fire oxygen. The V is placed either pointed toward or against the wind, depending on what result is needed.

Additionally, coals from the fire can be scraped toward the junction of the V, over which a pot can be placed for cooking. In this manner, it is a simplified keyhole fire. Adding rocks to the opening of the V can control how much oxygen gets to the base of the fire, which will determine how much fuel the fire will consume.

Ryan Lee Price is a freelance journalist who has written for numerous survival-based publications for many years.

Editor’s note: A version of this article first appeared in the July 2017 print issue of American Survival Guide.